The Tragedy of Hong Kong, and Why It Could Be Coming to a Geopolitical Theater Near You

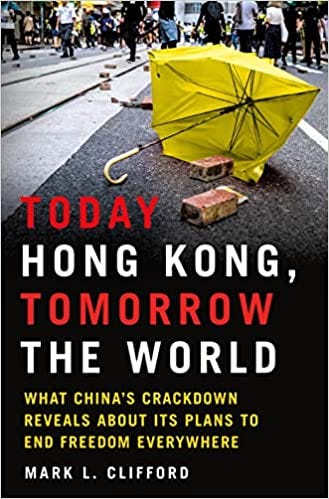

A TFP conversation with Mark L. Clifford, author of the tragic and alarming new book 'Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow the World: What China’s Crackdown Reveals About Its Plans to End Freedom Everywhere'

By Michael Judge

When I reach Mark Clifford, author of the new book Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow the World: What China’s Crackdown Reveals About Its Plans to End Freedom Everywhere, he’s feeling guilty for being free. He’s at his home in East Marion, N.Y., at the far end of Long Island, overlooking Lake Marion.

“I’m sitting here looking at this beautiful lake,” he says. “Beyond that is the ocean. I’ve got a red-bellied woodpecker in a tree not far from me. I’ve got birds flying by. It snowed last night. It’s a sunny day. I’m free. Right?”

Before I can reply, he’s half a world away, in his beloved Hong Kong, where the 64-year-old journalist spent most of his adult life, first as an award-winning writer and editor-in-chief at The South China Morning Post and The Standard, and later as executive director of the Asia Business Council (2007-21) and a board member of Next Digital, parent company of the now shuttered Apple Daily, the pro-democracy newspaper whose founder, Jimmy Lai, and seven others—the “Apple Seven”—are imprisoned on bogus charges of engaging in peaceful but “unlawful” protests. Lai also faces multiple charges under Hong Kong’s draconian national security law, passed in June 2020, including “collusion” with foreign forces, the penalty for which could be life in prison.

“I’m free,” he says. “But Jimmy, the Apple Seven, and hundreds of others are in prison. Jimmy is in a maximum-security prison for God’s sake. Every time they take him out, they manacle him. It’s 30-something pounds of manacle chains for a guy who is a 74-year-old diabetic, who has never done anything but preach nonviolence. And they want to humiliate him like that, like he’s some kind of animal. It really is inhuman.”

It’s hard to imagine Jimmy, a bear of a man with a booming voice and gentle spirit, weighed down by chains. It’s not just hard; it’s painful. Like Clifford, I’m a former Asia hand, and knew Jimmy Lai personally after I moved to Hong Kong in early 1998, not long after the June 1997 handover from Great Britain to China.

I was hired as an editorial-page editor for The Asian Wall Street Journal, and my colleagues and I met with Jimmy and other prominent journalists, activists and politicians on a regular basis. It was a heady time. Many hoped that Hong Kong’s tradition of economic liberty, rule of law, free speech and, granted, limited self-representation might soon blossom into greater democratic freedoms—not just in the Special Administrative Region but on the mainland as well.

But any hopes of the handover being a “Trojan horse” that would spread Western-style liberal democracy with all its accompanying rights and freedoms not only in the former British colony but in the Communist-controlled People’s Republic of China are now dashed. Indeed, Beijing’s recent crackdown on Hong Kongers’ rights to free speech, assembly, or any form of once common democratic debate is more reminiscent of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square in June 1989 than the fanfare of the handover ceremony in June 1997.

While our time in Hong Kong overlapped by at least a few years, neither Clifford nor I can remember ever meeting. So I ask him flat out: As a man who first arrived in Hong Kong in June 1992, a month before the last colonial governor, Chris Patten, and who literally holds a PhD in Hong Kong history from Hong Kong University, did he ever fall into the Trojan horse camp that believed the handover would help to spread liberal democracy in Hong Kong and China more generally?

He says, “I remember a time when others would be writing that, and I thought, ‘Hmm, that’s pretty optimistic.’ When I first arrived in ’92 all people talked about was ‘What’s going to happen in ’97?’ After the handover, it didn’t seem like much changed. I remember a former government official saying ‘What’s changed? Nobody talks about 1997 anymore.’”

“So what went wrong?” I ask.

