The Into Light Project

Changing the conversation about drug addiction—one portrait at a time.

Iowa City, Iowa

This past weekend, I had the honor of speaking at a benefit concert for the Into Light Project, a national nonprofit that creates exhibitions of original portraits and individual stories of people who have died from drug addiction or poisoning.

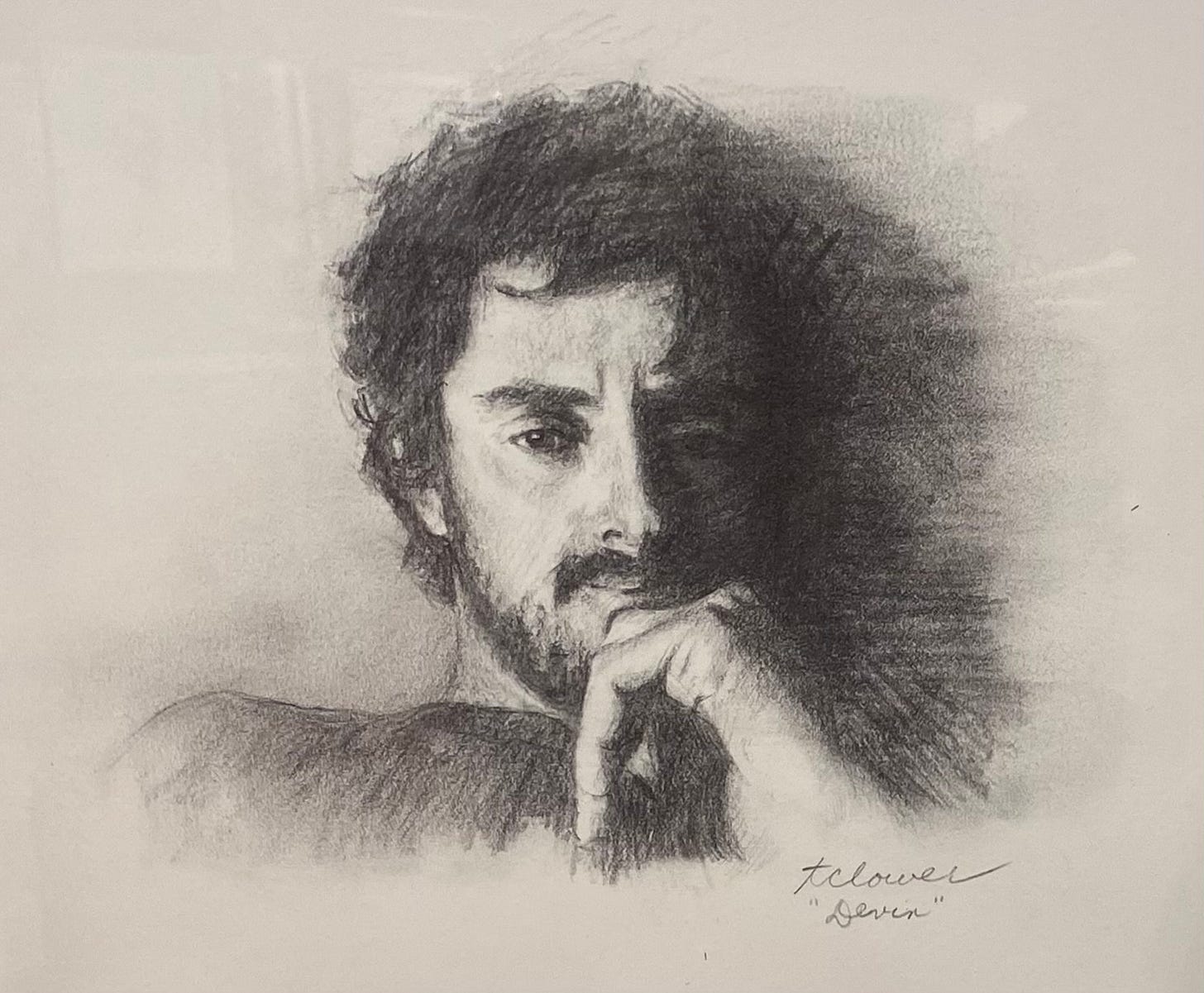

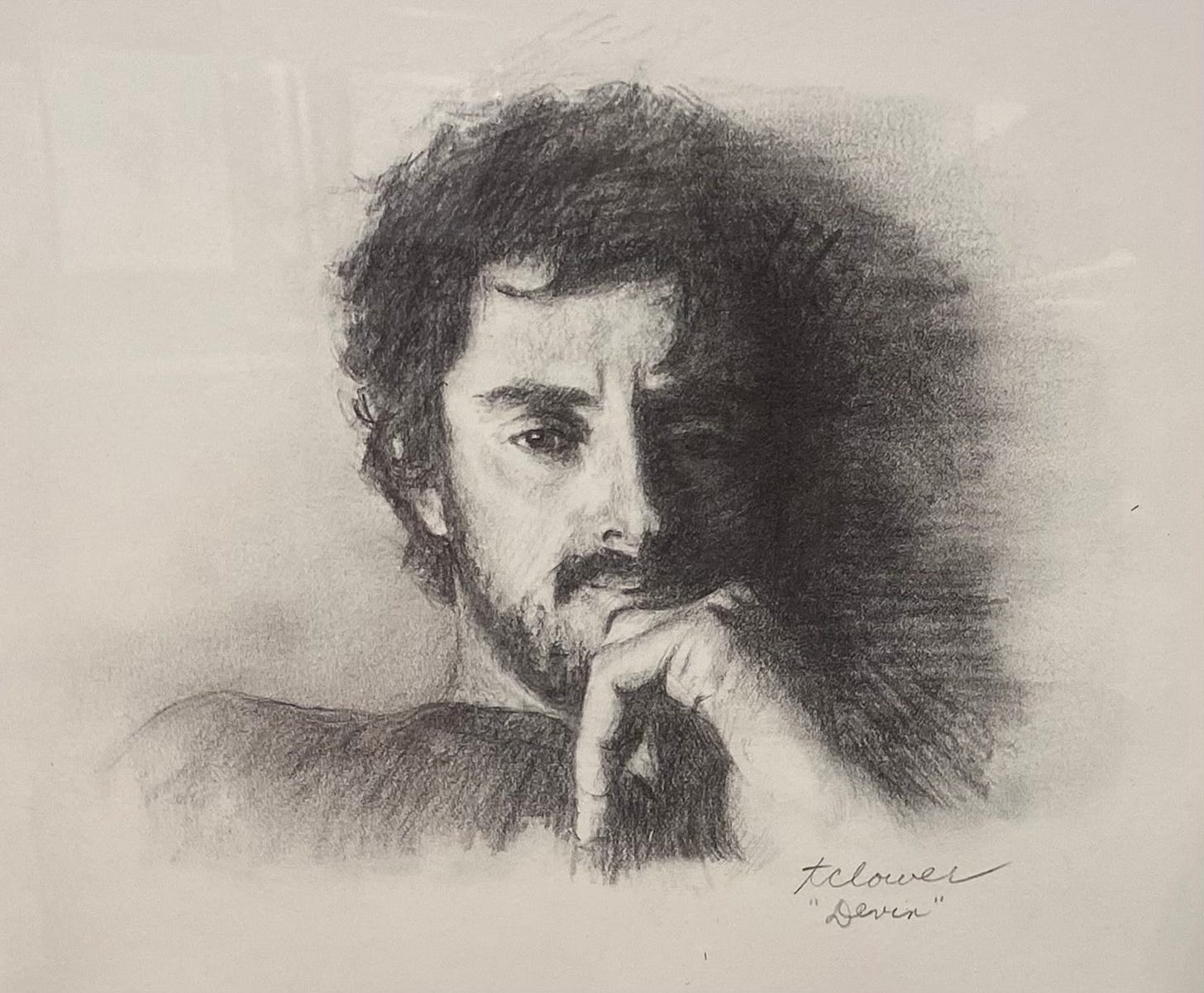

Motivated by the death of her son, Devin, from an overdose of fentanyl, founder Theresa Clower took up portrait work as a way of working through her grief. After completing Devin’s portrait, she was inspired to find others who lived and died like her son and to show the extent of the drug epidemic through exhibits involving each state. She aspired to draw their portraits, tell their stories, and start a dialogue around the disease.

And that is exactly what Into Light has done all across the country. Its mission is to bring awareness to substance use disorder as a brain disease, to erase stigma and shame, and to change the conversation about drug addiction—in other words, to drag drug addiction and substance use disorder out of the shadows and into the light.

Each exhibition, titled “Drug Addiction: Real People, Real Stories,” features up to 30 original graphite portraits of individuals from the host state who have succumbed to drug addiction, poisoning, or related causes, along with their stories. At the end of each exhibition, the family receives the portrait of their lost loved one.

