Deborah J. Stein: Letters From Ruthie

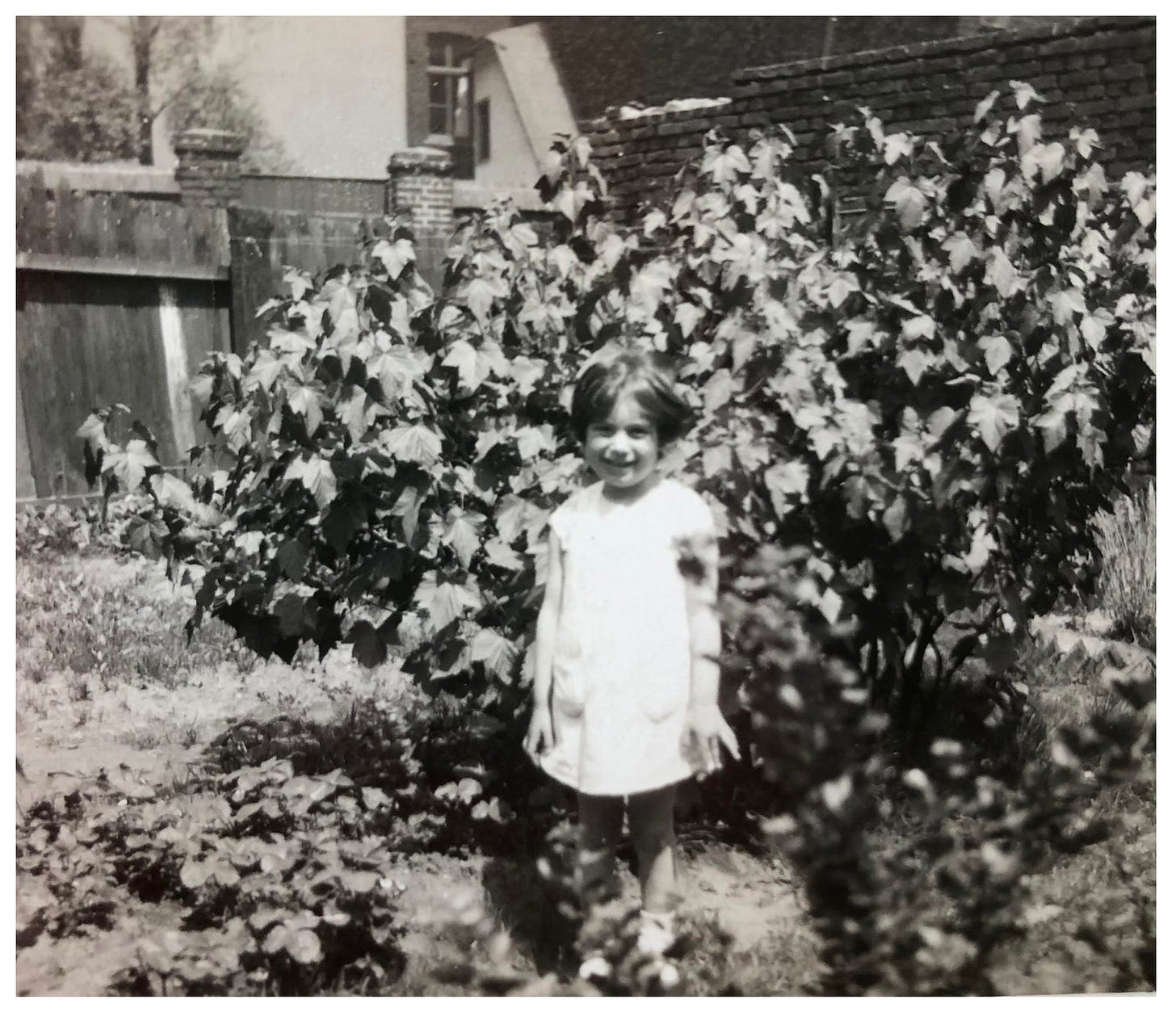

As the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Dachau approaches, TFP proudly revisits Deborah J. Stein's lyrical essay for her mother, Ruth Stein, who fled Nazi Germany in 1937 at the age of 12.

