The Value of a Coach

With just two words, "I know," Coach Lenius allowed me to surrender; he eased my rage and allowed me to grieve.

By Michael Judge

With high-school and college football kicking off in full force this weekend, I’ve been thinking about my “glory days” on the gridiron, short-lived as they were.

You might not (or might) know it to look at me, but 40 years ago this summer I played my last football game. It was the summer of 1985. Reagan was president, rockstars at Live Aid were trying to save lives in Africa, and the No. 1 song was “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” I know we lost, and that I—a scrappy linebacker without the size or speed to play at the next level—didn’t play well. We lost. I think by one point.

I don’t remember the exact score, but I do remember a few ticks on the game clock I wish I had back. It was a play-action pass, and before I read it the slotback had snuck in behind me and caught a wobbly touchdown pass that passed just over my head and out of reach. Good grief. It’s all coming back to me now, in slow-motion, no less. But lucky for me it wasn’t a real game, more an unfriendly exhibition.

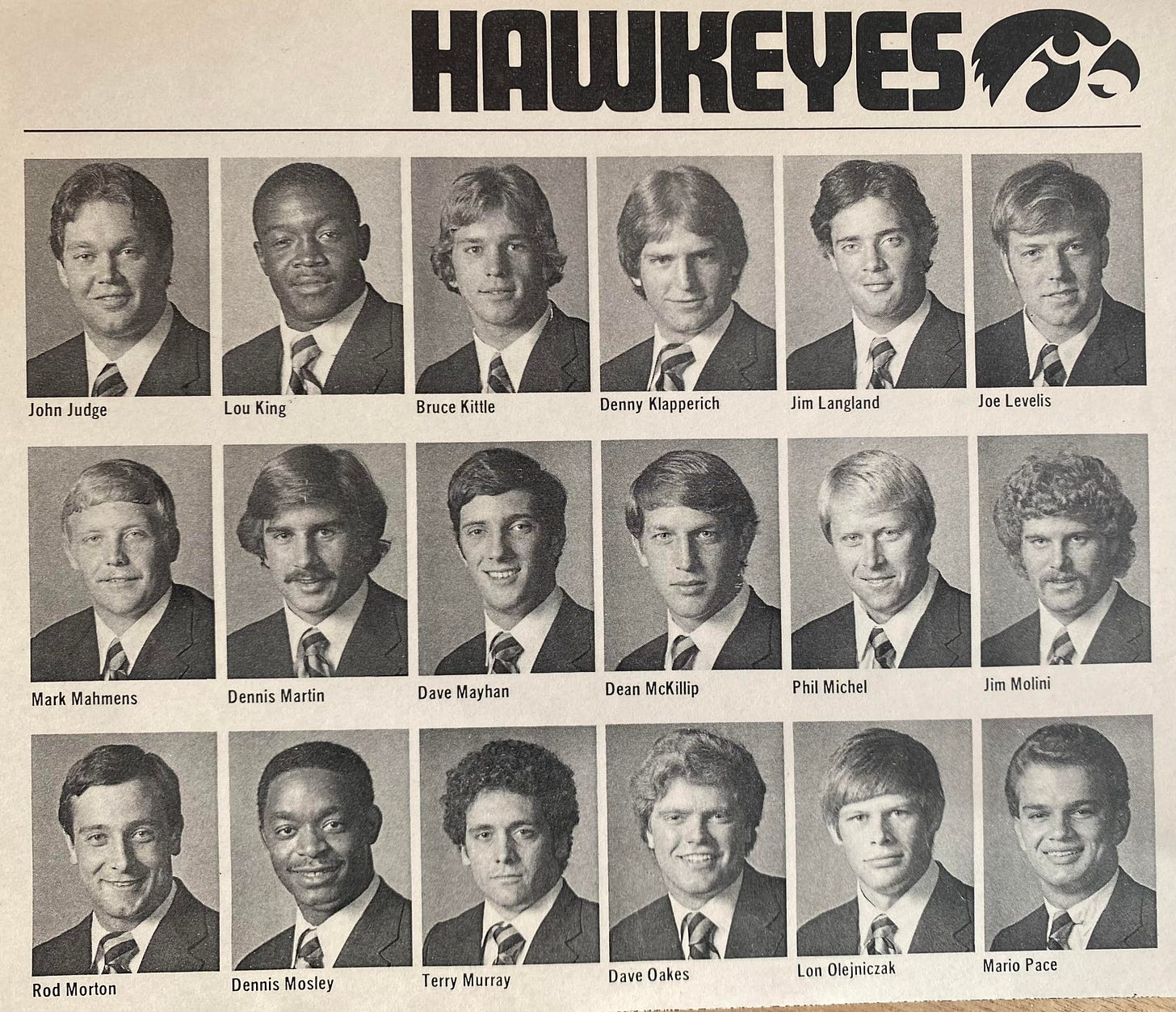

It was the Iowa Shrine Bowl, an all-star football game between North and South recognizing senior athletes and coaches. I’d already decided I was done with football, so the event was a kind of ceremonial farewell to a game that I had played with all my heart for five formative years. I’ve said it before, but football—the training, the guidance, the discipline, the camaraderie—perhaps more than anything else helped me survive high school and the death of my older brother John—an all-state defensive lineman who’d played at the next level for Hayden Fry’s Iowa Hawkeyes—at the start of my sophomore year.

John had suffered a terrifying and debilitating psychotic break at the age of 20, was diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia, and took his own life just before his 22nd birthday. Every game I played, I played for John, who once told me his secret to football success: “Most players give 100% a few times, then slack off. The great player never slacks off, never loses concentration. The great player gives 100% 100% of the time.”

But let’s back up a bit. My last real football game was on Nov. 2, 1984, against the East Waterloo Trojans, at historic Sloane Wallace Stadium, home to both the East and West Waterloo high-school football teams until 1994. I remember the score of that game, but won’t tell you.

I also remember, in the last few minutes of a losing battle, refusing to leave the field—not even to give our capable underclassmen some valuable playing time; not on your life. I’d never stood on the sidelines and wasn’t about to be standing there when the clock ran out.

