When in Rome . . .

A conversation with Scott Samuelson, friend, philosopher, and the author, most recently, of Rome as a Guide to the Good Life.

By Michael Judge

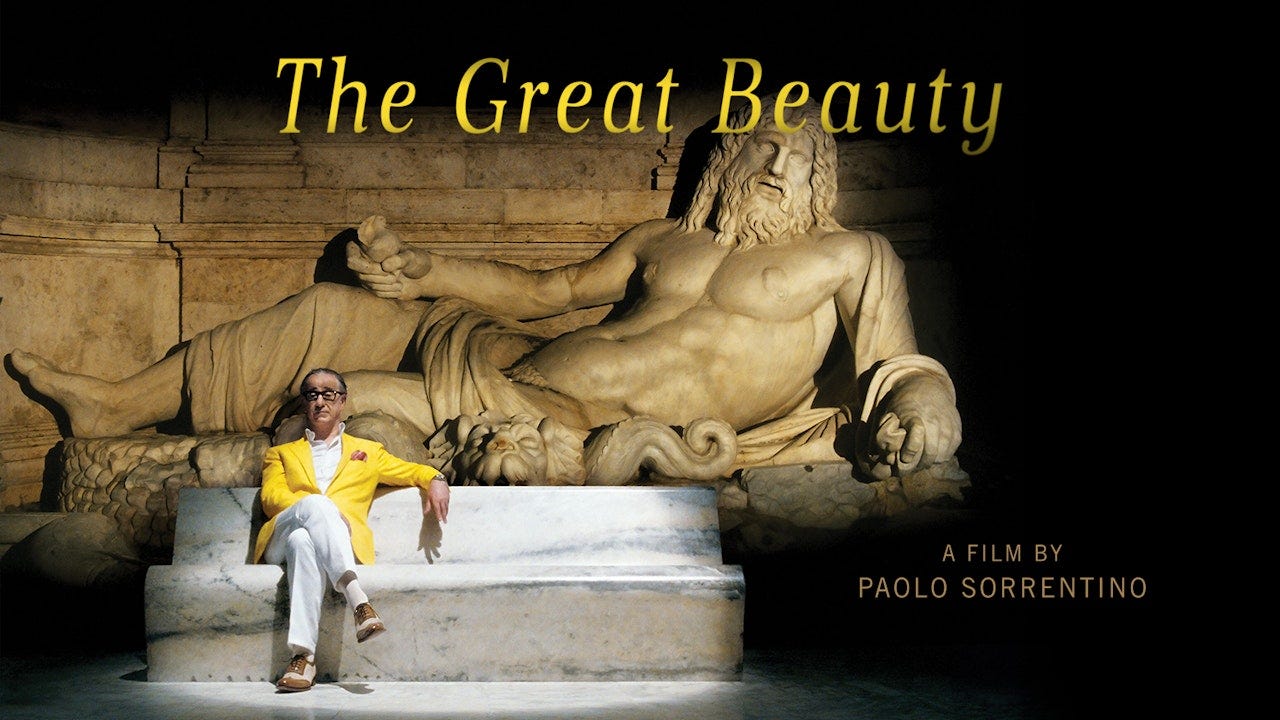

There’s a scene in Italian filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino’s 2013 masterpiece “The Great Beauty” where Jep, an aging writer who’s lost his muse, happens upon a giraffe in the heart of Rome—a real giraffe, towering above the Baths of Caracalla like Venus herself. The giraffe isn’t alone. She’s with an old friend of Jep’s, a magician who, astonishingly, makes the giraffe disappear.

The real wonder of the scene is not the giraffe disappearing, but that she appears at all—gently gazing down at Rome and Jep and us, the dumbstruck audience, before vanishing forever. In a 2014 interview, Sorrentino says the giraffe was needed to embody “the mysterious nature of those places of old Rome and the surprise that the city evokes.” Rome, he explains, “is a city where one could have the experience of seeing a magician making a giraffe disappear.”

