Red Danielson: Constellation Winds

Ray Young Bear sings of the Red Earth at the entrance to the underworld.

By Red Danielson

This all ends with an endless note in the wind, & Ray Young Bear, one of our greatest poets, singing bird songs on the bank of the Iowa River, where, in 1980, a UFO appeared before Ray & his wife, Stella Lasley-Young Bear, at a location Ray tells me he & other members of the Meskwaki Tribe believe to be the entrance to the underworld. Maybe this is about that: UFOs, recalling what we can hardly comprehend. Maybe it is about the essential life within each of Ray’s poems & songs. It may even be about everything in the sky & under our feet, or about the rifle Ray emptied into the UFO hoping to take him & Stella into its gleaming metamorphosis of light, hovering only 60 feet above their heads in the dark sky 43 autumns ago.

Let me get you there.

I only want for you to be with me as my voice intertwines with your own, reading on to the next word, the next, the next. & which of the two is in your mind this moment? The UFO? The entrance to the underworld? Let them both have their place in your mind, & know not every doorway is framed in timber; some doors are bound by fluctuating tissues, all squeezing & letting go as they see fit, the way the iris holds the emptiness we call pupil. I’m only here to speak my voice into yours.

Be with me now. It’s all already happened. Be with me.

So, I woke up some morning with my youngest son whispering in my ear, “Daddy, wake up. Daddy, wake up. Daddy, wake up.” A fragment of a dream still played in my mind as he pulled me from bed to look out the back door with him, so he could show me what had happened while we all slept. Farm hands had worked through the night, clearing the corn & soy from the fields with combine harvesters. I looked out the back door to where the eight-foot stalks had been when I’d gone to sleep. “All gone,” my son said.

“All gone,” I agreed.

We live at the very edge of a very small town called Lone Tree. When the crops are high, the world is a bit smaller. When the crops are taken, it’s as though you can see to the other end of the state.

It was foggy that morning—everything grey & wet. I could hardly see the highway, just a hundred yards from my deck. I picked my son up, our faces reflecting in the windowpane separating us from the world. All gone.

