Molly Wesling: Czesław Miłosz's Hundred Acre Wood

Upon the birth of her son, writes Molly Wesling, the great poet sent a gift: "The Complete Winnie-the-Pooh." The inscription read, "To Nicholas Wesling Gerber, that you may enjoy it as I did."

By Molly Wesling

April 8, 1995 Dear Mr. Creedon, Thank you for your letter of March 18, 1995. The first requirement to become a writer is to get a good education, possibly with a knowledge of classical languages—Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, a training in history of philosophy, and world literature. The rest will follow. Sincerely, Czesław Miłosz

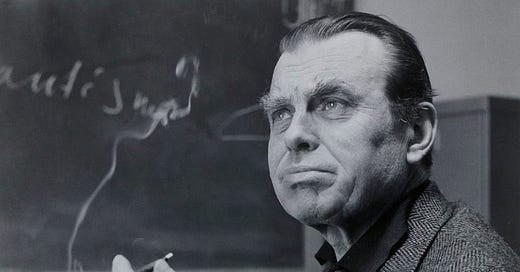

For five years I worked part-time for the poet and Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz at his home in the Berkeley Hills. Miłosz was 79 when I started taking dictation in Polish and English, helping him answer queries and invitations, mostly finding ways to say “no” in the gentlest of tones. Every so often though, I’d get to transcribe a gem like the letter above.

Once a week I caught the bus to 978 Grizzly Peak Blvd. Miłosz would greet me at the door, shake my hand with a slight bow, and invite me to his study. By then he had a facial tic: his shaggy eyebrows twitched up and down as he talked. Carol, his American second wife, a lovely, funny woman with a southern twang, would bring Miłosz a glass of vodka. I’d whip out my steno notebook and get to work. Several hours later, Miłosz or Carol would drive me home, a steep descent and a slightly unnerving experience when Miłosz was at the wheel. The view was glorious—often the sun was setting over San Francisco Bay—but I would silently fret about the brakes on his mid-1980s sedan, and the odd headline a mishap might inspire.

At the top of his property near the street, Miłosz had a carriage house that he rented out to graduate students, including the sociologist Ted, with whom I fell in love, and, when Ted moved out to live with me, my old friend AnneMarie, a lawyer-in-training. Neither of them had much use for poetry or deference to the landlord called by Joseph Brodsky one of the greatest poets of our time. AnneMarie referred to him as “Cheesy Meatloaf”—her approximation of his Polish name. But she was impressed by the gold medallion that rested on a side table next to the phone in the living room. I’m pretty sure any visitor who used the phone took a surreptitious moment to trace the visage of Alfred Nobel and hold that orb up to the light. When Miłosz went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for a year as a writer-in-residence, leaving Ted in charge of his cat and his rhododendrons, the medallion remained in situ, just another knick-knack amid the piles of books and papers. Miłosz himself was not much impressed.

“Christopher Robin is the poet, come back to reassure us that growing old and dying is probably just a dream . . .”

Another part of my job was to open and sort the mail, setting aside the letters from Miłosz’s admirers. I wondered about the crumbs tucked into letters from his Polish readers. Later it dawned on me that they were the bruised remains of communion wafers after a journey through the international post. Miłosz dutifully signed blank cards for autograph seekers and sent photos of himself when requested. He didn’t reply to everyone, but some letters caught his fancy, and he would strike up a correspondence—as with this aspiring writer, whose intelligence and longing jump out from the page:

Guilin, Guangxi 541001 P.R. China October 14, 1993 Dear Mr. Miłosz, . . . Perhaps having read western literature and philosophy too much, I appear to be a stranger in my own country. Now, I try hard to improve my English writing ability, hoping to express deeply my understandings of Chinese culture in Standard English someday. As I have longed to be writer from a child, it is not my end to come to America to study Engineering, but I have no other choice. In China, it is difficult to change one’s occupation, at the same time, I am not willing to waste nine hours in a factory every day. I wish I will be admitted to a literary school to read William Faulkner, to study his cycle of stories about Yoknapatawpha County. I have enjoyed reading an essay excerpted from “Native Realm: A Search for Self-Definition.” Would you please send me this book? For an ordinary Chinese youth like me, it is impossible to obtain any of the original masterpieces. I have taught myself Spanish in order to read Garcia Marquez, for example, but I never get “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” With kindest regards, Wei Rui

I kept a copy of Wei’s letter because I planned to look him up one day. Did the extraordinary youth from Guangxi, a mountainous region in the far southwest of China, become a Faulkner scholar? I don’t know. The answer might lie in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, where Miłosz’s archive now resides.

