Superheroes

An early chapter from "Superheroes: A Memoir of Love, Madness, and Family," a work in progress.

By Michael Judge

The last time I saw my brother Steve before schizophrenia stole him away we were, appropriately, saying goodbye. It was late summer, 1979. I can still see him kissing my sister Katherine on the cheek before climbing into our family’s tiny green Datsun. A 21-year-old cadet about to begin his third year at the Air Force Academy, he’d spent the summer jumping out of airplanes high above the sun-baked fields of Little Rock Air Force Base.

The irony is almost comical. After free-falling from an altitude of 13,000 feet, Steve was bit by an encephalitic mosquito. Exactly when or where the bite took place we’ll never know. Did the mosquito strike as he floated through the summer air, his chute billowing above? Or did he swat at it after landing, only later noticing a patch of blood on the side of his neck?

What’s certain is that the ensuing brain inflammation sent him into a weeks-long catatonic state, and eventually triggered another brain disorder: schizophrenia. He began accusing his doctors and family members of being “imposters.” He was sure that I, his youngest brother, was “stealing his body,” and there was nothing any of us could do to change his mind.

But that summer, our second in Iowa, madness was the furthest thing from our minds. Two years earlier, my mother had divorced my father and moved the family from a suburb of San Francisco (a place she associated in her mind with mania) to Mason City, Iowa, where she earned a living as a substitute teacher, and, at the age of 40, endeavored to start a new life. For years she had longed to return to the Iowa of her birth, whether it existed or not.

Her dwindling hometown, population 490, was named for her grandmother Elma, whom she remembers vividly as a daring and beautiful woman who painted, loved the outdoors, and collected anti-FDR news clippings. Her mother, Ruth, was an English teacher; her father, Dinsmore (everyone called him Denny), was a gentleman farmer, town mayor, school principal and social-studies teacher. Grandpa Brandmill—we never dreamed of addressing our grandparents by their first names—fought in Okinawa alongside boys half his age and saw things, my mother used to say, that changed him forever.

In 1969, after her sister’s wedding, my mother brought a suitcase full of rich Iowa soil back to our home in the Bay Area, which was built on a jetty of reclaimed land and dirt speckled with broken seashells. “Smell it,” she said, opening a Mason Jar full of black, musty earth. “It smells like Iowa.”

The second summer after we moved she’d earned enough money to rent a small cabin on the south shore of Clear Lake, about ten miles west of our new, split-level ranch house in Mason City. The cabin wasn’t far from the historic Surf Ballroom, where Buddy Holly, Richey Valens and the Big Bopper gave their last show before taking off from the local airport and falling from the sky on Feb. 3, 1959.

Clear Lake was anything but clear. In fact, the emerald beads of algae that floated on its surface were so thick we avoided swimming altogether. The family was busy, and it was difficult to get anyone to stay at the cabin. My brother John had just received a full-ride scholarship to the University of Iowa where Hayden Fry was attempting to rebuild a Hawkeye football program famous for losing. My brother David was a junior in high school and more interested in the arts and pottery than water sports. Katherine, my sister, was entering tenth grade and busy with blow dryers, friends, and preserving her kindness in the cutthroat world of small-town cliques.

But my brother Steve and I had nothing but time. He wasn’t due back to the Academy for weeks, and I—about to enter the seventh grade—wanted nothing more than to spend time with him. So we spent the last days of summer reading, fishing and drawing our favorite superheroes from the pages of DC and Marvel Comics—Ironman, the Sub-Mariner, the Thing and Human Torch of the Fantastic Four; the Incredible Hulk. Most had been normal people, like you and me, before some terrible, unforeseeable event transformed them forever.

I remember thinking the only difference between a superhero, like Superman or Spiderman, and a super villain, like the Joker or Dr. Doom, was the ability to hang on to an ordinary, everyday existence. Superman had Clark Kent; Spiderman, Peter Parker. These weren’t just disguises or alter egos, they were tethers to the real world—without them, our heroes would lose their moral compass, if not their minds, and spin terribly, unrecognizably out of control.

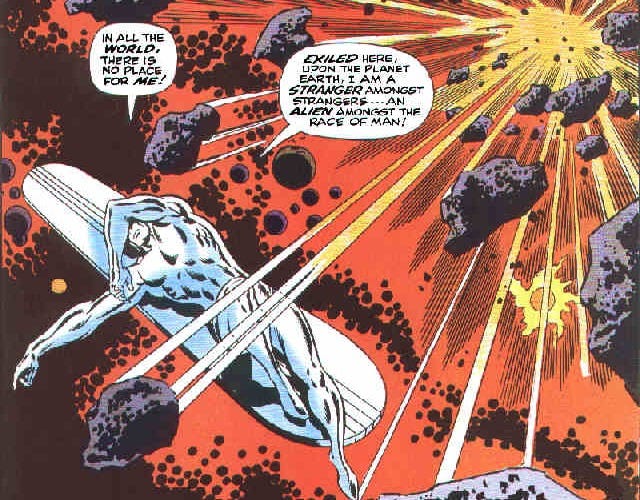

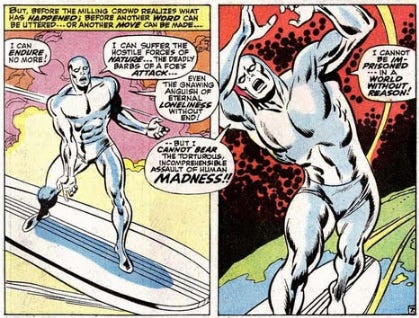

The most complex Marvel characters were those who were trapped, like villains, in their identity yet battled to remain moral beings. Ben Grimm of the Fantastic Four, who was transformed by cosmic rays into The Thing, a man of stone and strength who longed to do good but who had lost the ability to feel the warmth of another human being, to love and be loved. Or the Silver Surfer, a young astronomer named Norrin Radd from the planet Zenn-La who sacrificed his freedom to save his planet and family. Or Steve’s favorite, Bruce Banner, the scientist whose ambition and rage transformed him, time and again, into a reckless hulk of destruction.

In drawing these characters, my brother and I tried to capture their torment—each muscle-bound limb a symbol of something that had been lost, that could never be regained no matter how long or hard they struggled. There was no going back, just the constant battle to resist darkness and villainy—and the distant memory of what it was like to be normal.

I still dream of those last days with Steve on the lake. The summer was nearly over; the muggy Iowa nights were growing cooler. Eventually, it was time for Steve to return to the Academy, to its towering cathedral and sprawling courtyards in the Colorado Rockies. I’ll never know why for certain, but my brother wept when he said goodbye that day, as if somehow he knew this wasn’t just the end of summer, but the start of something beyond him, something unnamable, an autumn like no other.

To be continued . . .

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

Crafted well. An enjoyable read. Waiting for the continuation.

Subscribed. Brilliant writing.