Luigi Mangione’s ‘Baffling’ Journey

I’m no William of Ockham, but the simplest explanation—a young man in the throes of mental illness—may prove the best.

By Michael Judge

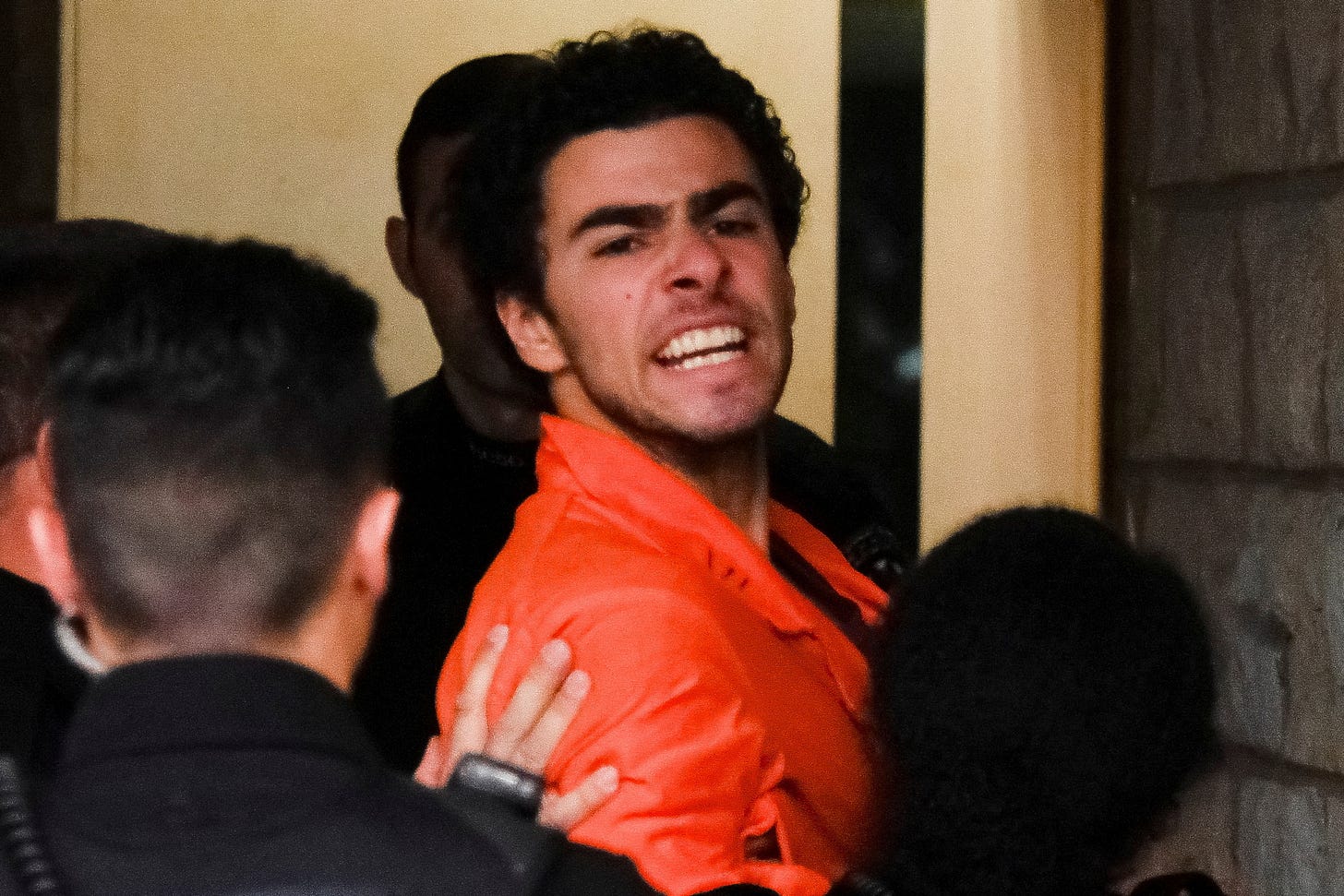

Like most people I know with a loved one who’s suffered from a serious mental illness, I’ve been shocked by the media descriptions of Luigi Mangione—the 26-year-old private school valedictorian and Ivy League graduate apprehended by police Monday and facing murder charges for the shooting death of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson—as “strangely normal” or a young man “on a baffling journey from star student to murder suspect.”

What’s baffling to me—and probably millions of other Americans who’ve seen a friend or family member suddenly commit bizarre, terrifying, and yes, sometimes violent acts in the midst of a psychotic break or paranoid delusion—is how willfully ignorant many in the media seem to be.

It may not be politically correct or ethically sound to speak…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The First Person with Michael Judge to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.