What I'm Most Thankful For

Family and friends, of course. But most of all a mother who turned tragedy into compassion, fear into love, and ignorance into understanding.

Dear TFP readers,

Each year, I publish this piece in honor of my mother, on or before the third Thursday of November. Read on and you’ll understand why. Hope you enjoy it—along with family and friends gathered around a lovely table—wherever you may be.

Happy Thanksgiving,

MJ

By Michael Judge

With Thanksgiving just around the corner, I’ve been reflecting on what I’m most thankful for. First and foremost, my family and friends, who, over time, have grown together, like a tree that grafts with a neighboring tree, making both stronger. And believe me, I’m grateful for that combined strength every day of my life.

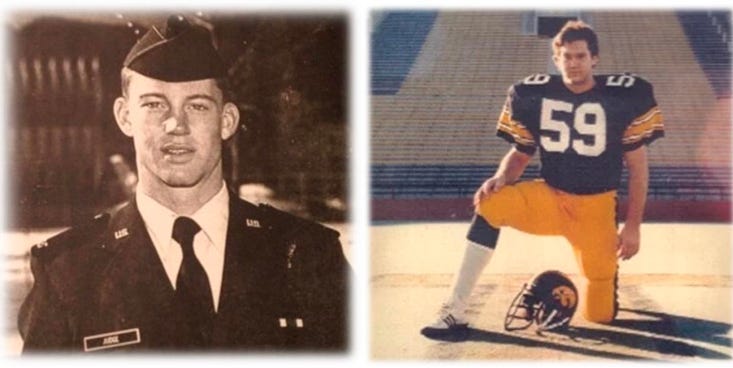

If you’re a TFP reader, you may be familiar with my family’s story. In 1979, when I was 13, my oldest brother, Steve, a dashing young Air Force Academy cadet, was diagnosed with encephalitis, and soon after, schizophrenia. It’s hard to overstate the blow this was to my family. So much promise, so much tenderness stolen away—by what? Fate? A virus? Genetics? God?

A few years later, my brother John, an NCAA Division I football player, outdoorsman, and loving father of twin daughters, was also diagnosed with schizophrenia. After battling the voices, hallucinations, and side effects from powerful antipsychotics, John took his own life in 1982, not long before his 22nd birthday.

A few months after John’s death, Steve—swallowed up by grief and an illness that tore at his very soul—stabbed himself with a steak knife in an attempt to “join his brother in heaven.” I remember when the police officer came to our house to tell us about Steve’s attempted suicide, and that, miraculously, he would have a full recovery, as the blade just missed his heart.

I’ve written about my brothers’ battles with schizophrenia many times, how Steve finally found a medication, Clozaril, that returned him to us—his gentle nature, his kind words, his loving eyes. How the family, and especially his daughters, miss John immensely. But I’ve never really written about how my family survived—the hope and love that saw us through such trying times.

That hope and love was, and still is, embodied in one person: my mother, June Judge, a fierce, loving, and tireless advocate for those suffering from mental illness for more than 40 years, indeed from the day her oldest child fell ill in 1979.

Instead of surrendering, my mother fought—the doctors, the psychiatrists, the psychologists, the social workers—anyone and everyone who said her children couldn’t be helped or were somehow not suffering from a disease of the mind as clearly as others suffered from kidney or heart disease or cancer.

She not only fought, she educated those around her, founding one of the earliest National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) groups in the nation, helping thousands get the care and treatment they deserve. She also founded one of the first Compeer programs in the state of Iowa, and taught families how to better cope with a loved one’s illness through NAMI’s invaluable Family-to-Family courses.

She even bought a food truck—lovingly named The Happy Wagon—so my brother Steve and his wonderful wife, Diane, who also suffered from schizophrenia, had meaningful work. They’d attend baseball games, parades, and county fairs throughout rural Iowa, serving chili dogs, chips, and root-beer floats, always with a smile and a sense of belonging and fulfillment only honest work can provide.

I’ll never forget the day she was called by a nearby family with a father diagnosed with schizophrenia and suffering from paranoid delusions. They asked if my mother could help. When she arrived on the scene he was on his front stoop with a rifle in his hands. He told her that if he didn’t shoot his entire family, “the world would come to an end.” The dilemma, he said, was the worst form of torture, and he thought perhaps he should just shoot himself. Somehow, with love, tenderness, and clear-eyed compassion, she got the man to put down the rifle and go peacefully to the hospital. No arrest was made, no one was harmed. And that was just one of my mother’s countless miracles.

At 88, she’s still working miracles, still giving me, my sister, Katherine, and all those who know her, the greatest gift of all—hope.

Hope despite losing three sons, a truly incomprehensible loss. My brother Steve died in 2013 of heart failure. He was 54. Yet, thanks to my mother, he had lived a full and meaningful life, “knowing he was loved,” as she likes to say. My mother lost her son John far too soon, but he, too, knew he was loved—as do his two beautiful daughters and five grandchildren. And in the spring of 2023, she lost her third son, David, who, at the age of 60, finally succumbed to decades of kidney disease.

Each one of my mother’s sons, my older brothers, knew love in its truest sense and were thankful. This, even in the darkest times, gives me hope, and for that hope I will always be thankful.

There’s a story from my childhood that I’d like to end on, a story that exemplifies my mother’s great capacity for hope, and the hope she’s given so many others.

In the summer of 1977, when my mother moved the family back to Iowa, her childhood home, from California, she put sleeping bags in the backyard so we could stare up at the night sky and see the Northern Lights. The aurora borealis was supposed to be especially bright that year, and on a clear summer night we camped out in an attempt to see the sinewy streams of blue, green and purple light filling the night sky like the smooth side of an abalone shell.

My mother, a farm girl born during the Great Depression who grew into a reluctant beauty queen, liked to do things like this. At the height of the gas crisis in the early 1970s, she took all five of us kids on a long trip from San Francisco to Vancouver, camping in the Sierra Nevadas, and farther north in the Cascades, along the way.

Our favorite place to camp was Burney Falls, about an hour northeast of Redding, Calif. There’s no major river there; the water, 100 million gallons a day, flows from a massive underground reservoir, created over a million years ago, from springs, snow-melt, and run-off from the surrounding mountains, before falling 129 feet to an emerald pool below. In the streams and forests nearby we hunted for obsidian arrowheads and watched John catch rainbow trout with ease.

When we arrived in Vancouver that summer, we took a ferry to Vancouver Island. I marveled at the size of the ferry, that we could actually drive our car onto it. Alongside the ferry I saw a pod of killer whales chasing a school of Chinook salmon. There were at least eight of them, slicing and arcing through the water at speeds of nearly 30 miles per hour—enormous, free, and terrifying.

I thought of all this that night staring up at the sky, how much my mother had shown us—how far we’d traveled together. I don’t remember seeing any unusual streams of light in the northern sky that night. What I do remember is my mother’s voice, the joy in it as she pointed toward the heavens, whispering:

“There, look there! I think I see them.”

Sending love and gratitude to you and for those who advocate for mental health.

Michael,

I was a “Junior” Bridesmaid in your mother’s wedding. Although I rarely got to Elma after that I was able to connect with June many years later. When my mother (June’s cousin) was living her last years in a nursing home, June and I had many phone conversations. She talked about times in my family I was not aware of, and filled in many holes in my brain & heart.

June is a true miracle. You are so lucky to have her as your mother.

Toni Brandmill