“What went wrong is that most people underestimated the willingness and capacity of a Leninist party to do whatever it takes to maintain political control. During the 10 years that Hu Jintao was in power, from 2002 to 2012, things weren’t loose. But they were a bit looser partly because corruption was so far out of control. But the events of 1989 with the Tiananmen Square massacre and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union I think seared a kind of indelible memory in the Chinese leadership and fostered their determination to do whatever it takes to maintain political power—forever.

“I think it was Rupert Murdoch, and many others back then, who said things like, ‘I’ve never met a Communist in China.’ Well, you have, I thought. It’s just that while they were trying to get your money, they weren’t espousing Marxism-Leninism. Many people were naïve, and I include myself in that group. Like others, I indulged in wishful thinking sometimes.”

“But didn’t many, the British, especially, consciously delude themselves?” I ask rhetorically. “Didn’t many, against their better judgment, celebrate the handover as a diplomatic triumph, with the Basic Law guaranteeing ‘One country, two systems’ for at least 50 years?” It’s here that I mention Martin Lee, the grandfather of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement, and my interview with him in September 2019.

In that interview I refer to Mark Roberti’s 1994 book, The Fall of Hong Kong, a fascinating look into the behind-the-scenes machinations of the return to Chinese rule and the “unholy alliance” of capitalists and Communists that stacked the deck against Hong Kong’s chances of meaningful reform from the start.

In the 1996 edition of Roberti’s book, Lee writes in the introduction that “We now know that Britain knew all along — despite public assurances to the contrary — that China had no intention of allowing any meaningful measure of democracy in Hong Kong and that Beijing agreed to include provisions for an elected legislature in the agreement only at the eleventh hour to clinch a deal.”

“So, was the post-handover hoopla just a way to cover up what many Hong Kongers knew was a bad deal?” I ask.

In his book, Clifford writes that ‘For Hong Kongers, the fight against the extradition bill wasn’t about an obscure piece of legislation that would have little effect on most people. It was a breach in the dike that would sweep away the city’s freedoms.’

“My study was really focused on Hong Kong from 1945 to 1982,” says Clifford. “But it looked a lot at the business community and development of civil society, and it ended with Margaret Thatcher’s 1982 trip to Beijing when the handover negotiations began. Coming from the Journal, you probably know Bill McGurn?”

“Yes, of course,” I say.

“Well, then you probably know that he wrote a great book in 1992 called Perfidious Albion: The Abandonment of Hong Kong. He covers some of the same ground as Roberti, and points out how the Brits wouldn’t let the Hong Kong Chinese even have a seat at the table. And that drove people like Martin Lee and Emily Lau crazy, and for good reason. Britain definitely betrayed Hong Kong. It was an ‘unholy alliance.’ But probably with the Chinese business community more than the British business community. Again, this was nothing new. This had been a feature since the mid- to late-19th century, when the business community would again and again squelch all attempts to widen popular participation in not just politics but society in general, and that certainly continued. When the handover deal was done, they were like sunflowers: They just snapped. They moved from the British to the Chinese, thinking, ‘I know where my bread’s going to be buttered and this is what I have to do. I’ll just suck it up.’ … This unholy alliance is what made it possible. But now, business may find that it made a deal with the devil.”

That realization came for many with the attempt in 2019 to pass a hugely unpopular extradition bill. In his book, Clifford writes that “For Hong Kongers, the fight against the extradition bill wasn’t about an obscure piece of legislation that would have little effect on most people. It was a breach in the dike that would sweep away the city’s freedoms.” Protests against the bill, which was eventually abandoned, were massive, and included the business community.

“Why was 2019 such a crucial turning point?” I ask.

“Just because I have a PhD doesn’t mean I have all the answers,” Clifford jokes. “But it’s a great question. I mean, you see these moments of political turning—we saw it in 2014 as well with the Umbrella Movement, and it was a really interesting combination of circumstances. First of all, I think that many people, including business people for the first time, were genuinely concerned about the overreach that this law would bring. It basically meant that Hong Kong wouldn’t be a sanctuary anymore. It meant you might end up rotting in a jail in Shenzhen because somebody used their political connections to get at you. It would, in effect, erase the border that existed, the legal border, and really the physical protection that existed between Hong Kong and China.

“So you had the business community afraid for the first time, and then you had the government make a number of mistakes. There was a big demonstration that resulted in a lot of tear gas being fired, and legislators unable to physically enter the legislative chamber. And because the vote couldn’t take place that day, it was postponed and eventually scuttled all together, in part, because of an extremely heavy-handed police action, which further inflamed and catalyzed Hong Kong public opinion. The Hong Kong police very quickly went from being Asia’s finest to Asia’s most hated.”