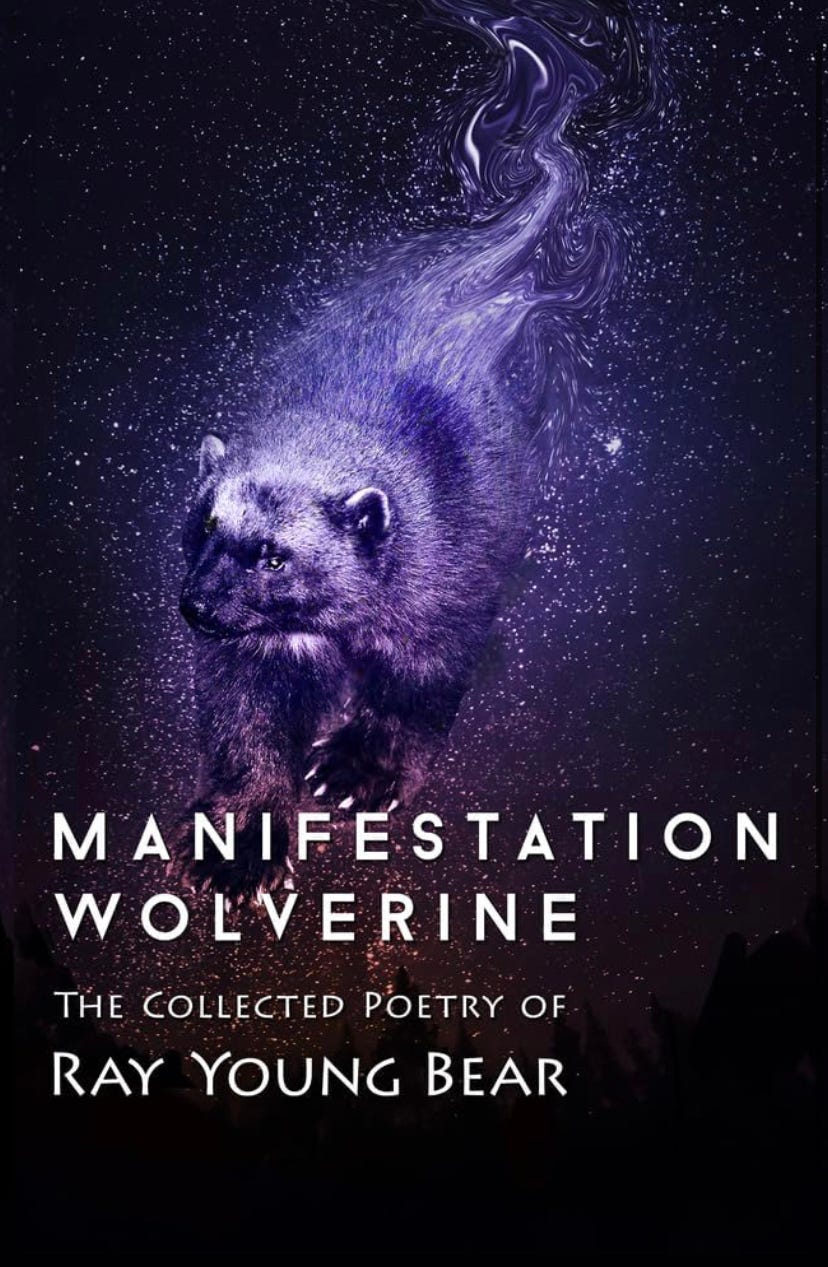

I’d packed my car by midmorning with all of my painting equipment. It was the day I would finally meet Ray Young Bear & paint his portrait. I started reading Ray’s poetry 10 years back, when I was 23, two years before his collected book of poems, Manifestation Wolverine, winner of the American Book Award, was published.

Ray sang his song, which was, as he told me, the song of the grackle—the black bird of the fields, covered in chatoyant rainbow spills, that gather in singing plagues. I cannot tell you the words of the grackle’s song, not a single one of them, only that they made me cry, just then, that very moment.

I stood beneath the open back hatch of my car, running my finger along the blank canvas & staring into the grey mist where I figured the horizon must be. Hundreds of grackles called from the fields where they searched for bits of corn dropped by the combines. A group of grackles is known as a plague of grackles. It’s the only time I’ve known a plague to be pleasant, & though they are not considered a songbird, I love their song more than any other.

I stopped at the dollar store outside of town for cigarettes. I felt like smoking a few on the drive to the Meskwaki settlement, & most likely a few more while painting Ray’s portrait. The elderly woman behind the counter, with deep creases around her eyes & mouth, furled her prominent brow as she told me she was disappointed in how often the kids these days say fuck, & that she was disappointed in her 25-year-old cockatoos because they say, “close the goddamn door, it’s cold out.” She handed me a pack of 100s cigarettes. “They say this even when the door is closed, even when it is summer, they say it.”

I told her cockatoos seem to mimic, not comprehend.

“Well, who taught them to say that?” she asked.

I scraped my fingernail over the plastic covering my pack of cigarettes until it made that lifeless sound. The creases in her tired face made it so I felt something like generosity warming in my belly.

I asked if she wanted an eighth of mushrooms, & she curled her lips up a second & stared at the ceiling before she said, “I can’t digest fruit no more, but that shouldn’t make a difference.”

The hills of Highway 30 were golden where farmers had emptied the fields. You could really see it in all this: how everything here once slept under a sea for endless lifetimes, then pushed itself up from a dream & again suffocated under a distant sleep as glaciers laid upon Iowa like an incubus starved for human love.

Wet wind flapped into my window as the smoke from my cigarette fled toward the thousand feet I’d just inhabited.

When Ray & I connected over the phone back in September, he asked if I would be okay with him holding the rifle from the night with the UFO in 1980 when I painted his portrait.

“I would be cosmically depressed,” I told Ray, “If it wasn’t in the portrait.”

“What would you think,” Ray asked, “about painting me where the UFO visited Stella & me, all those years ago?”