Sometimes the correspondence had odd results, as in the case of a young fan in her early 20s from Japan. She had clearly read Miłosz’s work—her letters were lucid, full of emotion and insight, written in perfect English. Then one day she showed up at Grizzly Peak Boulevard and rang the carriage house bell. Miłosz and Carol were living in North Carolina that year, and Ted answered the door. The woman introduced herself and asked to see her fiancé, explaining that she had traveled all the way from Japan to marry Miłosz. In a panic, Ted called me and we managed to track down one of Miłosz’s sons, who lived in the Bay Area. After many hours of negotiation with the Japanese Embassy and the woman’s family back in Japan, a car arrived to whisk her away. She never had a chance to lay eyes on her beloved. A few months later, a package from her arrived. Miłosz asked me to open it and describe the contents. It was a trove of pastel-colored sweets, wrapped in exquisite papers, emanating a subtle perfume.

The indignities of aging were on the poet’s mind. He was translating the poems of Anna Swir (aka Świrszczyńska, 1909–1984), his friend from Warsaw, into English in collaboration with Leonard Nathan. Swir wrote about what happens when bodies decay and disappoint, and Miłosz admired her candor, rare for a Polish woman of her generation. His own writing from this period onward is full of such meditations. “They were betrayed by their bodies, once beautiful and ready to dance. Yet in every one a lamp of consciousness is burning, hence their wonder: ‘Is this me? But it can’t be so!’”

Still, the world rose up to smooth the poet’s path. One of the perks of being a Nobel laureate at University of California, Berkeley—at that time there were about 15, Miłosz the only winner in a non-scientific field—is your own parking space on campus for life. Miłosz also had the privilege of scoring a table at a moment’s notice at the wildly popular restaurant Chez Panisse. In Berkeley these were fairy-tale prizes, like flying carpets or enchanted pots that never run out of porridge.

Over the phone in the fall of 1990, Miłosz described where to catch the bus to his house and cautioned me about the many “lacunae” in the bus schedule. I knew then I’d caught the golden ring of part-time jobs. In between letters I jotted down a few of his asides. I’ve saved my notebooks, which is why I can quote from them 25 years later. Once, Miłosz looked at me as I was writing and said, “I used to be left-handed too, but they beat it out of me.” On Joseph Brodsky: “he is a genius”; Robert Frost: “marvellous”; the Laments by Renaissance poet Jan Kochanowski: “should be ranked with the world classics”; and my favorite: “these poems are awful” (I can’t say whose).

Miłosz and Carol were away for the year of 1991–92. I collected the mail and sent it to Chapel Hill. Ted was in charge of watering the bushes of the main house and tending to the needs of Tiny, the ancient Russian Blue who appears once or twice in the Miłosz oeuvre—both as himself and as a representative of the violent animal world. Through our weekly tryst at Miłosz’s aerie, Ted and I had become a couple, complete with gray cat, like the “Old World Landowners” from Nikolai Gogol’s short story of that name. When the 81-year-old Master finally arrived back at his Berkeley home, he immediately noticed the dying rhododendrons and Tiny’s untidy litter box and was annoyed. Miłosz climbed back up the flagstone path to the carriage house and commenced a dressing-down. Later that evening he returned, this time to offer Ted a heartfelt apology the way only Miłosz could—eyebrows twitching, a humble bow of the head.

After Carol’s death from cancer in 2002, Miłosz wrote an elegy for her, “Orpheus and Eurydice” (translated by Miłosz and Robert Hass). It was one of his last poems before his death in 2004 at the age of 93. Here are a few lines:

He remembered her words: “You are a good man.” He did not quite believe it. Lyric poets Usually have—as he knew—cold hearts. It is like a medical condition. Perfection in art Is given in exchange for such an affliction. Only her love warmed him, humanized him. When he was with her, he thought differently about himself. He could not fail her now, when she was dead.

