This Writer’s Life, Part Two

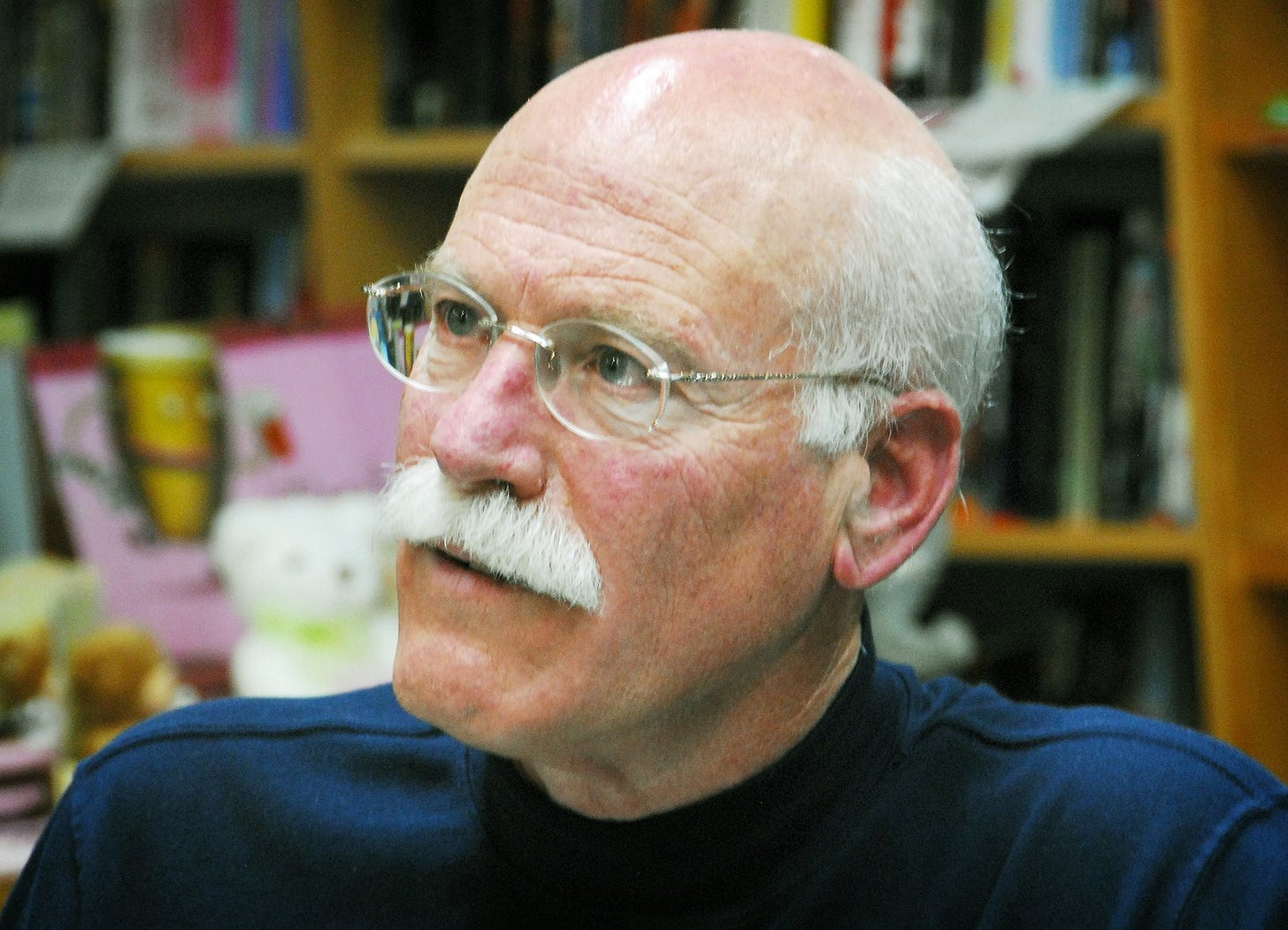

A conversation with writer Tobias Wolff about war, family, memoir, and the ethics of storytelling.