Christ, I hadn’t even laid eyes on Ray, but it was just one of those things. I knew I would be telling this story again & again & again by the time it was all said & done. You get a sense for this sort of thing when you task yourself with the obsessive need to understand story. You know from the very beginning the ones you’ll hold most dearly.

We talked for 47 minutes, mostly about UFOs—a little about poetry. At the end of the call, we said our goodbyes. Ray stopped me short of ending the call. The register of his voice had become more serious than he’d allowed throughout the entirety of our conversation. “You should know, some Meskwaki believe the location where you’ll paint my portrait is the entrance to the underworld.”

& what sort of man am I to be enticed by such a thing as this?

I let what he’d said rest in me a moment. I can’t describe the sensation that washed over me then. But I know when to follow when essential moments are hoping to lead me to what the moment knows & I do not. “Take me,” I said, “to the entrance to the underworld. I would love to paint you there.”

The fog hadn’t broken when I arrived. I parked on the road outside Ray’s house & walked up the drive. I wanted to feel the entirety of the place. Ray’s drive curves like a crow wing as you leave the highway. You can’t see the house from the road. You see shining sumac, in their red dregs of fall, their leaves redder than the image of any blood imagined inside your mind just now. It sutures the gravel drive around a bend to the house. The skirting of trees, filled with maple, red oak & hackberry had all but dropped their leaves. So, it was just the dangling red sumac leaves, like a low forest of knives hanging just above the horizon.

I heard my name called from the trees. There was Ray, walking around the curve in the drive, rifle in hand. He wore a red Bandana, cyan shirt, camouflage coat. We had a nice little chitchat in our fog-darkened jest of timber, all that red quivering in the wet wind just above our heads. We decided the painting should be done in front of all those shining sumac. We stared into the red leaves the way the first men must have stared into the first flame. “Here,” we agreed, still staring into the leaves, “would be best.”

We’d get to the underworld in time.

Ray, I must address you here, as I am sentimental, weak at times, prone to prophecies & substances. It used to be I heard my own voice when I read your poems. I can’t help now but to hear you, since you spoke into the phone the secrets of the wolverine, appearing as it did as you held your young son in your arms 20 some odd years ago. I’ll never read your poems in my own voice again. So, what gift could I ever return to you, my brother?

I will fall short trying.

The foggy noon hour muted dramatic shadows & light from the world. It made it so that everything wore a similar light source, which can confuse the eyes when they are looking particularly for light & shadow. I scraped globs of paint all over the canvas, long violent pulls, recreating the thin timber curving behind Ray, where he’d set up in front of the shining sumac.

I started painting 11 months ago, after eating four grams of psilocybin mushrooms & hearing an ethereal voice tell me I was to start painting. It has not even been a year since I painted my first painting, so I can’t give much advice as far as painting goes. But I can urge you to listen. Listen always, because every single thing we do in life leads us to a somewhere, & where is it you wish to end up?

I paced the gravel drive, side-to-side, trying to find the angle to best portray Ray. The conversation had drifted to a shared knowing between the two of us: there are more ancient, more sacred things than us inhabiting these places we know, some of which have revealed themselves to the two of us, though we still, years after having experienced some of these things, do not understand them. Ray held his rifle across his lap, his right arm had drifted into the air, making a fist. He’d closed his eyes & begun to ripple his fingers as he tried to find the right words in his mind. This was it; this was the Ray I would paint.

See, I’m trying to see a splinter of the individual that has remained lifeless from the moment they became human. I must give life to what I see. This is my duty in the portrait. The trick is to know the journey the image desires; does it wish to crawl toward life. Or does it wish to fall violently. The image & the individual are not one & the same, but the portrait intertwines the two in a particular moment in time, in this case just before Ray found his words.

“Animism is something I have over other poets,” Ray said, “Only because other poets don’t know what it really is. White America has been taught to discount anything that moves in the night. For us it’s the opposite, if it moves in the night, you’ve got to be careful. That’s what they teach you here.” Ray had found his words, but his eyes remained shut, his fingers still rippling within their gathered fist. “These trees around us,” Ray continued, “I pray for these trees.”