By Deborah J. Stein

I try but shut the door still on my mother’s final purse, her nightgowns, her lower-lumbar pillow, the last perfume bottle I gave her—a smell which sends out her ghost, the reminders that a woman who was a mother once walked, slept, smelled strongly of sweet powder in the morning, existed.

This last thing found and re-found, a letter my mother began, the last letter. The last letters:

H. I. M. A. G. I.

I t ' s a

It’s a

Maybe it was a nice day. Maybe it was a rainy day. Maybe it was a skilled day. Maybe it was a red day. Maybe it wasn’t her day. A lonely day. The dullest day. A day like none other. Maybe it was a

Hi M A G I,

She left the E off Magie—the A looked troubled in its creation. Magie is my mother’s cousin so is my cousin. Maybe my mother asked the attendant to tell her how to spell Magie and maybe the attendant guessed. She stopped at “I” when the attendant had a walkie-talkie message about Mr. Bernstein in Room 234 who did not want to wear pants today. It’s a day like: the job of “attendant” shifting and changing over the days and months my mother was locked in her small barely finished being furnished room, the room that became her cell, her brain that became a jail, her brain that would let down its long golden hair out a window which we would stand beneath and wave to her while talking on the phone with her, the phone she forgot how to use, the wave she forgot how to use, as my mother lost her writing.

It’s a: day to end all days M A G I because from this letter forward I will no longer write or know what to do with a pen or know what to do with a pencil or remember the alphabet or remember the possibilities in the constellation between my head and my hand and I cannot seem to use my hands to change the mucky water in the flowers which are slipping away from me behind this chair M A G I, the chair that somehow was in my house and now is here in this cell and I am sitting in it M A G I. My dignity M A G I. This hand won’t ever again pick up my phone book and dial my daughter’s phone number again and I will never again know how to leave her a message and never again will I say, “Debbie?…….Where are you? You’re never home…Ok well…….… Call me sometime if you ever get home god forbid. I need to ask you a question….Ok…..bye.” Well, M A G I I am always home. I’m here in a place I don’t understand. They dumped me here M A G I. Tell Debbie take me home.” I’m a prizener. I’m a prisoner M A G I. It’s a P R I S O N. With love, Ruthie It’s a