Scott Samuelson’s latest book, Rome as a Guide to the Good Life: A Philosophical Grand Tour, is a lot like Sorrentino’s giraffe, each chapter evoking the ancient wonders and “mysterious nature” of La Grande Bellezza. Like Jep we’re left wondering—after turning the final page—how the hell he’s pulled it off. “È solo un trucco,” says the magician. “It is just a trick.” Ah, but it’s a trick—like great art, myth, faith, and love—we can’t live without.

Samuelson and I have been friends and neighbors for well over a decade, regularly meeting for drinks among the ruins of the American Midwest to better understand, if not live, at least momentarily, the good life. On this occasion we meet in his humble backyard—an eight-minute walk from mine. It’s about 85 degrees at sunset. We’re sweating slightly and sipping Negronis, 5,000 miles from Rome, awaiting the late arrival of the magician and his giraffe.

MJ: It’s funny, you recently told me your nephew Benny, a young filmmaker, began his recent interview with you with: “Rome. How do we know it even exists?” [Laughter] I love that. He’s 13, going on 30. But I sometimes feel the same way. At 56, I’ve never been to Rome, and like many magical places we’ve never traveled to, it’s sometimes easier to imagine they don’t exist. Did you feel that way before you first went to Rome?

SS: Yeah, I actually did. When I was 16, I checked a book out of the Iowa City Public Library called The Fountains of Rome, by H. V. Morton, a beautiful book. He begins with talking about what a fountain is, and I remember thinking it was a description of what art is—trying to make things play, to make the source of life come alive. I remember one of the many pictures was a picture of one of the great fountains of Rome, the Fountain of the Four Rivers by Bernini; lightning was striking behind it, and it was so cool. At that age, I thought, “What kind of city could even exist that had a thousand fountains of such beauty in it?” It seemed like it may as well have been a dream. And then I studied Latin in college and Roman philosophy in grad school. Still, until I went there in 2012, it really did feel like a dream. I can assure you; Ben is wrong: Rome does exist. And when you’re there, it actually feels better and far more beautiful than what you imagined.

Why does this Negroni taste better than all the other Negronis I’ve ever had?

Well, the traditional recipe is one part gin, one part sweet vermouth, one part Campari. I add a little more gin.

That’s the secret?

Not a lot more gin. Just a smidge more. The Italians would not like this because the Italians, especially the Romans, have the feeling that they’ve figured out how to do everything right. For instance, the Italians think it’s barbaric to order a cappuccino after 11 a.m. To them, it just makes no sense that you would ever do that kind of thing. I’m sure they think the Negroni is a perfectly constructed thing, but one’s not American for nothing . . .

That’s hilarious. As H. L. Mencken said—and I had no idea you were going to speak of the Italians’ attention to perfection— “The martini is the only American invention as perfect as a sonnet.”

Yeah, it’s true. The secret is always the gin.

But we’re here to talk about Rome as a Guide to the Good Life, not the history of cocktails. Your first two books, The Deepest Human Life and Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering, are both guides of a sort, the first to the foundations of philosophy, the second to suffering as the foundation of all that is worth living for and through. This book is more directly a guide, not just of a city, but what you call “an eclectic guide to culture and happiness, one that blends history and philosophy.” Can you speak a little about how the idea behind the book came about?

Well, it was a swirl of things. I had long been interested in Roman philosophy because the Roman philosophers were interested in how to live. They were less concerned with working out perfect theories of life and more concerned with just trying to figure out good ways of being. And I always had, as I was mentioning, fantasies of Rome. Then I go to Rome and fall in love with the city. At the same time, I am trying to be a teacher of philosophy. It’s easy to teach, let’s say, art history in Rome. You’re standing in front of the Sistine Chapel and you’re all set to talk about Michelangelo, whereas philosophy is a little more difficult. You can certainly point to the School of Athens or a statue of Marcus Aurelius and say, “Well, let me tell you about those philosophers.” But I thought, “What would it mean to be more involved in the philosophy while immersed in the city itself?” I was interested in how you do philosophy on-site.

I also thought, “When people travel, they, among other things, are seeking the good life. And maybe particularly when they travel to Italy, there’s a sense that they can be transformed.” And philosophy, too, is a kind of travel—mental travel. Plato has a famous allegory that describes philosophy as the journey out of a cave into the sunlit world. I was like, “Well, when you’re going to Rome, you’re trying to get out of the cave, and so what would it mean to do philosophy in this sunlit city that portrays our humanity like no other city?”