“So how do you explain that?” I ask. “Was that due to intimidation from Beijing?”

“They groomed senior police officers,” says Clifford. “Many of whom are now running things. And as the British were leaving, the up-and-coming Hong Kong police officers were trained in political indoctrination, as well as crowd control and security operations, on the mainland. That contributed to a level of violence and intimidation on the part of the police that really, really angered Hong Kong people.

“I’m sure you’ll remember,” he continued, “if you went to the Tiananmen vigils, you’d have everybody from kids and parents with strollers to grandparents who could hardly walk taking part. And relations with the police were very friendly. But during the June 2019 demonstrations, the police wouldn’t even make eye contact with the protestors. They wouldn’t engage with them. They wouldn’t talk to them. The riot gear had stepped up. And then they started taking off identification. So if you got beaten up by a cop, you wouldn’t know who did it.”

Returning to his new book, published on Feb. 1, I remind him of the subtitle: What China’s Crackdown Reveals About Its Plans to End Freedom Everywhere. That’s a pretty big assertion. “Does China really have plans to ‘end freedom everywhere’?” I ask.

“People used to worry that Hong Kong was going to become just another Chinese city,” Clifford explains. “I would say it’s actually much safer to be in Beijing or Shanghai now because at least one knows where the red lines are. Hong Kong has become a kind of troublesome, outlying region that needs to be pacified like Xinjiang or Tibet. So the crackdowns are very erratic and uncertain and sweeping.

“But what’s different from, say, Lhasa or Ürümqi, is that Hong Kong was one of the world’s great global cities. It was, along with London and New York, one of the three most important capital markets in the world, the most important in Asia. It was a place that had an extremely lively free press, civil society, hundreds if not thousands of NGOs engaged in everything from environmental protection to women’s welfare, and, of course, had room for publications like Apple Daily. The fact that China can—by the way, without killing people—extinguish a free society shows, I think, the ruthlessness but also the capacity, and the skill with which the Chinese Communist Party is able to work even within open societies.

“Beijing often will work with corrupt elites,” says Clifford, political and business elites, but especially political elites, to invest in things that enrich their domestic cronies. Some of those things often have a high surveillance capacity when you’re talking about things like Huawei or ZTE. So it allows the government to control its domestic opposition or dissent.”

“Of course, China has sovereignty over Hong Kong. It doesn't have sovereignty over the U.S. or the U.K. And yet, in the run up to the release of my book, I had people say to me, ‘I’m sorry. I’d love to blurb your book, but I can’t. I have a son who’s working in Hong Kong, or employees in Beijing.’ A friend who runs an NGO in Israel, again, completely apolitical, but the Chinese Embassy there says things like ‘If we're ever going to cooperate with you, you have to use our wording on Taiwan, and a whole range of other things.’ We see it in Australia. We see it in Canada. We see it in the U.K., where China is increasingly assertive about flexing its muscles. It’s a funny mix of economic coercion and bully-boy tantrum tactics that are more like what you’d expect out of Kim Jong-Un.”

“But at the same time,” I say, “with foreign investment and spending programs like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s not just strong arming countries, it is pumping billions of dollars into their economies, in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, for example, and essentially bribing leaders into their form of authoritarian capitalism. It’s not just an unholy alliance with business people or threatening countries with intervention, but a long-term plan to influence, fund and indebt developing countries around the world, isn't it?”

“Yes. Totally,” says Clifford. “They use BRI that way, but they’ve dialed that back a bit. But I think your point about investing in Africa and other developing countries is a good one. Beijing often will work with corrupt elites, political and business elites, but especially political elites, to invest in things that enrich their domestic cronies. Some of those things often have a high surveillance capacity when you’re talking about things like Huawei or ZTE. So it allows the government to control its domestic opposition or dissent.”

“Right. Like in Burma,” I say.

“Yes. And then the people of the country are left with an indebted country that, like in the case of Sri Lanka, effectively has to surrender control of a major port to the Chinese. I think we’ll see other things like that,” Clifford continues. “It’s a kind of deathtrap of the most pernicious type. And at the same time, they’re buying the support of international bodies. The fact that China could even be on the U.N. Human Rights Council, let alone start driving a lot of the discourse, is part of this. By influencing these international agencies, the Chinese are increasingly driving the rules that are going to determine how we interact tomorrow.”