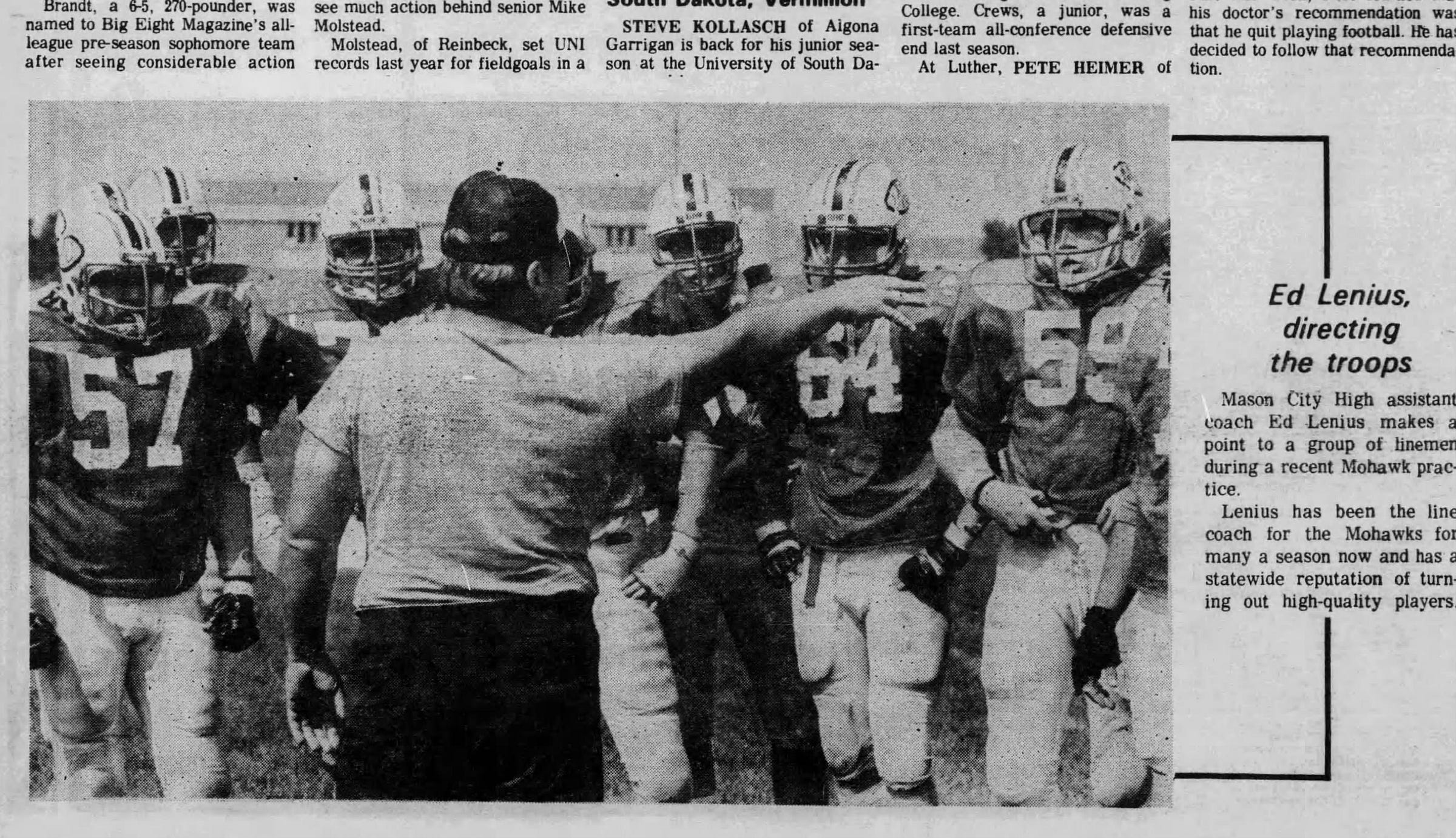

But what I remember most is what happened after the game—and the coach who reached out and gave, again and again, that heartbroken Iowa kid the faith and strength to continue, not just on the gridiron but in life. His name was Ed Lenius, better known as Coach Lenius—or just plain “Coach”—to the many hundreds of offensive and defensive linemen he taught, cajoled, and mentored in a teaching career that spanned nearly four decades when he retired in 1998.