By Michael Judge

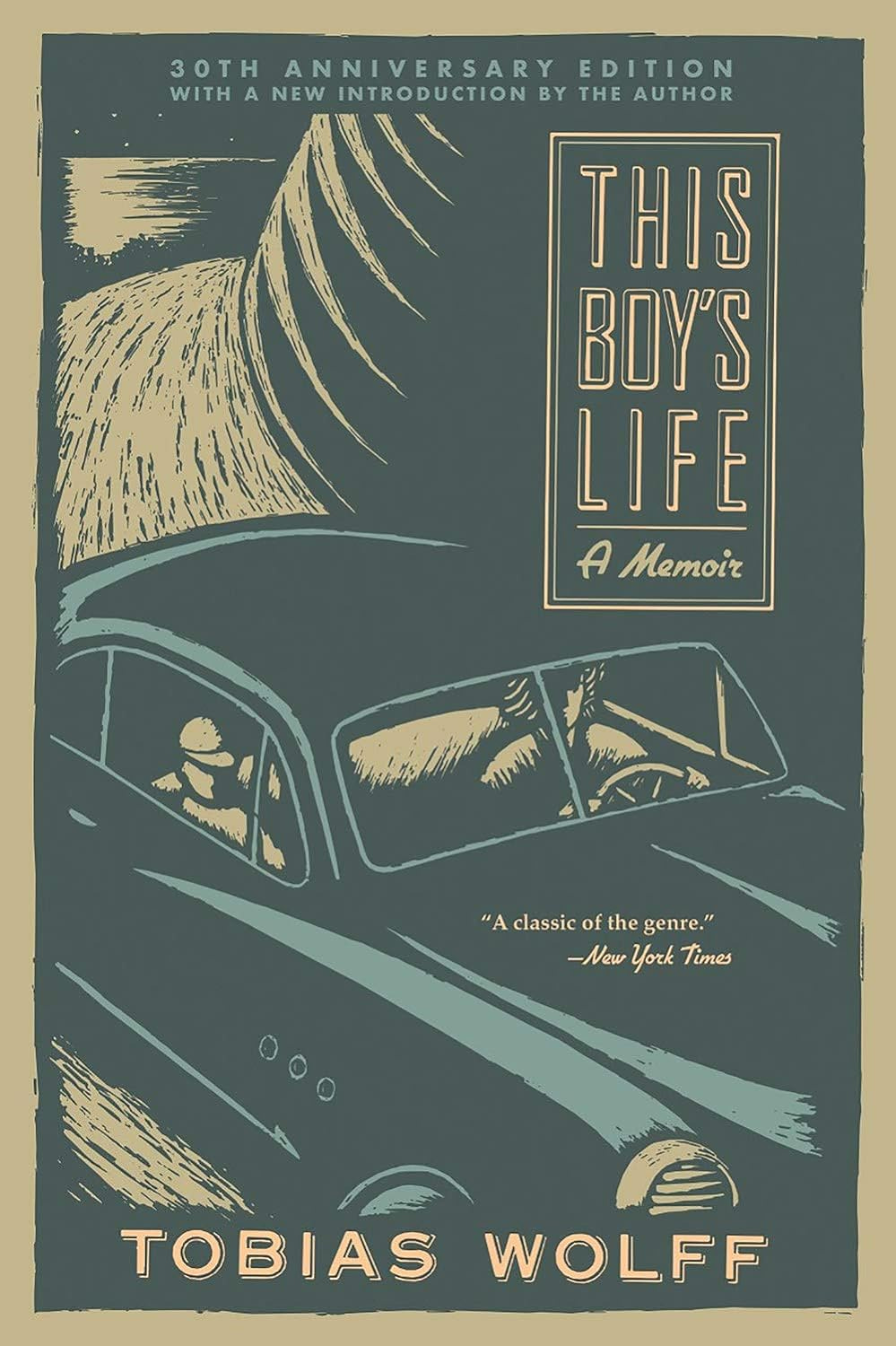

Last week, in Part One of my conversation with Tobias Wolff, author of the acclaimed memoirs This Boy’s Life and In Pharaoh’s Army, we discussed the art of memoir writing and, in Wolff’s words, how the writer must “practice a kind of restraint and not artificially cushion” the person they were in the past. Why? “Because they were on their own then. They didn’t have you looking over them and seeing how things were going to end up later. So you have to preserve in some way the—how can I put it?—the independence of that young person you’re writing about or younger person from your present self.” It’s that kind of insight that has earned Wolff numerous awards, including the National Medal of Arts, the highest honor the U.S. government can bestow upon an artist. Wolff received the award from President Barack Obama in 2015 “for his contributions as an author and educator” and his examination of “themes of American identity and individual morality.” “With wit and compassion,” the National Council on the Arts explained, “Mr. Wolff’s work reflects the truths of our human experience.” That wit and compassion isn’t just on display in his work, but in the classroom where he teaches creative writing at Stanford University, and indeed in the conversation that continues below, for which I am eternally grateful. Part One ended with us discussing how a writer reflecting on his or her own past must, in Wolff’s words, “find some way of keeping those realms distinct,” for they—like all of us—are no longer the person they once were. —MJ

MJ: I guess Heraclitus was right: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.” My old teacher, the poet James Galvin, who wrote a beautiful memoir called The Meadow . . .

TW: I love that book.