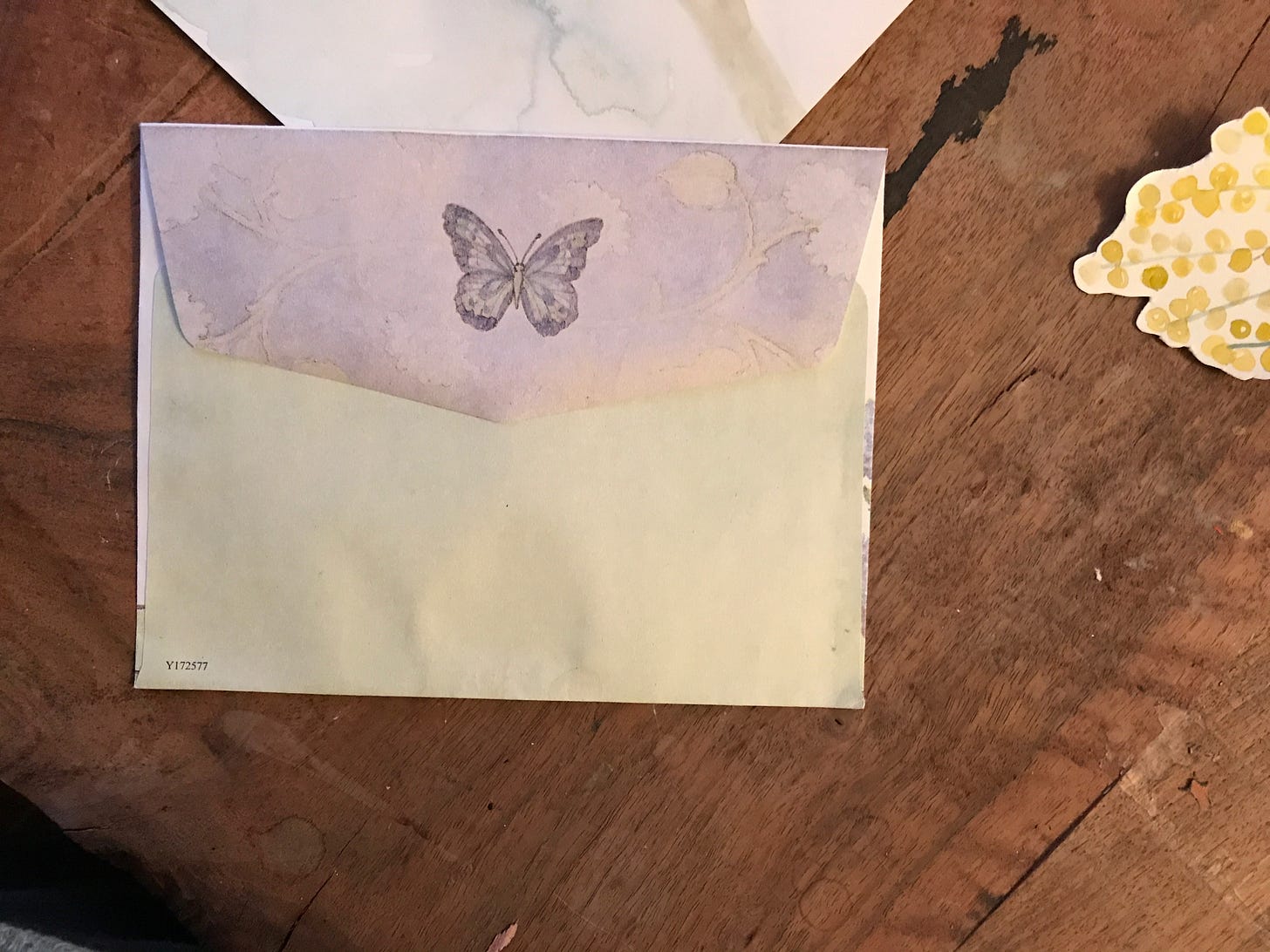

letter my mother Ruthie wrote, not on a proper piece of stationary, which my mother Ruthie would have wanted, of which I had dropped off plenty and I’d found drawers full from Easter Seals and other charities that would send her envelopes she’d put $15 in their envelopes and they would send her envelopes but Ruthie began her letter on an envelope with a picture of a butterfly on the flap, a butterfly who might have sworn the struggle of metamorphosis was worth just one day of flight, one day to love.

My mother went into assisted living on March 7th 2020.

My mother turned 95 on March 14th 2020.

On March 14th, 2020, her 95th birthday, all elder care facilities in NY State locked down.

No one knew what to do so we brought cake to the window while the world flipped a switch.

We did not see my mother again for

It’s a story maybe

Maybe this letter was practice for the real letter which she would have gotten to if lunch hadn’t come and if lunch wasn’t set up on a tray put in front of her while she sat in her chair or lunch set up in front of her as she laid in bed and when the attendant came in she had to coax Ruthie, “GET UP!” saying loudly , “COME ON RUTHIE. It’s lunch time dear!” She helped Ruthie up.

Ruthie didn’t want to get up.

Ruthie was tired and left off the E of things.

But the attendant made her EAT, helped her A T, helped Ruthie lift spoons to her mouth until the attendant was lifting spoons to Ruthie’s mouth every lunchtime and sometimes Ruthie had to wait, I’m sure of it, until 3pm to EAT, to A T, until a different attendant who had a minute, could put a spoon of soup, now cold, to Ruthie’s lips as Ruthie grimaced. Or maybe they microwaved it for her and watched as Ruthie made a its too hot face.

Ruthie wasn’t a fan of soup. My father and I enjoyed a plate of soup. Ruthie used to say, You’re just like your father—you both like a hot lunch.