Part of what I love most about being in Rome is this very thing: You feel the tragedy of the ruins; you feel the beauties of the rebirths; then you feel the tragedies of the ruins of the rebirths; and then you come to feel that this is exactly what humans do over and over and over again—build on instability. The beauty of Rome is that at some point early on it started to embrace this very thing, that we are building on tragedy, that we are building on loss, that we’re building on death, and we can still be very alive even while we’re building on all of it.

Tell me a little about your mentor Donald Verene. You write lovingly about him in a passage called “Detour Through Four Pastas.” How did he influence your view of philosophy, Rome, and the good life?

I met Don Verene in graduate school. He had heard that I had read Finnegans Wake, and he was a great lover of Finnegans Wake. So he called me in and said, “I heard you’ve read Finnegans Wake,” and I said, “Well, sort of. My eyebeams have touched all the words. But I don’t know if I understand it.” He poured me a glass of sherry and told me that there was really only one way to read Finnegans Wake. “You have to go to Italy,” he said, “You have a nice lunch, and then, after your lunch, you read one page of Finnegans Wake and then take a pisolino, a little nap. It’s a dream book, and it’s meant to be absorbed through our journey.”

Sounds like most of my life.

I thought, “This guy understands things. He understands literature. He understands philosophy. He understands how to eat lunch. He understands the whole shebang!” He was my dissertation director, but we talked 10% about philosophy and 90% about food, wine, cheese. At first I thought, “Oh, we’re not talking about philosophy," but then I realized, no, we’re talking about the essence of philosophy. We’re talking about what it means to live well and to draw on the best of our traditions to empower us to live a good life. The rhythms of eating and drinking on a daily basis are at the core of what life means. He loved Rome and he loved Italy. He loved Florence even more . . .

The birthplace of the Negroni, as I’ve read.

Yeah. [Laughter] Suffice it to say, Don was and is a huge influence on me—especially his sense that self-knowledge and eating and drinking and art are all wrapped up, and that if philosophy gets away from those things, it becomes a barren, meaningless activity.

You’re leaving soon for your tenth trip to Rome with students, right?

Yes, I leave in a week or so.

Like always, you’re bringing students of all ages from a small, Midwestern community college. Some returning students, some older, some younger?

Yes. I once brought a homeless guy to Rome! But usually they’re younger undergraduate students attending community college because it’s more affordable and they’re not certain what lies ahead. Often they’re returning students who’ve served in the military or worked in the real world.

Like your first two books, this one's not a highfalutin guide to the esoteric corners of philosophy. It’s a book that speaks to—not down to—ordinary readers. Your students may be as bright or talented as Ivy Leaguers, but a lot of them have never been out of the state of Iowa, let alone the country. It must be a thrill to see Rome through their eyes.

That’s exactly right. It’s just a fact that the goods one gets out of travel are something anyone can benefit from, regardless of how much money they have.

In the book’s introduction you say you often have an experience common to travelers in Rome: a “sensation of all senses firing at once, where the body feels itself glistening like the lit-up mosaic in the Basilica of Saints Cosmas and Damian. The sunlight is clearer than usual. The terracotta buildings look like warm flesh. People’s souls are visible.” You then distill that experience into two fundamental traits: “audacity” and “self-knowledge.” Can you explain that a bit further, for an Iowa kid who’s never been?

Well, the audacity is that, in Rome, you feel like everything in human beings has been done to the max. If they deal with the issue of sex or violence or war or God or love, they do it in ways that are audacious and over the top. Most everything you see there seems to be on steroids in terms of human nature. That’s the audacity side. The self-knowledge side, to me, is about the willingness to go wherever in human nature and to try to make sense of it. Most serious cultures have histories built on violence and exploitation, but Rome shows you that from the get-go. Romans don’t try to run away from it or hide it. Almost all of us are constituted by some weird mixture of sexuality and love, body and spirit, but Rome so scrambles those things that you don’t know which is which. Interestingly, that makes you feel like you’re closer to the reality of the source of them.