Ray was silent for some time after this. He’d gathered inside himself. I figured he was praying just then. For the trees, for the cryptic manifestations, showing themselves in the night to the Meskwaki seer, the poet who knows of the essential life in all of this.

It was when I’d lit the last cigarette of the pack & dipped an angled brush into the spread of cadmium red to paint the hanging leaves just around Ray’s aura when he asked, “Meskwaki, do you know what it means?”

I admitted I did not.

Ray said the words slowly, “MESKWAKI—People of the Red Earth.”

I ask you again to be with me. See it in your mind: the fog over the earth like a cataract obscuring the eye of all, look down into the gravel drive where Ray & I stand across from each other, saying farewell. The rifle leans against my easel. Ray has pulled a knife from his belt. He leans down to the gravel & cuts a map into the earth. He taps a place in the rock saying, “This is where we had the encounter. It’s about a mile into the floodplains. That UFO followed us for a mile. We stopped at what we call the stonehouse & turned onto the highway. That UFO went over us & aligned with the old railroad tracks. We were driving 80 miles per hour. It was traveling with us until we got to the bridge. At the bridge, Stella found one last bullet for the rifle. I got out at the end of the bridge. The UFO was above some cottonwoods here.” Ray taps the gravel again with his knife. “That’s when I spoke to it. I said, ‘This is the last one we have. I want you to go away.’ When I fired the last bullet into it, the UFO shot up into the sky & became like a star, instantly.”

Eighteen days later, on Ray Young Bear’s 73rd birthday, we cross the road in full sun toward our otherworldly destination on the Iowa River. Yes, the entrance to the underworld. A ten-point buck, deep in the testosteroned fevers of the rut, runs out of the tree line in front of us, its tongue hanging out of its mouth as it smells its way on the trail of a doe. “That’s right,” Ray says as the winds carry through the golden reed grasses gathering closely over the river bottoms. “It’s hunting season. We must be careful.” Ray carries his body close to itself, a gesture filled with the serenity of 73 years.

We stared then into the still river, low from two seasons of little rain, reflecting the world back into our eyes over the gold-leafed mirror singing in the wind. I pulled a cigarette I’d packed with Durban Poison, an astute sativa that pulls the mind to wanderings & shielded my lighter from the wind. So much left me as the smoke carried away quickly from the two of us.

“It’s right there.” Ray pointed his earth-toned finger to a spot on the bank. “It’s right there.”

Two-hundred yards down river, in the shallows near a bed of gravel, a group of young men, oriented in a line, pulled at something I couldn’t see. The sun danced silver & pink over the river where they struggled. “What are they doing over there?” I asked.

“Who knows,” Ray said, “Just being men.” Then Ray began to sing. His song was in Meskwaki, Ray’s first language, one untranslatable by me. We stood there like that, the strands of grass bending to the river while ribbons of words unknown to me unfurled from Ray’s throat. The notes tumbled from Ray like gentle feathers falling to the earth.

I looked at the place in the river he’d pointed to. It was right there. The trees were still. In the steel blue sky, a few dozen geese flew in their V formation, hoping to escape the dead winter before all this is gone.

Ray sang his song, which was, as he told me, the song of the grackle—the black bird of the fields, covered in chatoyant rainbow spills, that gather in singing plagues. I cannot tell you the words of the grackle’s song, not a single one of them, only that they made me cry, just then, that very moment. I turned from Ray Young Bear, so that he would not see the tears gathering in my eyes.

All the dead voices made endless sounds of wings beating in the reed grass. Be with me now & then as I tell you. Listen. My voice is yours inside you.

My god, I wish I could tell you how golden this world is.

Red Danielson, a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, is a poet, screenwriter, and painter. His work has appeared in The Iowa Review, Haiku Journal, CERASUS, Three Lines Poetry, and Subterranean Quarterly, among other publications. This piece, an earlier version of which appeared in Little Village magazine, was adapted from an ongoing project pairing his prose with portraits of poets, writers, and artists. For more on Danielson’s work click here.