Maybe some days the attendant was tired and then Ruthie just watched the lunch on her tray with disgust. Ruthie might also be stuck with a show on tv that she didn’t like because Ruthie had forgotten the way her hand used to lift a spoon to her mouth, or operate the fork, or make a knife useful and Ruthie lost the remote control which she didn’t know how to use anyway, which I would find finally in a box stuffed with wrinkled clothes with name tags that said RUTH and other odd things like a crayon I’d sent or pictures of my father or my brothers or me.

Become a Free or Paid Subscriber to Deborah J. Stein’s Substack Below

And I’m not sure anyone knew Ruthie liked to watch Ellen at 4 on weekdays, The Bachelor on Mondays, Dancing with The Stars each Tuesday, old movies on PBS on Saturdays, Ruthie would fall asleep perhaps at 6 now, and wake at 9 and again at 12 and again at 3 and again and maybe she learned to turn her brain off and stare at stars which became letters on the ceiling and go back to sleep without books or television or memory or whatever keeps a body in its soul.

Ruthie couldn’t lift a cup of coffee anymore. Ruthie loved a nice cup of coffee. I called once to ask if they could give her more coffee so maybe when we face-timed she wouldn’t fall asleep and they said sure ma’am. I said, please give her coffee so she can see us. Ruthie couldn’t lift the cup.

I still don’t know if they gave her a nice cup of coffee after her lunch. I still don’t know if she ate her lunches. I don’t know if she brushed her teeth. Ruthie slept right through.

Maybe the letter on the butterfly envelope was written to M A G I as she fell asleep dreaming the words It’s a day you shouldn’t know from M A G I. I want to butterfly away.

There was an attendant who helped her shower and dress and that was the attendant she hated. She told me about the shower attendant then she would plead with me through the screen, when the face-time attendant slipped from her room. She’d say, “You have to do something” and I tried to do something but short of kidnapping her which I would have done, wanted to do, was about to do, knew I couldn’t do what could I do? What could I do?

The ghosts would whisper to me like coyotes or wind in the middle of the night the things I knew and we traced points on dream maps of the uncle who made my mother touch him when she was small, the boy who “had his way with her” and was never seen again, the gynecologist who pushed into her with his hand in a way she knew was wrong—when she was no longer a girl, when she’d already had three children— and ancestors who would have had the same fate, and I who would have the same fate, and all the girls and women who would have the same fate and how can I save my mother, how can I save anyone who is trapped on the flap of an envelope, how can I without an E to give them, be a daughter who can't save them or give them the E, without sons or brothers who won’t save them or notice the E, M A G I

how can I salvage this somehow

how can I rid this from them some how can I

stop the uncle, the pharoahs, the nazis, how can I understand this world, how can they, how can I, how can I without them how?

Of known things, it was known my mother had beautiful handwriting. Melodic characters and heartfelt punctuation, absolute were her s’s —unwavering—her m’s a delight. Her confidence here was unquestionable. She told that she came to this country without the right words to communicate so she practiced her English handwriting for months until each form was perfect. She then practiced her flirting and then consolidated them together to write letters to GI’s to support the war efforts, while her brother was back over to work as a German translator for the Dachau liberated. In those years my mother was praised for her beautiful handwriting. Aunt Magie at the zoom funeral: Ruthie had the most beautiful handwriting.

