How E.B. White Saw It All—A City, Its Future

On E.B. White's birthday, TFP revisits the great American writer's prophetic essay, "Here Is New York."

FROM THE ARCHIVES

The Wall Street Journal, Aug. 16, 2002

By Michael Judge

The Wall Street Journal is about to return in full force to its editorial offices in the World Financial Center. Just across the street is an immensely empty space where I used to buy my lunch, do my banking, have my shoes shined, buy Christmas and birthday presents—and at least once a day stare up at 110 stories in wonder.

E.B. White understood that the idea of New York, this "capital of everything," was a threat to dictators and religious fanatics the world over. "In the mind of whatever perverted dreamer who might loose the lightning," he wrote, "New York must hold a steady, irresistible charm."

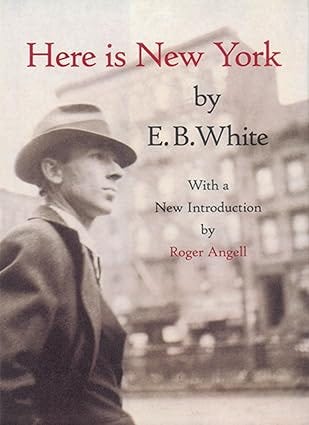

Lying in bed the other night, I reached for a book to take my mind off the day's headlines. I decided on an essay by E.B. White called "Here Is New York." I'd read it years ago and looked forward to being carried away again by the graceful prose and elegant insights of the longtime New Yorker essayist and author of such beloved children's books as "Charlotte's Web" and "Stuart Little."

The first paragraph did the trick. I was instantly transported back to the New York of 1948 and found myself agreeing with White that "no one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky." Writing from a "stifling hotel room" in Midtown, he felt the electricity of Manhattan surge through him. "The city is like poetry," he wrote. "It compresses all life, all races and breeds, into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal engines."

But before long the essay grew dark, the author increasingly uncomfortable with the changing rhythms of New York's "poetry." These were the postwar years, the years of big cars, big dreams and American supremacy on the world stage—the "good old days." But they were also the first and most uncertain days of the Cold War; the Soviets would soon have the bomb, China was in the throes of revolution, and trouble on the Korean peninsula did not bode well.

At the time of White's writing, the atrocities of World War II were still fresh in his memory. Hitler had put a bullet through his head at the end of the war, but not before raping Europe and murdering millions of Jews. Japan's kamikaze pilots had stopped falling from the sky, but only when Truman "unleashed the power of the sun" on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ushering in the nuclear age.

White, a gentle soul with a farm in Maine, had seen the newsreels of the London Blitz, Dresden, the firebombing of Tokyo. He had read the accounts of Holocaust survivors, the poetry of dead soldiers. He had seen a great evil defeated at great cost. And perhaps most important, he knew the struggle was not over.

"This race—this race between the destroying planes and the struggling Parliament of Man—it sticks in all our heads," he wrote. "The city at last perfectly illustrates both the universal dilemma and the general solution, this riddle in steel and stone is at once the perfect target and the perfect demonstration of nonviolence, of racial brotherhood, this lofty target scraping the skies and meeting the destroying planes halfway, home of all people and all nations, capital of everything."

E.B. White was born in 1899; he died in 1985. He never saw the city he loved under attack. But one gets the feeling that he imagined it over and over again. He understood that the idea of New York, this "capital of everything," was a threat to dictators and religious fanatics the world over. "In the mind of whatever perverted dreamer who might loose the lightning," he wrote, "New York must hold a steady, irresistible charm."

Somewhere in the years between White's death and last September we became complacent, confident that we were winning "this race between the destroying planes and the struggling Parliament of Man." The end of the Cold War and the dominance of liberal democracies led some to declare "the end of history." The race, while not won yet, was in the bag.

Now we see that the end of the Cold War was not so much the end of history as the resumption of it. The struggle for freedom continues from Burma to Baghdad. White saw New York as a model for the world, calling it "a permanent exhibit of the phenomenon of one world." An early convert to "internationalism," he declared the first United Nations meeting "a carnival of hope." His embrace of "world government," while dangerously naive in my view, betrayed his sincere belief that "our interests are other people's—and theirs ours."

The ravages of the war changed New York for E.B. White, much the same way that one clear morning in September changed the city for me, along with millions of others. Yes, there is a hole in Manhattan's skyline, which will be filled over time. Yet the city remains, as White once beautifully wrote, "what the white church spire is to the village—the visible symbol of aspiration and faith, the white plume saying that the way is up."

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

I have a copy of White’s Elements of Style I used to read through pretty often.

This article is beautifully written, Judge.

Thank you, Michael.