The Old Capitol Museum on the University of Iowa campus was chosen as the exhibition site in Iowa, where it runs until Dec. 19. Each portrait and story was created by an artist and writer in collaboration with loved ones of the deceased. The result is an immersion in love, loss, compassion, and the overwhelming toll of substance use disorder nationwide.

The human toll is staggering, and continues: Nearly one-third of all Americans—an estimated 82.7 million adults—have lost someone they know to a fatal drug overdose. Almost 50% of those were family members or close friends. More than 321,000 U.S. children lost a parent to drug overdose from 2011 to 2021.

Mercifully, there is some good news. After decades of research, addiction is now understood to be a chronic, treatable brain disorder. Research has led to effective prevention and treatment for substance use disorders, helping millions of Americans reduce their risk of overdose and recover from addiction.

Ann Aschoff, the organizer of the Iowa City benefit, lost her son, Zachary John Aschoff, to substance use disorder in 2016. Zach was 27—a beautiful man taken far too soon. As the Iowa exhibition explains, “When Ann sees Zach’s photos and videos, she is comforted to never forget how he moved or sounded but grieves over possibly forgetting his scent or the feel of his embrace. She recalls words of a family friend following Zach’s passing: ‘Life is fragile, unpredictable, and cruel, whereas a parent’s love is unwavering and eternal. It is this stark incompatibility that sets the stage for our most devastating sufferings.’”