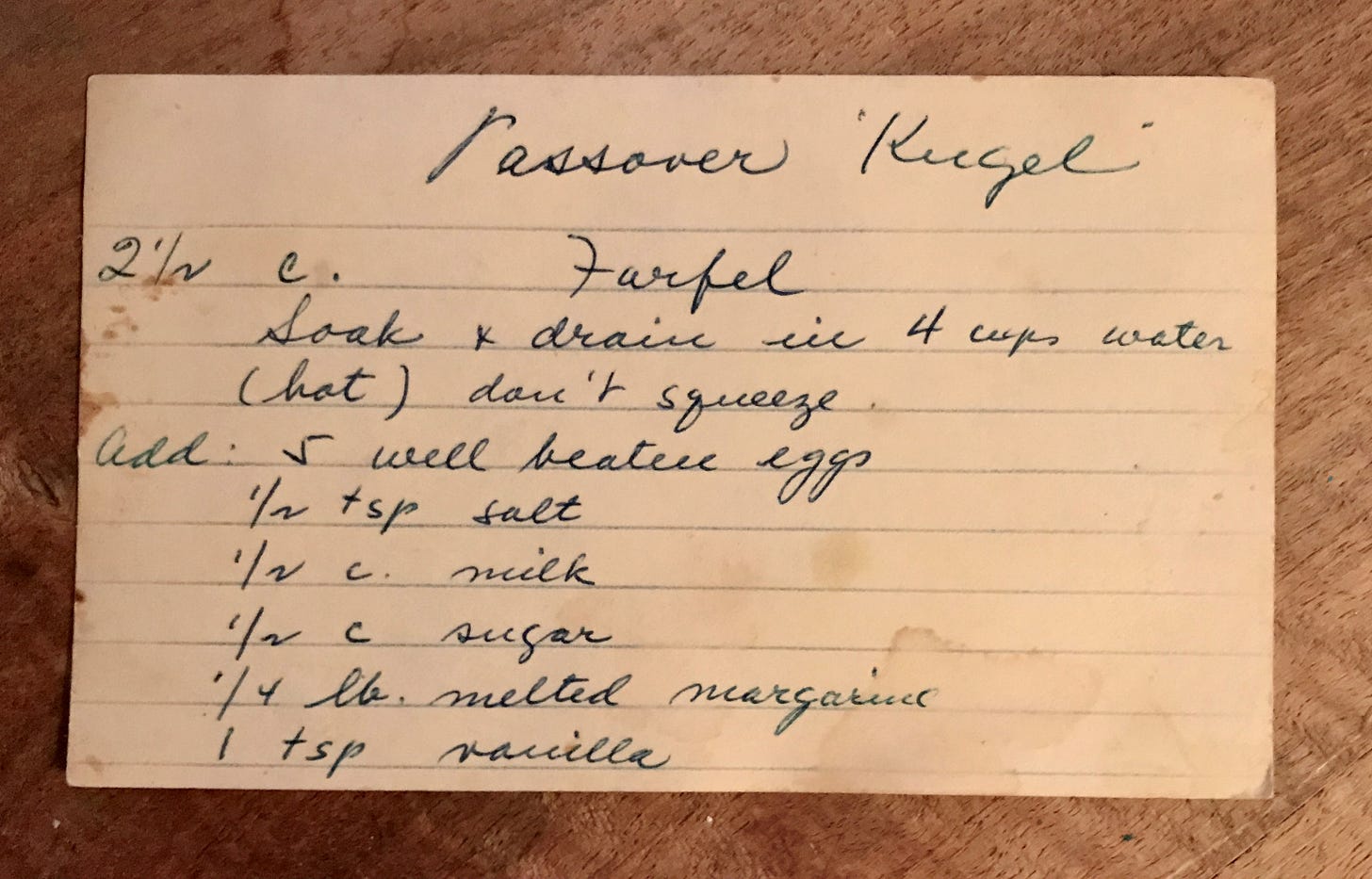

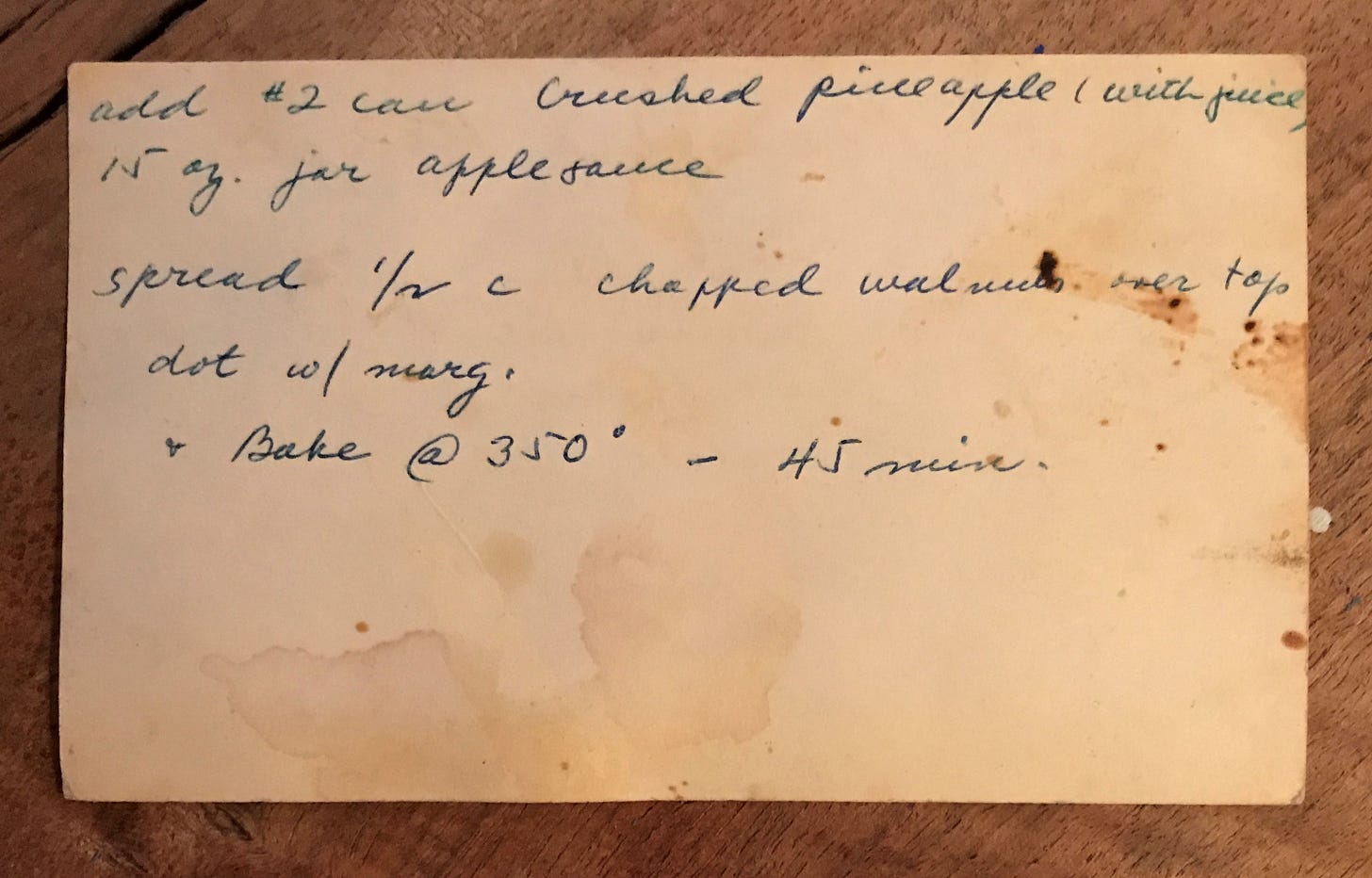

I imagine this recipe was a second draft. The first draft most likely was written on scrap paper near the phone, written during a phone call with her mother, or with a cousin, her one surviving aunt, (Magie’s mother), her sister-in-law, or maybe from a friend who dictated it from the paper.

I don’t remember eating this kugel.

Or maybe I do.

Maybe it was an early Passover, when two families would join together and I would be “the son who had no words at all” and the prayers would be recited by the uncle who translated the world after Dachau, who’d sit at the head of the table behind a shank bone and bitter herbs, who would go on forever, while women quietly lifted out of chairs to check if Oma’s matzah balls had levitated to the top of the soup, the heat of their soup pushing up the knaidlach of our foremothers in the busy small burdened kitchen for days before this day, when on that day a brisket was made with onion soup packets and colorful lime jellies came into the house and possibly this kugel made according to this recipe which was created when a can of pineapple was opened by the effort of hands on a can opener and for a long time I was the youngest and so I would always ask the same four questions as the heat of reading aloud made my neck burn and my father would be devilish and recline on one arm as he read the part of the WICKED Son and laugh, and later I would search for the afikomen, half a piece of matzah my uncle would hide, and I’d look under couch cushions for it and the adults would laugh and say: warmer. cold. freezing cold. HOT… BOILING HOT and these temperatures would help me return the unleavened bread of our forefathers to my uncle for a quarter, a kind of half-time show, and then solemnly, sometime later, in the longest most exciting dinner of the year, I’d also be asked if I wanted the most haunting job of the night, to open the door for the prophet Elijah and I would open it.