You mention the magic of the Protestant cemetery. John Keats is buried there, among other “non-Catholics.” In the book you write movingly about the epitaph for Rosa Bathurst, who drowned in 1824 at the age of 16. Is that right?

Yep.

Rosa’s epitaph reads, in part, “If thou art young and lovely, build not thereon.” Could you explain what that means to you, and why you chose to name the first section of the book “Build Not Thereon”?

It occurred to me that Rome itself is, in a way, all about that very expression. Rosa was known as the “angel girl” in Rome for her grace and beauty. She was the toast of the town—a very vibrant, intelligent young woman. And then she went horseback riding and drowned in the Tiber River. It was a huge loss, and most of us can only imagine what it would mean to lose the apple of your eye who’s only 16 and full of promise. The mother who writes the epitaph, Phillida Bathurst, is essentially saying, “Youth and beauty, build not thereon.” It’s almost like she’s saying, “Life, build not thereon.” Everything we try to build on in this life is so unstable, so prone to loss and tragedy.

It dawned on me that Rome is like this too. The fundamental aspect of Rome is that it’s always building on ruins, that Rome is built on the ruins of Rome. It’s always building where, in a sense, it should not be building, or building on what has fallen before.

What it eventually meant to me, personally, was that we always have to build on tragedy. We always have to build on what we do not feel is stable. Part of what I love most about being in Rome is this very thing: You feel the tragedy of the ruins; you feel the beauties of the rebirths; then you feel the tragedies of the ruins of the rebirths; and then you come to feel that this is exactly what humans do over and over and over again—build on instability. The beauty of Rome is that at some point early on it started to embrace this very thing, that we are building on tragedy, that we are building on loss, that we’re building on death, and we can still be very alive even while we’re building on all of it.

Yeah, which reminds me of Virgil’s Aeneid. Aeneas doesn’t die on his journey, but . . .

Well, he does die on his journey. He dies far from home, but he founds a new place before he dies. In that sense, he dies at home. But it’s the home established by his journey.

That’s a good way of saying it. And doesn’t he journey into Hades too?

He does, yeah, with the golden bough.

But first he journeys out of the ruins of Troy carrying his father on his back, as we’ve talked about many times, and holding his son’s hand, he eventually founds Rome. A lot like your book on suffering, there’s a dual nature to Aeneas’s own suffering and the suffering of those of Troy. The founding of the next great civilization, the next great empire, doesn’t happen without their suffering. It strikes me now how similar Rome’s origin story is to the United States of America’s and how this country sees itself, the slaughter of Indigenous people and the slavery notwithstanding, as a beacon for those fleeing war or persecution, a “new world” out of an old order, so to speak. Do you see those similarities between the myths of Rome and America?

Civilization is not some settled people reasserting their rights. It’s unsettled people traveling and trying to come up with something new. Aeneas is fundamentally a war refugee, someone who was running from genocide, and he becomes the founder of a whole new civilization, and we’re currently living through a time where this is happening all over the world. There are people running from genocide, people running from devastation, and they are, in one sense, the most powerless people in the world, but in another sense, they contain a tremendous power of what it means to reestablish what a real polity can be. And that’s what I’ve always loved most about America.

As I mentioned, Rome faces up to its violence—the exterminations of peoples, the terrible brutality in its origins. But its deepest story is not a story of just exterminating others. It is a story of a refugee trying to make a home. And, to me, if America’s story is only about the brutality of exterminating the natives, then, yeah, we don’t have much to stand on. Indeed, that horror is part of the foundation. But there’s something else, something incredibly promising about this idea of people coming to try to establish something new. My book is explicitly about the idea of being a tourist; essentially, of someone going on a trip to Rome. But the beauty of the tourist is that you get to choose your trip. Most people in life have not been so lucky as to get to choose where they’re going. They’re compelled by circumstances to travel. They’re forced to travel, like my great-great-grandmother who was forced by her family to come here all alone from Lebanon when she was just thirteen. These journeys are sometimes the most important journeys of all.

You’re using this “guide” to Rome as a guide to something much deeper in all of us. As you say, “we build on tragedy or else we never really build at all.” And that hearkens back to what you’ve called “blues understanding” in your previous books. In this book, you say, holding up the example of Caravaggio and the genius of his paintings, that we can’t really cultivate our humanity without facing our moral and psychological ambiguities. Could you talk a little bit about what you mean by “blues understanding” and how that applies to Caravaggio and his work?