The miracle of Into Light is that it helps turn devastating suffering into communication, tragedy into understanding, and stigma into compassion. It was a great honor to take part in the Iowa City benefit, which featured unforgettably moving performances by Ann, my dear friend David Zollo, who graciously invited me to participate, and a host of other local artists, musicians, and writers. It was, for all in attendance and the entire community, a day of great healing, understanding, and love. Below is my small contribution. —MJ

Devin’s Story

When I first visited the Into Light Project exhibition here on the campus of the University of Iowa, it felt like I was walking into a room full of friends and family members—because that’s exactly what the beautiful faces and stories before me were, and are: friends and family members—mothers, fathers, sons, daughters—who left us too early, leaving us grieving yet still loving, hurting yet still caring, doing our best to understand and help others understand along with us.

But one portrait and story stood out—that of Devin Hart Bearden, described by his loving family as “caring, athletic, bright, witty, attractive.” Devin’s piercing, intelligent eyes reminded me of my older brother John, whom I lost when I was only 16.

I’d like to share Devin’s story with you now:

At 6’2”, Devin was lanky, handsome, and a natural athlete. Equally at home on a skateboard, snowboard, or surfing, he was a pleasure to watch—so fluid and graceful. He was a good soccer and baseball player and loved hiking in nature or being at the beach, especially on the annual family beach trips to Hatteras, North Carolina.

More than anything, Devin loved being with his family. He was full of life and brought joy and fun to every get-together. He liked clowning around and was often the center of attention. The biggest mark he made in life was the close relationship he developed with his four nieces and nephews. He would virtually become a child with them, playing endlessly. Even when it was obvious Devin was worn out, he wouldn’t say no to connecting with the kids. When asked if he ever thought about having kids, he said, “Not sure that’s going to happen.” It was as if he suspected he might not get his life together enough to do so.

As a teenager, Devin was a camp counselor for young children and later attended an experimental school in Colorado with an Outward Bound–type program. He responded well to the physical challenges and thought of being an instructor, but at twenty he was “hijacked by his opioid addiction,” his dad Joe said. “He set high standards for himself and needed to be perfect; drugs gave him the feeling of worth. He would catch a glimpse of his passion at times, but he just couldn’t find his footing.”

During Devin’s active addiction, everyone in the family rallied around him. As his dad put it, “Tough love could have been fatal love.” So, they loved him unconditionally and tried everything they could to help him overcome his substance use addiction during the 12 years it had a hold on him. “He always knew he was loved,” his mother said. Devin had just been in rehab and drug-free for 50 days; he was recovering his self-esteem and feeling good about himself. He had a date, got anxious, and went to what he knew to calm his nerves. He passed away from an accidental overdose of drugs containing fentanyl.

There is now a hole in the family that everyone is aware of, especially during family gatherings. Joe said, “It is the sadness that lingers, like a wet blanket restricting you, but then you remember the joyous times and get some relief. Devin was a good kid—we always knew that. I don’t think he always did.”

Devin died on February 4, 2018, at the age of 32.

(Devin’s father, Joe Bearden, provided the information for the above narrative, which was written by Barbara Francois. His mother, Theresa Clower, drew his portrait.)

I was drawn to Devin’s story because he reminded me of my older brother John, who took his own life at the age of 21. But Devin’s story also reminded me of the love my mother showed all three of my brothers before their deaths—each of whom was affected by mental illness to varying degrees.

Many who suffer from addiction have dual diagnoses, and science now tells us that both addiction and serious mental illnesses are brain diseases, not character flaws.

As Devin’s mother and father explained, “Tough love could have been fatal love.” So, they loved him unconditionally and tried everything they could to help him overcome his substance use addiction. “He always knew he was loved,” his mother, Theresa Clower, founder of the Into Light Project, said.

My mother, June Judge, founder of one of the first NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) chapters in the state of Iowa and a lifelong advocate for those suffering from mental illnesses and dual diagnoses, said something similar after the death of each one of her sons:

“He was loved—and he knew it.”

Love, I believe, lies at the center of compassion, hope, and recovery for all those suffering from addiction, and perhaps another diagnosis such as depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.

Devin’s mother—the reason we’re all here today—and my mother knew this to be true.

We now understand that diabetes, dementia, or Alzheimer’s aren’t character flaws; it’s high time we understand the same about addiction and serious mental illnesses.

Both Devin and my brothers “were loved—and they knew it.” It is this love and understanding that brings us all here today, and for that I am truly grateful—even as I grieve their passing and celebrate their lives.

A heartfelt thanks to my dear friend David Zollo and the amazing Ann Aschoff, organizer of this lovely event, for inviting me to speak today.

Thank you all for being here—your presence matters.

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

Good one. Strong and necessarry.

You're a good man.