Then I’d watch this quiet as the ghost slipped in and drank from the cup of wine and this still didn’t seal the ceremony but was still, my favorite part.

My mother’s favorite part was the singing and the Dyanoos and the coffee at the end and the smell of coffee at the end and the smell of salt and soup and coffee and cream and cake and crumbs and clinking and singing at the end.

All the ghosts would drink from the cup of wine I thought and once I think I heard my grandmother cry and once I think my father drank from Elijah’s cup, and once I think I did, and once before everything else, there were all these great happinesses in remembering all the great sadnesses and the force of imagining the great strength it took to part an ocean to get to the other side.

In the summer of 2020, two young attendants played the little keyboard sent along for my mother while my mother played the harmonica brought to her as well. Those were happy moments for her it seemed, before the days she'd chosen to sleep as long and as much as she could. I made videos but haven’t watched them.

These young attendants showed up to her zoom funeral along with a few others who told us how our mother, their Ruthie, our Ruthie, two different Ruthies, the same Ruthie, lit up their difficult days, how she spoke of us, how it broke their hearts when they knew they could no longer care for her and next she’d need to go to a place with a memory care unit.

Next she was dehydrated when the attendants could no longer watch her every move and so she went to the hospital and I thought I’d arranged for the only rehab that’d allow visitors but there were caveats and when we only saw her twice in the month she was there, as Ruthie might say, we didn’t understand as reached the beginning of the end of this story.

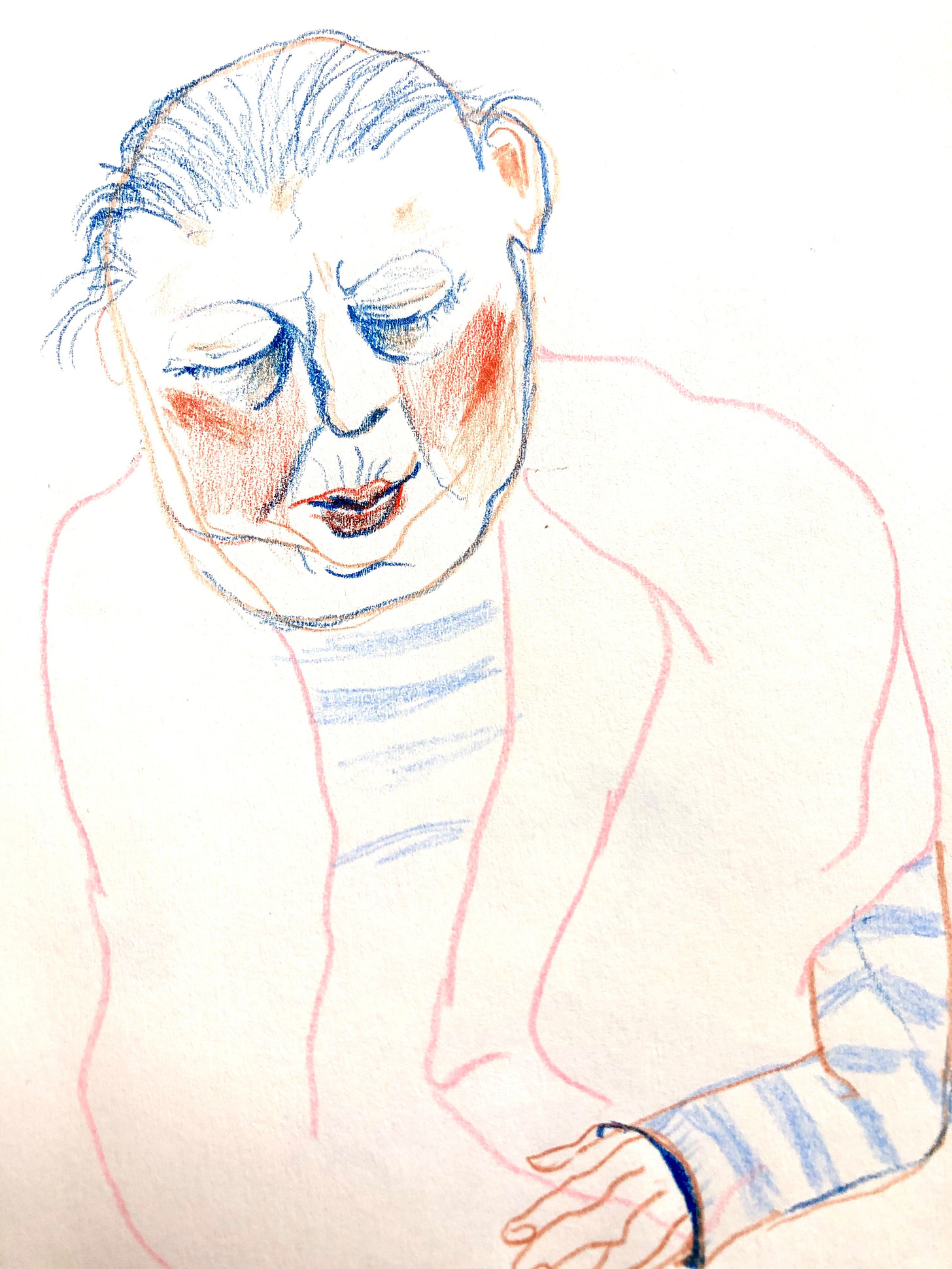

Once I saw her on a cold September day, I took out pencils and my sketchbook and drew her as she slept in a wheelchair in the blue sun.

At the end of what we thought could be still a beginning, the beginning of the beginning of long days of fighting, clenched teeth cracked from grinding, anger and resentments all of which would eventually lift and then drift in the long pause of forgiveness in which we are here now, all of which, as I write this, become a boat coming into port, that I am trying still to send away from my port I write:

My mother ended in a room like a closet at the end of a long hall in a memory care unit in a town we didn’t know, but not far from the apartment house where she lived when she was a girl, a young refugee, a forever immigrant, in Jamaica, Queens around 1940.

Dear M A G I

It’s a

blustery November of 2020 and Debbie got in trouble consistently and made big trouble and made big ocean waves that became tidal waves during my long week of dying, of fighting that oh I was dying, and she wrote rivers of letters that spelled things to bureaucrats to tell them my mother is dying, I was dying.

Love, Ruthie

The hospice nurse Mona and the hospice rabbi Charlie who brought comfort and challah when we met each other on a Friday, masked in the parking lot, told me she looked good, she looked clean, but not even they, not she not he could help me to see her, only I could help me to see her and so

I helped me by becoming a different person and becoming

the building where she’d die and becoming

the room as she died, and becoming

pictures on the walls and music in her ears and as she groaned in passage,

we didn’t die alone and I felt human and whole again and I feel

back in my body again and I feel

sort of like our souls got to touch again and I

want that again

so I go looking for it again and again and here I am still in this same still place

and here

is some other love and here is that love still here is some kind of thing that feels

like it

I found

Deborah J. Stein, publisher of the Substack Sometimes a Ghost, is an artist and writer from New York City and New Mexico. She teaches visual narrative workshops and holds creative residencies twice a year. She is working on her first children’s book. For more information please visit her website at www.deborahjstein.com. Deborah’s mother, Ruth, and her uncle, Curt, were resettled in America with the help of the refugee agency HIAS. For more information about the history of HIAS, see TFP’s interview with HIAS President Mark Hetfield.

TFP IS A PROUD MEMBER OF THE IOWA WRITERS COLLABORATIVE

Deborah, thank you for this important piece and testament to love, fragility, and endurance. 🙏 I’ve read these lines to you before, but they seem more crucial with each passing day. They’re from the great Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, and his timeless poem The Envoy of Mr. Cogito:

go upright among those who are on their knees

among those with their backs turned and those toppled in the dust

you were saved not in order to live

you have little time you must give testimony

be courageous when the mind deceives you be courageous

in the final account only this is important

She needs to write a book and I would devour every word .