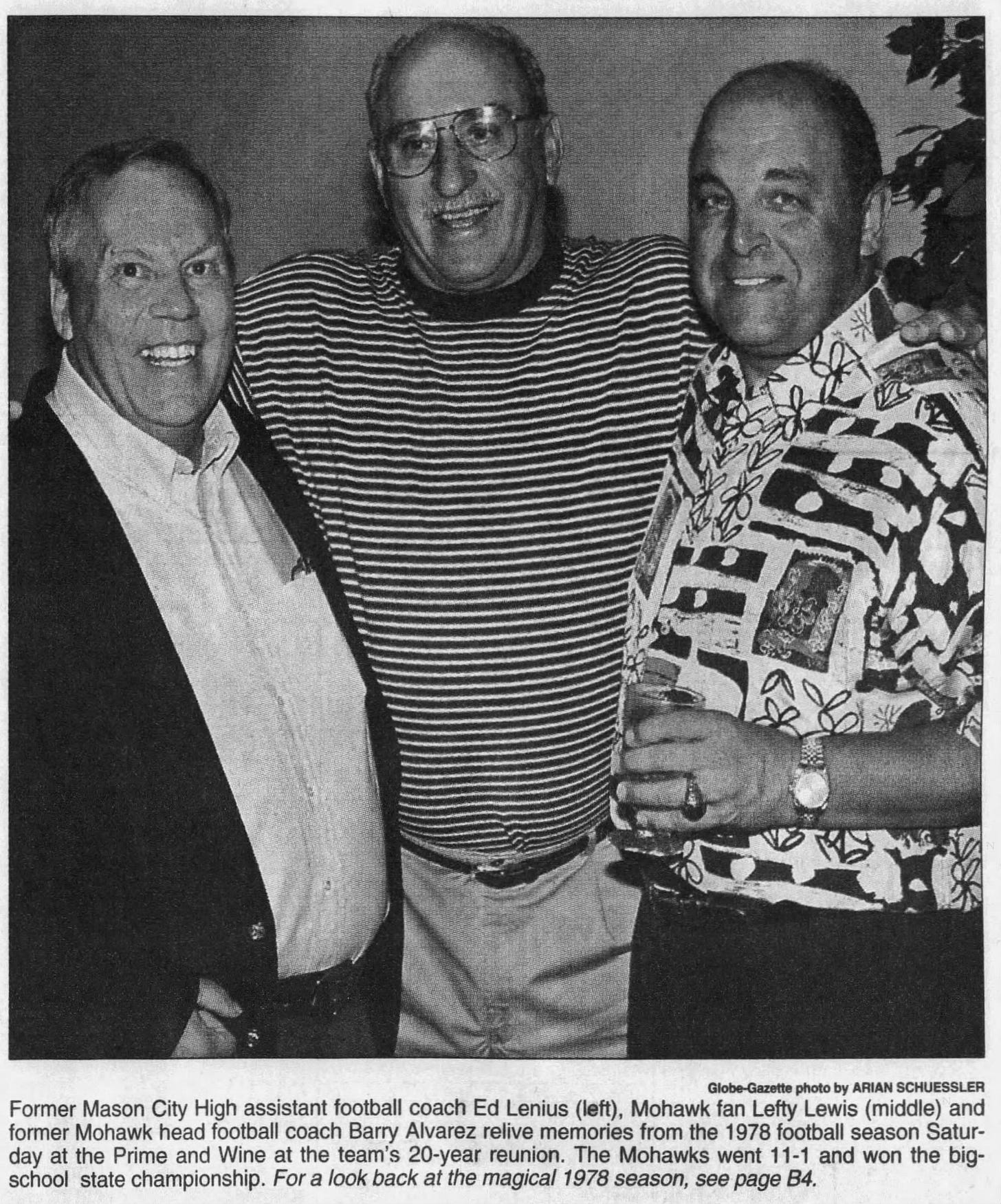

Coach Lenius taught business courses when he wasn’t on the gridiron. His accounting class was famously tough, even for bookworms, but he made it accessible and rewarding, even for noseguards. Everyone knew that he and coaching legend Barry Alvarez (later a Rose Bowl champion and celebrated head coach at the University of Wisconsin) had taken the Mason City Mohawks to the 1978 state tournament and returned home with the championship trophy.

I’ll never forget that cold November night in Northern Iowa. The whole town parked their cars along Highway 18, shining their headlights toward the centerline, lighting the way home for their returning sons, who were now—truly and indisputably—champions. I still get shivers now, pushing 60 and four decades away from the smell of the grass beneath my feet, and still more from that glorious night, when Mason City wasn’t just a tough town with cement plants and decent wrestlers, but a city of champions. My brother was on that team, and even though his life was cut short by a devastating brain disease, it was full of joy and greatness and wonder and celebration, perhaps—aside from the birth of his twin daughters—most of all that night.

Which brings us back to that night at Sloane Wallace Stadium in East Waterloo and my final game of football. I’d walked off the field that night with my head held high, as Coach Lenius (and my brother) had always taught me. But when I entered the darkness of the locker room—after the handshakes, far from the lights—I felt a sense of tremendous loss, as if this final game, this final effort, was the undoing of a sacred bond I had with my brother John, as if my silent prayer to him before each kick-off to give “100% 100% of the time” had been for naught.

I was sitting on a wooden bench staring at nothing when Coach Lenius came into the locker room—a stocky Irishman with a wild grin and a way with words that made you believe you could do anything—and our eyes met.

“I know, babe,” he said. “I know,” putting his hand behind my neck and pulling my forehead to his.

“I know.”

And that’s all it took. He allowed me to surrender. The battle was over. Like King Priam’s embrace of Achilles after the slaughter of his son, he eased my rage and allowed me to grieve.