It’s extremely lyrical and at the same time brutally honest. But Jim says in one of his poems, “You can’t step into the same river even once.”

That’s good, isn’t it?

Yep. Galvin’s got this sort of mystical sense of nature and man’s relationship to it and it’s absolutely true. I’ve found that when I’m trying to write memoir, my biggest pitfall is the present tense, which I try to avoid now. By putting it in the present tense, much like a poem, I wasn’t protecting that child from a distance, I was becoming that child again, and that wasn’t good for the writing. Like you, I had kind of an erratic upbringing in some respects. My mother divorced my father and we drove from the Bay Area to Iowa in 1977 in a tiny Datsun, my 16-year-old brother John driving the U-Haul full of our belongings. A few years later all hell broke loose when my oldest brother, Steve, a cadet in the Air Force Academy, and then John, a football star, were both diagnosed with schizophrenia. Anyway, I found that by going into the present tense, I was too present in those experiences. I’m now putting it fully in the past tense, which helps me look at that child or that younger person with the experience that I have now. Does that make sense to you?

Yes it does. It gives you the longer view, definitely.

“You’re not alone in this world. Your life touches other people’s lives and you have to recognize that without necessarily being inhibited by it. And that’s always the problem with writing a memoir. Your life . . . this account you’re making of a life, is actually an account of other lives too, and you’re making or suggesting judgments about other people’s characters. At some level you have to eventually say, “Yeah, I’m doing that, but I can’t let that put a muzzle on me. The knowledge that I am doing that cannot shut me up.”

I think there’s a kind of romanticism to that sort of Holden Caulfield voice that is extremely difficult to pull off, especially if it’s not a novel or a novella or something like that. But I also get that sense in In Pharaoh’s Army of you looking back on your life, long after the war in Vietnam, and your sense of responsibility to the story but also to the right tone. There’s this great line when you say—I think this is when you’re with your girlfriend, Jan, and Dicky and Sleepy, two enlisted men you served with, in a bar shortly after you’ve returned home . . .

Oh, those guys at the end, right?

Yeah. You’re telling a story about an ill-advised Chinook helicopter landing, how the storm from its blades blew away the locals' homes and lives, and you're trying to find the right tone for the occasion, and you say: “How do you tell such a terrible story? Maybe such a story shouldn’t be told at all. Yet finally it will be told. But as soon as you open your mouth you have problems. Problems of recollection, problems of tone, ethical problems.”

That’s right.

What do you mean by “ethical problems”?

Well, it’s a story of that kind in particular, but really I would say this would be true of any memoir. It’s not only your own character and experience that are implicated in the story you’re telling. They impinge on other people’s lives too. They draw on other people’s lives and experience. For example, with the whole episode with calling that damned helicopter down rather thoughtlessly into where the gale of the blades would cause damage, just not thinking. You could make a comical scene out of it but that would ignore the actual experience of the people who lived in these places whose roofs were being blown all over creation and whose illusion of safety and security was being suddenly shattered.

So your story is touching other lives and it can do so in—how can I put it?—in a careless and consequential way. You’re not alone in this world. Your life touches other people’s lives and you have to recognize that without necessarily being inhibited by it. And that’s always the problem with writing a memoir. Your life . . . this account you’re making of a life, is actually an account of other lives too, and you’re making or suggesting judgments about other people’s characters. At some level you have to eventually say, “Yeah, I’m doing that, but I can’t let that put a muzzle on me. The knowledge that I am doing that cannot shut me up.” But you take that on when you write a memoir. You’re going to be stepping on other people’s lives.

There’s a passage in the book where, after the war, you come across a line in George Orwell’s essay “How the Poor Die” that infuriates you. “Orwell had me in the palm of his hand,” you write, “till I came to this line: ‘It is a great thing to die in your own boots.’ It stopped me cold. Figure of speech or not, he meant it, and anyway the words could not be separated from their martial beat and the rhetoric that promotes dying young as some kind of a good deal. They affected me like an insult. I was so angry I had to get up and walk it off. Later I looked up the date of the essay and found that Orwell had written it before Spain and World War II, before he’d had a chance to see what dying in your boots actually means. (The truth is, many of those who ‘die in their boots’ are literally blown right out of them.) Several men I knew were killed in Vietnam. Most of them I didn’t know well, and haven’t thought much about since. But my friend Hugh Pierce was a different case. We were very close and would have gone on being close, as I am with my other good friends from those years. He would have been one of them, another godfather for my children, another big-hearted man for them to admire and stay up late listening to. An old friend, someone I couldn’t fool, who would hold me to the best dreams of my youth as I would hold him to his.”