Yeah. What I talk about in the book is a great painting of Caravaggio’s where he portrays David shortly after having brought down Goliath: he’s holding the hacked-off head of Goliath by the hand and presenting it to Solomon. It’s astonishing because it is not a painting of triumph. David is looking down with tremendous compassion and almost horror at Goliath, and it turns out that the head of Goliath is a self-portrait of Caravaggio. Caravaggio painted this painting shortly after he had gotten in a fight, probably over a tennis match, and murdered someone and fled Rome. He was guilty of a capital crime. One of the punishments of a capital crime in the papal states was beheading. And so he paints this painting and sends it to Scipione Borghese, who is the nephew of the Pope in hopes that he might secure a pardon.

When I was living in Atlanta, attending Emory, I volunteered for a bit in a homeless shelter. It was run by the Episcopal church, and it was primarily for women, particularly women with kids. There was this one kid there I’ll never forget by the name of DeMarcus, about 4 or 5 years old. The first time I saw him, he was just beating the shit out of another kid, an older kid. It looked like a scene from “Reservoir Dogs.” He was just kicking the hell out of this kid. And I almost immediately gave up hope in him quite honestly. I thought, “This kid is lost.”

Turns out that he had seen his father beat his mother to a pulp and almost kill her. I soon grew to like the kid. Though he was almost totally nonverbal, I found that he liked to draw. And so we started to do drawings together, and he started to open up to me more. At one point, he drew a portrait of himself, and then he took his pencil and started just stabbing the image over and over again. And I think he was doing the same thing that Caravaggio was doing in that painting of portraying himself as this hacked-off head and . . .

And as a giant too. That painting is so striking because he’s the conquered giant, and like you’re saying, the little boy, in your memory, is a little boy who’s taking himself on, but, inside of them, they’re both giants.

Right, exactly. Powerful.

It is.

It’s an incredible thing that Caravaggio does, and it’s an incredible thing that DeMarcus was doing in his art, and that’s what I call blues understanding. Blues understanding is that ability to go to these deepest parts of our vulnerabilities and our problems and our fears and even our violence, and to be able to just be there with it. Most of us, we want to moralize it, we want to show it as “this is good” and “this is bad,” or “this is the way you should be doing it.” But blues understanding just goes to the truth of those deep things in us that are at the root of who we are personally and culturally. What it means to be human is to understand this stuff. Someone like Caravaggio, he understands it. Caravaggio was someone who suffered violence and who also inflicted violence.

Terrible violence.

And he portrayed it and got it right, and it seems quintessentially Roman what he showed. Like I said, Rome shows us again and again the violence of conquerors. It also shows us, quite profoundly, what Virgil called the lacrimae rerum, the “tears of things.”

The tears of things. Lovely. Remind me again, where exactly does the line appear?

Aeneas is on his journey to try to found what will eventually become Rome, and he is waylaid in Carthage, which will eventually become a great enemy of Rome. But, when he’s first there, he sees these images on the walls of a conquered people—of the Trojans. Remember, he is a Trojan. And he probably is, in one sense, misunderstanding the images because they’re images celebrating the triumph over the Trojans, but he says, “These Carthaginians are humane because they understand the tears of things. They understand the lacrimae rerum. Mortal things touch the mind. Mentem mortalia tangunt.” And . . .

Isn’t that a direct reference to Homer’s Odyssey, to Odysseus weeping when the poet Demodocus sings of his conquering the people of Troy?

Yeah, it probably is. But I have to say there’s something in Virgil that seems like a unique new note. Homer has the sense of understanding human suffering for sure, but Virgil has this weird new music of what it means to be traveling to a new place, and also the misunderstandings that are, in a way, deeper understandings of things. People can go to Rome and be in awe of the Roman Empire’s triumphs, but in a way—regardless of whether it’s the right reading—there’s something more powerful about understanding the tragedy of conquered peoples that the Romans themselves registered at the heart of their triumphs.