“I let him down,” I said, between sobs.

“No you didn’t,” Coach Lenius said. “No you didn’t. He’s proud of you, and always will be.”

I’ve carried those words with me. And I believe they’ve helped me to move on from football to other pursuits perhaps more suited for a skinny (at least back then) and slow (to this day) Midwestern kid who prefers indoor sports like darts, pool, and bullshitting more than the outdoor ones.

I’ve returned a few times to Mason City in the past 40 years, once in 2008 to see Coach Lenius, attend a lecture by Coach Alvarez, and celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Mohawks’ 1978 state championship. He was seated in a wheelchair surrounded by others when he saw me. His eyes lit up. And he put out his hands, gesturing for me to come forward. The next I knew he’d pulled me down to his level, his hand cradling the back of my neck, just like in East Waterloo after that final game.

“Two words,” he said. “Sloane Wallace.”

I don’t remember much of what Coach Alvarez said that night. But those two words meant everything to me, and that feeling of surrender, forgiveness, and understanding came flooding back.

Coach Lenius—Edsel L. “Ed” Lenius—died July 28, 2019, of natural causes while visiting his son, Todd, in Georgia. I played football with Todd (appropriately for a Lenius, he played monsterback) and he greeted me at the funeral with the same wild grin his dad always greeted me with. “Hey, Judge. I’m glad you could make it,” he said, clasping my hand like we’d just made a stop on fourth and short.

Missy Layfield, a beloved trainer for the Mohawks for decades and later a newspaper editor, wrote a beautiful tribute after Coach Lenius passed, explaining how much he loved the “big uglies” and “babes” he coached. “They were big kids,” she wrote in an editorial titled The Value of a Coach. “None of them were going to sprint 60 yards for a touchdown. Most were average kids from solid families, but some had trouble at home, or worse, apathy. And, this being high school, high self-esteem was rare in this bunch. These are the boys he chose as his own, often recruiting in his business ed classes or in the hallway.”

Coach Lenius, she continued, “taught them all he knew about blocking, tackling and life. How to go up against an opponent that seemed invincible. How to hold your head up when you lost. How to focus on the next challenge. How to be a good winner. How to be part of a team and support each other. Life lessons that athletes often don't realize are life lessons until they're long past high school.

“I've seen it. The smile of a chunky lineman lighting up the night as he meets Ed's eyes, after he put that ‘invincible' all-state opponent on his back the first time. The smile still in place the next day as the team watched game film and Coach Ed replayed that moment no less than a dozen times as that kid and the rest of the team learned that nothing was impossible.

“I've also seen Ed's face light up when some of his boys, now adults, stop by to say hello and update him on their lives,” she continued. “That was always Ed's payoff and a well-deserved one at that.”

I only wish Coach Lenius could have been there to see how many of his “babes” and “big uglies” showed up to send him off. The church was packed with enough former players to form sides and play four quarters—even some of the pretty boys from the skill positions showed up (you know who you are).

During the service—which was full of tributes from players dating back to 1978 and earlier—my dear friend David Nelsen next to me in the pew nudged me with his elbow and pointed at something on the funeral program. There, big as life, were two words under the heading “Honorary Pallbearers”:

John Judge

And with those two words, as with Sloane Wallace, that feeling of surrender, forgiveness, and understanding came flooding back. And something Coach Lenius also loved, the feeling of victory. Sing it, Coach!

You can’t ride in my little red wagon!

The front wheel’s broken & the axel’s draggin’!

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

Mike Judge bravo. Tears to my eyes. Your comment of Coach putting his hand behind you head pulling you into his head gave me shivers and all I could think about was eyes staring into your soul. You know what he said was authentic. He was one of my biggest inspirations in my life. I would get one of his quotes that stays with me to this day. He would grab me like you head to head and say “Biggin you can never quit. We never quit” He spotted me when I set my bench press record. Head to head then the words “Your going to do this and you don’t quit. “ thanks brother for your article he was great man

Bravo ! As a player on Coach Eds first team in MC - all comments spot on. Thank You