It’s a figure of speech Orwell was using and I probably came down on it a little hard, but it did affect me when I read it. I thought, “Oh, you don’t know what that means.” And he didn’t actually know what it meant, but he came to find out. I love Orwell though. I’m loath to criticize him about anything. And I love the essay that that comes from, or the recollection that that comes from.

In your email to me on Memorial Day [see here], you were kind enough to write about Hugh’s death and the Wilfred Owen poem, “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young.” And in the book, there’s a beautiful line about how someone dies in your stead, I mean literally in your stead. This is a little close to the bone, but when it came to In Pharaoh’s Army, did you feel you had to tell these stories because you’re alive in Hugh and other men’s stead, and at the same time had to get it right?

That’s right. You owe them that. I mean, in deciding to write about that experience at all, I did think that I owed it to the man that I call Hugh in the memoir and others that I knew to be as truthful as I could be to get it right. Not dramatize it or melodramatize it. Just to try to get the feeling of the experience really down truthfully. I didn’t want it to become a kind of screed, a denunciation of the war. And in fact, a couple colleagues of mine criticized me for it. “Why don’t you come to a clearer conclusion about the folly of the war?” and all that. And it just seemed to me we didn’t have the luxury at the time of thinking that way. We might have had our suspicions, but that wasn’t part of our experience except in the soldierly conversations and banter about the idiots, the higher ups, that kind of thing.

So I really wanted to—how can I put it?—I wanted to keep it true to the experience that we actually had there and that is the best way that I could think of honoring [the man I call Hugh in the book]. I’m going to call him by his real name now, in our conversation, but please edit that out. I mean, I can’t keep calling him a pseudonym. He was my best friend at the time . . .

Right.

He was such a wonderful guy.

Well, I’m honored that you felt comfortable enough to share his name with me and how you felt about him. And the poem that you . . .

It’s so strange. I still feel a kind of absence in my life with him not in it. I’m very close to friends that I was . . . You know, my best friend in the world I’ve been best friends with since we were 16. I’m his daughter’s godfather. He’s my daughter’s godfather. We see each other whenever we can. I have another friend that I’ve been friends with who I’m still very close to, since we were in high school in Concrete together, and we email a lot. Those connections have abided for me. So when one got broken in such a way, it just never really healed.

I wasn’t familiar with “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young” until you quoted it in your email. Most people are familiar with Owen’s poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” or “Anthem for Doomed Youth” but…

“What passing-bells for those who die as cattle?” right? And “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est / Pro patria mori.” But God, I love that Abraham and Isaac poem.

God ordered Abraham to sacrifice his son and a ram appears and is slaughtered in Isaac’s stead, right? That’s the biblical story. But in Owen’s poem, tragically, that’s not the case.

Right.

Owen writes:

. . . Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him. Behold,

A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns;

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.

Exactly. I have to say, looking back on it, it isn’t something I wanted to make much of in the memoir because I had a different project in mind than, as I said, writing a screed. But I think of the pride that kept that folly going for so long. People just unwilling to admit that it was a folly and a mistake and just pouring more into it, more people into it, more . . .

Well, I want to say once again, I’m sorry for your loss and the loss of your friend.

Thank you. I appreciate that.

We’ll wrap up soon. But I wanted to say that one of the things I most admire in your work, your memoirs especially, is there’s not a trace of self-pity.

Honestly, I just feel like I’ve been so much more lucky than unlucky, that I’ve had so many breaks as opposed to bad breaks. That I’ve enjoyed such friendships and very few enmities. I don’t have a lot to feel sorry for myself about, to tell you the truth. I mean, I had certainly a bumpy youth in some ways, but I also had a great mother. And boy, you have a parent like that, they really carry you.

Right. I’m glad you mentioned your mother. I think especially in This Boy’s Life, there’s a sense of adventure and not an inkling of self-pity. That sense of adventure, it seems, came from your mother. My mother was the same way. She’s brave. The bravest person I know. And I think part of that was getting in that little Datsun and driving all the way from California to Iowa. She kept telling us that we were going to see the Northern Lights when we got to Iowa. And Iowa’s pretty darn far away from the Northern Lights, right? But one night she put sleeping bags in the backyard and we all fell asleep waiting to see the Northern Lights, and it was just beautiful. I feel like I had a wonderful childhood even for all the pain that accompanied it.

I know exactly what you mean.

I’m so grateful we were able to have this conversation.

Well I’m glad we were able to as well.

At the risk of sounding very corny, you remind me of the man my older brother Steve might have been had he not been stricken with schizophrenia.

I’m honored.

Your writing—your voice, tone, and refusal to descend into irony or bitterness—is a real triumph, and I see it as a model.

Thank you, Michael. I hope we’ll talk again someday.

A wonderful interview with a great man. Insightful, hopeful, inspirational, especially to a memoirist; and to anyone thinking of writing a memoir.