Anyway, I just don’t think you can be a human being in the fullest sense without understanding that this is part of who we are. I think that a lot of people want to run from it and wish that we were different. But humane values are built on that tragedy, on that tragic understanding, on that blues understanding.

There's a great poem by Goethe, who was a famous traveler to Italy, where he says, “A world you are, O Rome, but without love, the world is not the world and Rome is not Rome.”

I know we share a love for the film, “The Great Beauty,” by Paolo Sorrentino. In fact, I think we both count it as one the great Italian masterpieces. In a section of your book called “Dare to Be Wise,” you talk about “the trick” expressed by the film’s main character, Jep—the trick that allows us to create timeless, magical works of art that speak to us through the ages. In your book, you say, “If our tricks aren’t up to the tasks of loving and dying, if our stories don’t gather up the great beauty, we’re stuck with hypocritical religion, corrupt politics, stupid entertainment, pompous art, and endless distractions.”

So, my friend, what’s the trick?

Good question! If you get the DVD of the Great Beauty, there’s an extra scene that’s not in the movie itself. Jep, who’s about to turn 60 and has lost himself in the dolce vita of Rome, wrote a great novel when he was young. But he’s become a journalist and distracted himself from literature for a long time. So, in the scene, he’s interviewing this great Federico Fellini-like movie director. And the director says something like, “I feel like I haven’t done anything important.” And Jep says, “What are you talking about? You’ve made all these films that have shaped millions of people’s imaginations.” He replies, “No, I want to make a film that really awakens people and their imaginations.”

Jep is all ears. And the old filmmaker says, “I have this idea of a movie that I make about a beautiful young woman whose eyes change colors every time she blinks. She blinks her eyes and they’re blue or brown or black or red.” And he says, “It goes back to when I was a young kid and my parents took me to see the first traffic light in our city. There weren’t any cars, but everyone just stood around and marveled at seeing this traffic light change from red to yellow to green and back again.” And he says, “Que bellezza, que grande bellezza!” What beauty, what great beauty!

And that’s the trick, I guess. Things really do appear to be a great beauty when we see them in the right light. I think of our pal, the great musician and teacher John Rapson, who died not that long ago, and he knew he was going to die. He had cancer and he saw so many things as the great beauty. Just seeing a friend, just seeing life around him was the great beauty. A traffic light is just a traffic light. But it is also the great beauty if you see it in the right way, if it’s a girl whose eyes change color when she blinks. The trick is to figure out that way of seeing something so that it becomes the great beauty to you, so you see what’s astonishing about it. Jep has to do that with his own life and with Rome itself. And he does. By the end of the film he does see and appreciate the great beauty again, but first he has to reconnect with the things that are beautiful and tragic in life as well as reconnect with his first love. So I don’t know if I have the trick all down, but it does seem to me the trick is to see things as if for the first time, even if you’ve seen them a million times before, to feel them in their undiminished great beauty.

Well, it goes back to the beginning of the book when you talk about that feeling, when your body is tingling and it’s an epiphany in sort of the truest sense. It’s not a literary epiphany. It’s a physical epiphany in the real world, in this case Rome, when “the body feels itself glisten.”

Exactly. When art forgets that, it becomes a bit of a pointless thing. When politics forgets the great beauty, it’s just a power play. But when what we do remembers that great beauty . . . it seems like the best stuff we’ve got.

“The only thing better than falling in love with Rome,” you write, “is falling in love in Rome.” You’re one of the lucky few, I suppose, millions upon millions actually, that have experienced both.

Yeah.

So how did that feel?

Good!

Let me rephrase that. So you’re in the "eternal city," this palimpsest of culture, ruin, culture, ruin, culture, ruin, etc. But you experience this eternal emotion in the middle of all of that—romantic love—that is you experience a new beginning, a rebirth, of sorts. That also must have been a source of inspiration for this book.

There's a great poem by Goethe, who was a famous traveler to Italy, where he says, “A world you are, O Rome, but without love, the world is not the world and Rome is not Rome.”

Damn.

He says in another poem something along the lines of, “I couldn’t really understand the marbles of Rome until I counted out the meters of my poems on the back of my Italian lover.”

That’s beautiful.

And it’s the truth: You can’t fully understand the eternal things without touching the fleshy things.

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE