Never Again

I've made a promise to myself: Say a silent prayer every Aug. 6 at precisely 8:15 a.m., and share the stories—each year, without fail—of the atomic-bomb survivors who shared their stories with me.

By Michael Judge

TOKYO — Tomorrow morning, on Aug. 6, just before the clock strikes 8:15, thousands of visitors from around the globe will gather at Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima in recognition of the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of that now bustling and beautiful city of 1.2 million souls. They will reflect on the more than 140,000 men, women and children who died in that horrific, world-changing instant, and in the hours, weeks, months, and years that followed. Above all, they will repeat these two words—half promise, half prayer—“Never again.”

I won’t be in Hiroshima for the anniversary this year, but I’ve visited numerous times over the past 30 years, most recently in 2022 on a trip with my wife and our young—half-American, half-Japanese—son. Seeing the city through his eyes, feeling him struggle to take it all in, was nothing short of a revelation for this often world-weary journalist. Part of that revelation was a promise to myself: Say a silent prayer every Aug. 6 at precisely 8:15 a.m., and share the stories—each year, without fail—of the atomic-bomb survivors who shared their stories with me.

As many TFP readers will know, I first visited Hiroshima in 1994 on assignment to write about the Chugoku Shimbun, a daily newspaper just one kilometer from the hypocenter of the blast. What I learned on that trip was this: The 15-kiloton atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima was detonated at precisely 8:15 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945, 500 kilometers above the city. The explosion created a massive fireball, with temperatures near the hypocenter reaching 3,000 to 4,000 Celsius (an iron bar melts at half that temperature). Of the 76,000 buildings near the hypocenter, 70,000 were destroyed. Of the 300 employees working at the Chugoku Shimbun that morning, 113 were killed. Yet, incredibly, thanks to the use of other papers’ printing presses, and a press the Chugoku had moved out of the city, the paper resumed publication just days after the bombing and is still in operation today.

It was during that trip, three decades ago, that I first fell in love with Hiroshima—the city, its people, their resilience, and the great responsibility they feel as the first human beings to have suffered the horrors of a nuclear attack. I returned several times shortly after that, once to interview the mayor of Hiroshima in the weeks before the 50th anniversary of the bombing, once to attend the 50th anniversary, and once to interview three hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bomb). The word holds a kind of hallowed and, sadly, taboo status in Japan, and can be broken down into three parts: hi, which means to suffer; baku, which means explosion, and sha, which means person.

The hibakusha as a people were long shunned by the general population, especially outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but in recent decades have received the compassion and respect they deserve. This is in large part due to their willingness to tell their stories, to share their suffering with others, and above all the strength, moral clarity and dignity in their constant refrain: “Never again.”

As John Hersey showed in Hiroshima, his unequaled report on six survivors that filled the Aug. 31, 1946, edition of The New Yorker, later published as a book, the victims of the atomic bomb were ordinary men, women and children whose lives were obliterated or changed forever by circumstances beyond their control.

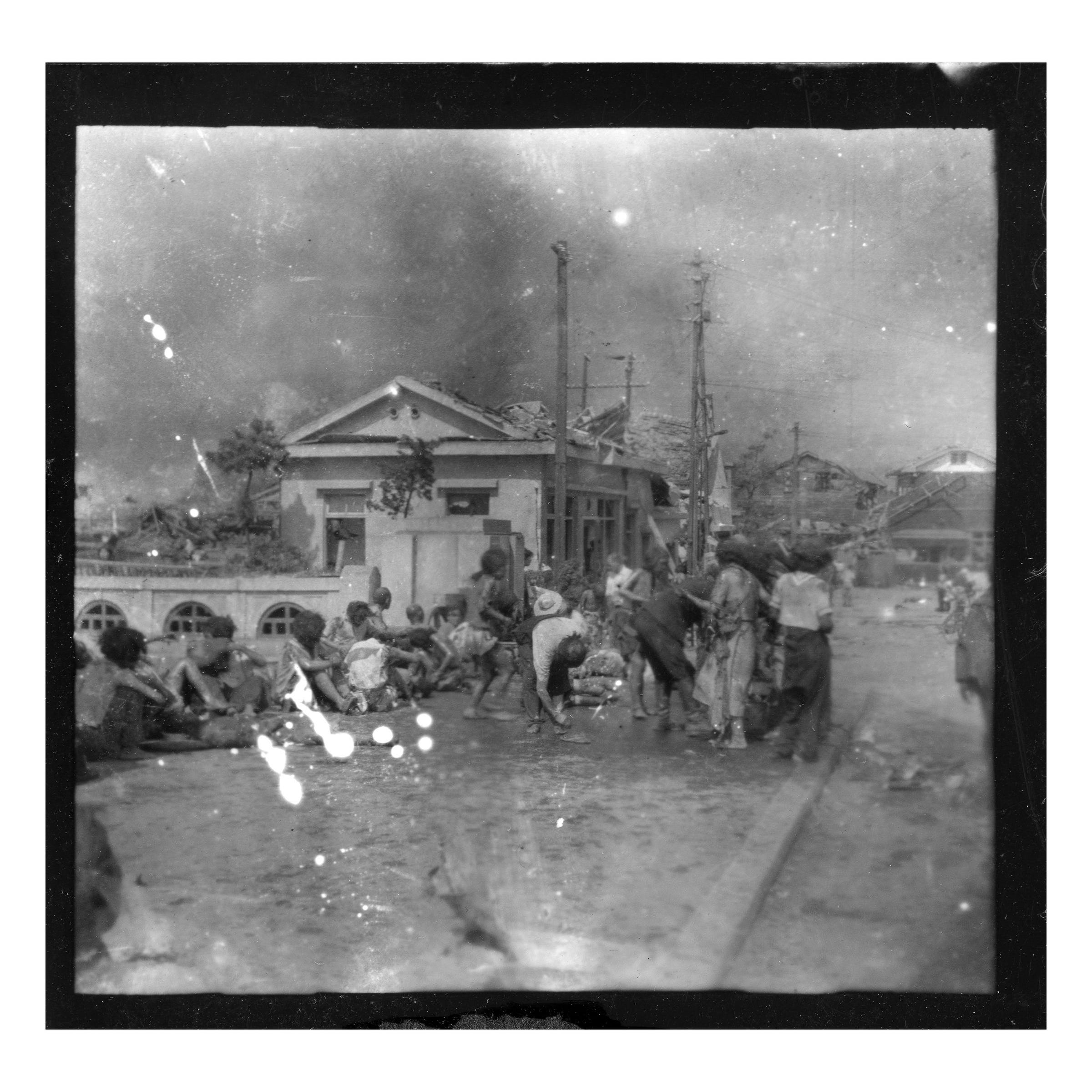

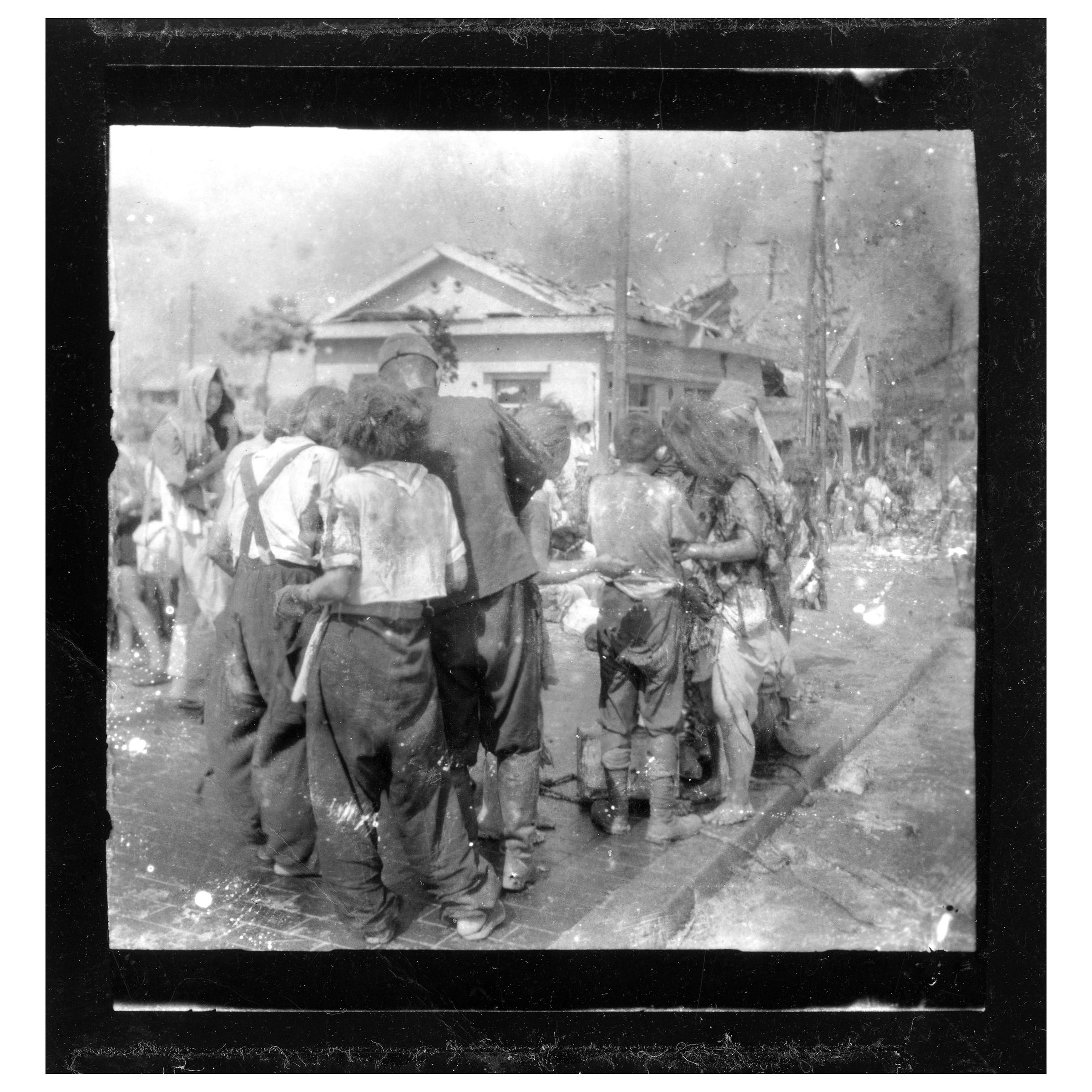

The first of the hibakusha I interviewed was, like me, a journalist. A photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun, Yoshito Matsushige was at his home 2.7 kilometers from the hypocenter when the blast occurred at 8:15 in the morning. His immediate reaction was to grab his camera and head toward the fire. But when he saw “the hellish state of things” he couldn’t bring himself to take pictures. “It was great weather that morning,” he said, “without a single cloud. But under that blue sky, people were exposed directly to heat rays. They were burned all over, on the face, back, arms, legs — their skin burst, hanging. There were people lying on the asphalt, their burnt bodies sticking to it, people squatting down, their faces burnt and blackened. I struggled to push the shutter button.”

After more than 30 minutes, he said, he finally brought himself to take two pictures of people, horribly burned, who had gathered on Miyuki Bridge, about 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. Many were middle-school children, their bodies terribly burned. Someone was applying cooking oil to their wounds. He remembers asking them for forgiveness, wiping away his tears, and saying “I just took a picture of you as you are suffering, but this is my duty.”

In all, Matsushige snapped his shutter just seven times, the only photos taken in Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. He died in 2005, at the age of 92, a dedicated peace activist who shared his story with people around the globe, including before the U.N. General Assembly.

That same summer I spoke with a survivor who, after breaking a long silence, had been sharing her story with schoolchildren for a decade. Seiko Ikeda, a 63-year-old retired teacher and grandmother of five at the time, was 13 when the bomb changed her life forever. Only 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter of the blast, she was exposed to massive amounts of radiation and suffered severe burns on her face and body. Over the next 20 years she would undergo a series of 15 operations to remove the scars that once covered her face and arms.

In 1984, she began sharing her story with students who visited Hiroshima on school trips. She did so because she felt compelled to “convey to the younger generation the terrible reality of nuclear war so that the tragedy is never repeated.” When I interviewed her, a student who had heard her speak a decade earlier had recently returned to Hiroshima and told her how much her story had influenced her life. “She still had what I had told her emblazoned on her heart,” Ikeda explained. ‘Your story will always be a part of me,’ she said. ‘You helped me decide what I wanted in life and gave me the courage to pursue it.’ I was very moved.”

In 1985, in recognition of the 40th anniversary of the bombing, Ikeda traveled to all countries with nuclear arsenals, including the U.S., China, France, Great Britain and the former Soviet Union, to tell her story.

My final and most difficult interview was with a gentle, 64-year-old man named Yoshitoki Inoue. A retired teacher, Inoue was 15 and just beginning teachers’ preparatory school when the bomb killed his father, mother and younger brother. Their house was near the hypocenter. That morning, his mother was walking his little brother to nearby Sei Hospital, directly below the hypocenter, when the blast occurred. “You couldn’t distinguish between the dead,” he told me. “So I couldn’t find them.” His brother, a sixth grader, had been sent home from school a safe distance away due to an illness. “It’s like he came home to be bombed,” he said. His uncle, who had seen his mother and brother that morning, survived by wading into the river. “His face was puffy and swollen, and his body was burnt,” Inoue said. He was a city councilor. He died three days later, on Aug. 9, the same day as the Nagasaki bombing.

Inoue’s life was spared because, as he explained, his school was a safer distance away, on the other side of the Kyobashi River. “I was behind Mt. Hiji,” he said, but he still was thrown to the floor. “The window right above me flashed so bright … after a few seconds, the building shook like this [gesturing with his hands and making a rumbling noise], and the window frames and the glass from the windows fell on top of us.” He realized that “there were pieces of glass in his arms and legs.” Still, he tried most of the day to cross the Kyobashi River to get to his family. “But I couldn’t,” he explained, “because the other side was a sea of fire.”

The next day he crossed the river into the city. It was then that he discovered his uncle, swollen, burned and muddied, and learned that his father, mother and little brother were gone. His older sister, who had married and survived the bombing in her home, took him in and raised him as her own. He even took her husband’s family name, changing his name from Sakai to Inoue.

Inoue, from what I could see, had no self-pity in him, no anger. Instead, like the good teacher he is, he tells his students that “from the soles of your own feet, the heart of peace is the heart of kindness. Don’t discriminate. Don’t bully.” That kindness is revealed in a story he told me about the day after the bomb was dropped. He came across a little boy who asked only for a glass of water. So he helped him. He went for water but when he returned the little boy had died.

As former U.S. President Barack Obama said during his historic 2016 visit to Hiroshima, “Mere words cannot give voice to such suffering, but we have a shared responsibility to look directly into the eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again. Someday the voices of the hibakusha will no longer be with us to bear witness. But the memory of the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, must never fade. That memory allows us to fight complacency. It fuels our moral imagination. It allows us to change.”

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

I am with you, dear sobrino 🙏❤️

Tomorrow at 9 pm will join our local ceremony to honor the memory of the victims of atomic horror! Never again!!! Abrazo 🤗