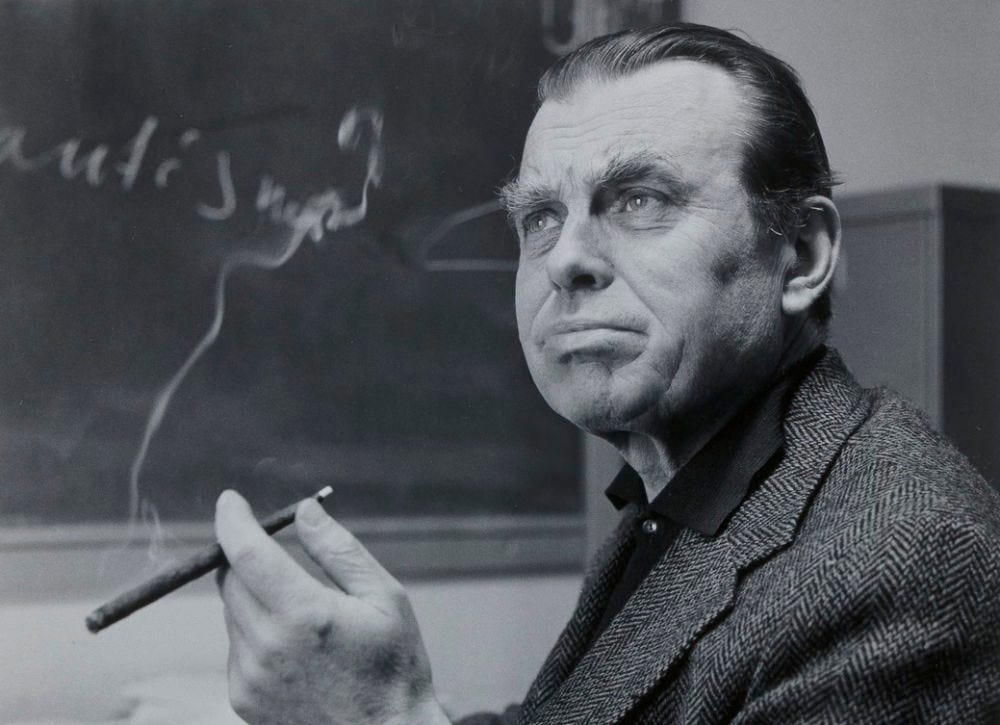

I suspect it was Carol’s idea to bring us a wedding present (a wooden tray) and send another gift upon the birth of our son in February 1996, after we had moved to Oregon. But I am certain that Miłosz picked out the second gift, which arrived at Christmas: The World of Pooh: The Complete Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner, by A. A. Milne. The title page carries an inscription in the poet’s hand: “To Nicholas Wesling Gerber, that you may enjoy it as I did. Czesław Miłosz. Dec. 4, 1996.” Miłosz was 15 years old and living in rural Lithuania when Winnie-the-Pooh was first published in 1926. Exactly when did he enjoy it? Did he fall for Piglet, Owl, and Pooh while practicing English in his teens, or much later, in exile, while reading to his own two sons? I neglected to read Winnie-the-Pooh to my children. The small bear of little brain was no match for the modern British wizard-boy who saved the world from evil time and again. I regret now the missed opportunity to dwell for a time in the Hundred Acre Wood, where fears are an ordinary part of life but do not linger in our nightmares like Dementors.

Miłosz had occasion to think about Winnie-the-Pooh the year my son was born. In April 1996, he remarked on “the news of the death, at age seventy-five, of Christopher Robin Milne, immortalized in a book by his father . . . as Christopher Robin.” In the brief meditation from Road-side Dog titled “Christopher Robin,” Miłosz wrote:

Owl says that immediately beyond our garden Time begins, and that it is an awfully deep well. If you fall in it, you go down and down, very quickly, and no one knows what happens to you next. I was a bit worried about Christopher Robin falling in, but he came back and then I asked him about the well. “Old bear,” he answered. “I was in it and I was falling and I was changing as I fell. My legs became long, I was a big person, I wore trousers down to the ground, I had a gray beard, then I grew old, hunched, and I walked with a cane, and then I died. It was probably just a dream, it was quite unreal. The only real thing was you, old bear, and our shared fun. Now I won’t go anywhere, even if I’m called for an afternoon snack.

He begins in the voice of “old bear” from the house at Pooh Corner. But then the dead boy speaks; Christopher Robin is the poet, come back to reassure us that growing old and dying is probably just a dream, and anyway, he isn’t going anywhere. Probably this is why we cling to what our poets say.

Molly Wesling was an assistant to Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz in the early 1990s. She holds a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures from University of California, Berkeley, and is currently a senior editor at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research in Madison, Wis. This essay was first published in 2015 by Brick and appears here with the author’s permission.

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

Great reprint. Thanks

Beautiful.