Returning to our mutual friend, Jimmy Lai, I mention the epilogue of his book, titled “A Newspaper Is Murdered, A City Mourns.” In it, Clifford writes: “The Chinese Communist Party is like a searchlight. It cannot see everything at once but when it turns the spotlight on an individual like Jimmy Lai, its power is scorching. When the party focuses on destroying someone, it usually succeeds.”

I wonder if that really applies to Jimmy. “What is remarkable about Jimmy,” I say, “and it comes out in the letters he’s written to you that you publish in the epilogue, is that somehow he is not destroyed. I mean, his empire, his livelihood, his freedom has been taken away from him. But he seems to have found some kind of peace in his role as a martyr for democracy and free speech. I guess my question is why was it so important for them to take down Jimmy in particular? And why is it so important that he never backed down?”

“If you’re a totalitarian government,” says Clifford, “to have even one individual like Jimmy Lai, who’s willing to stick his neck out and risk getting his head cut off–metaphorically at least, but maybe physically . . .” His voice trails off at the thought. “I mean, he could die in prison. He’s 74 years old. He’s a diabetic. And he has done nothing but he’s in prison indefinitely. Look at Liu Xiaobo. He was, like Jimmy, a proponent of nonviolence and free speech, a poet. He got the Nobel Peace Prize and he died in Chinese custody. They will go to any length to silence people. Because, it seems–back to your Trojan horse question–they worry that if today you have one Jimmy Lai, tomorrow you will have 10 Jimmy Lais, and the day after that 100. Then it’s 1,000. Then it’s 10,000. Then it’s 10 million.

“They crave legitimacy, but they fear their own people,” Clifford continues. “And they know that despite all the material progress, building the second-largest economy in the world, et cetera, their people don’t have freedom. And the fact that Jimmy Lai is, again, willing to sacrifice his life, shows how important and how valuable freedom is and everything that freedom means. Jimmy could have left Hong Kong. He could be living in his house in Kyoto or his apartment in Paris right now. He’s a British citizen, by the way. Yet he chose to stay, risking everything. Why? Because, as he said so many times, ‘Hong Kong gave me everything. I have to stand up for my people. I have to stay with my people, the people of Hong Kong.’ Remember, it’s easy to forget, he came to Hong Kong penniless, a stowaway, at the age of 12.”

“Yet they can’t risk having even one Jimmy Lai,” I say. “It’s a chilling thought, which shows who has the real power.”

“It really does,” says Clifford, who last August was named president of The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong, an NGO dedicated to democracy, human rights and the rule of law for the people of Hong Kong. “And it shows, I think, the CCP leaders’ fundamental insecurity and lack of certainty in their own legitimacy.”

By contrast, Jimmy Lai’s sense of certainty in his cause—buoyed by his love for his wife, Teresa, and his Catholic faith—seems to be flourishing, even behind bars. Perhaps the most stirring words in Clifford’s book, which itself is a moving testament to the character and endurance of Hong Kong’s democracy activists, weren’t written by the author but by Jimmy, in a letter to his old friend and fellow newspaperman:

I’m adjusting very well in prison. Without the distraction of the world I can concentrate on reading my books, especially books I didn’t understand [before], I can understand now. It’s such a joy. My family, colleagues, and friends and even people here have been very supportive. I know I must have done the right thing. The Lord has rewarded me with sweet joy and love. … I used to think I love[d] freedom the most. Now I know I love Teresa the most. I’m a lucky man. My life has been so wonderful. I can face whatever suffering [is] coming forth on me. … Yes, I’ve enemies. But funny enough I don’t have a bit of hate, not even a tiny bit. I tell myself if I can pray for my enemies and wish them well, I’ll have no fear. I really have no fear. I believe at the end righteousness and justice will prevail.

Like all TFP conversations, this conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

For more information about Mark L. Clifford and his new book, Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow the World: What China’s Crackdown Reveals About Its Plans to End Freedom Everywhere, visit his author’s page here. For more information about the The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong and how you can get involved, click here.

Arriving in your inbox later this week, the latest TFP guest essay, 永久性香港 FOREVER THIS HONG KONG, written by the brilliant XU XI 許素細, author of 14 books of fiction and nonfiction and one of Hong Kong’s leading writers in English. Absolutely thrilled to have her writing for TFP. Quite a coup for me, TFP, and all you loyal readers out there. So don’t miss it.

Cheers, MJ

Wow! What a comprehensive, eye-opening discussion of Hong Kong and the toxic reach of the CCP. We need to wake up to the steady encroachment taking place worldwide. Scary trends in Hong Kong from which there's likely no way out.