Dear Etheridge

A letter to the poet Etheridge Knight on the 32nd anniversary of his death.

By Michael Judge

Dear Etheridge,

I can still hear your cracked baritone booming, feel your words and rhythms living, your humor, grief, love, and regret tearing through the room. I was 24; you were 59, just three years older than I am now. It was a clear autumn night, the kind that comes on quick and gets colder till daybreak.

You’d stopped treating your cancer by then, so you and your companion—“my lady,” you called her, “my love”—the poet Elizabeth Gordon McKim, could tour the country together singing your poems and stories and wisdom, breathing in and out together in the last months of your life.

Sometimes the wounds are so deep you have to sing yourself alive.

Elizabeth told me that you two met in Memphis in 1978 and never stopped loving each other—despite the illnesses, the addiction, the cancer, the car that ran you down and tore you up in Indianapolis before you died in her arms, in your home, where you belonged, on March 10, 1991, 32 years ago today.

My teacher, your friend, Gerald Stern arranged the reading that night, Oct. 21, 1990, on the campus of the University of Iowa, home to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The venue was huge for a poetry reading, overflowing with writers and students and poets and activists and, yes, even academics. It was more an event than a reading, more John Lee Hooker than Langston Hughes. Like Orpheus, you journeyed to hell for the ones you loved, and your voice convinced even Hades that they belonged with you among the living.

Sometimes the wounds are so deep you have to sing yourself alive.

“I first defined myself as a poet when I was in prison,” you said. “I went to prison in 1960 for armed robbery. I was hooked on drugs, and I snatched a money box from a woman. I was sentenced to 10 to 25 years. And I one time lived above death row.” That part was true.

But the joke that followed, delivered perfectly by you, was about a series of botched electric-chair executions, and how the final guy to be executed—a college graduate—thanked his family and said his goodbyes before pointing to the electric chair and saying, “And if you hook this red wire to this yellow one, this thing will work!” When the audience burst into laughter, you explained, “So that’s education.”

When the laughter died down, you said, “I’ll say some poems to you that I first made up, early on, when I was in prison. The first one was titled ‘Genesis’”:

Genesis

the skin

of my poems

May be green, yes,

and sometimes

wrinkled

or worn

the snake shape

of my song

may cause

the heel

of Adam & Eve

to bleed . . .

split my skin

with the rock

of love old

as the rock

of Moses

my poems

love youFrom then on you delivered line after line that tore us up, hit us in the belly, and made us think with our heart. Each poem a confession and condemnation, you sang of suicide and rape in prison, poverty and genocide in the Black community, corruption and violence in the “greater prison” of America, and love with no end.

You sang these lines from “A Wasp Woman Visits a Black Junkie in Prison”:

After the seating And the greeting, they fished for a denominator, Common or uncommon; And could only summon up the fact that both were human.

I sat on the floor to your left, along the wall, just behind the podium, so I could see you rubbing your belly under your sweater from time to time between poems. You walked with a limp from the car that hit you back in Indianapolis, your wounds from that final violence not fully healed. You’d stopped chemo for the cancer that was eating your lungs and killing your body so you could go on the road and read with Elizabeth.

Sometimes the wounds are so deep you have to sing yourself alive.

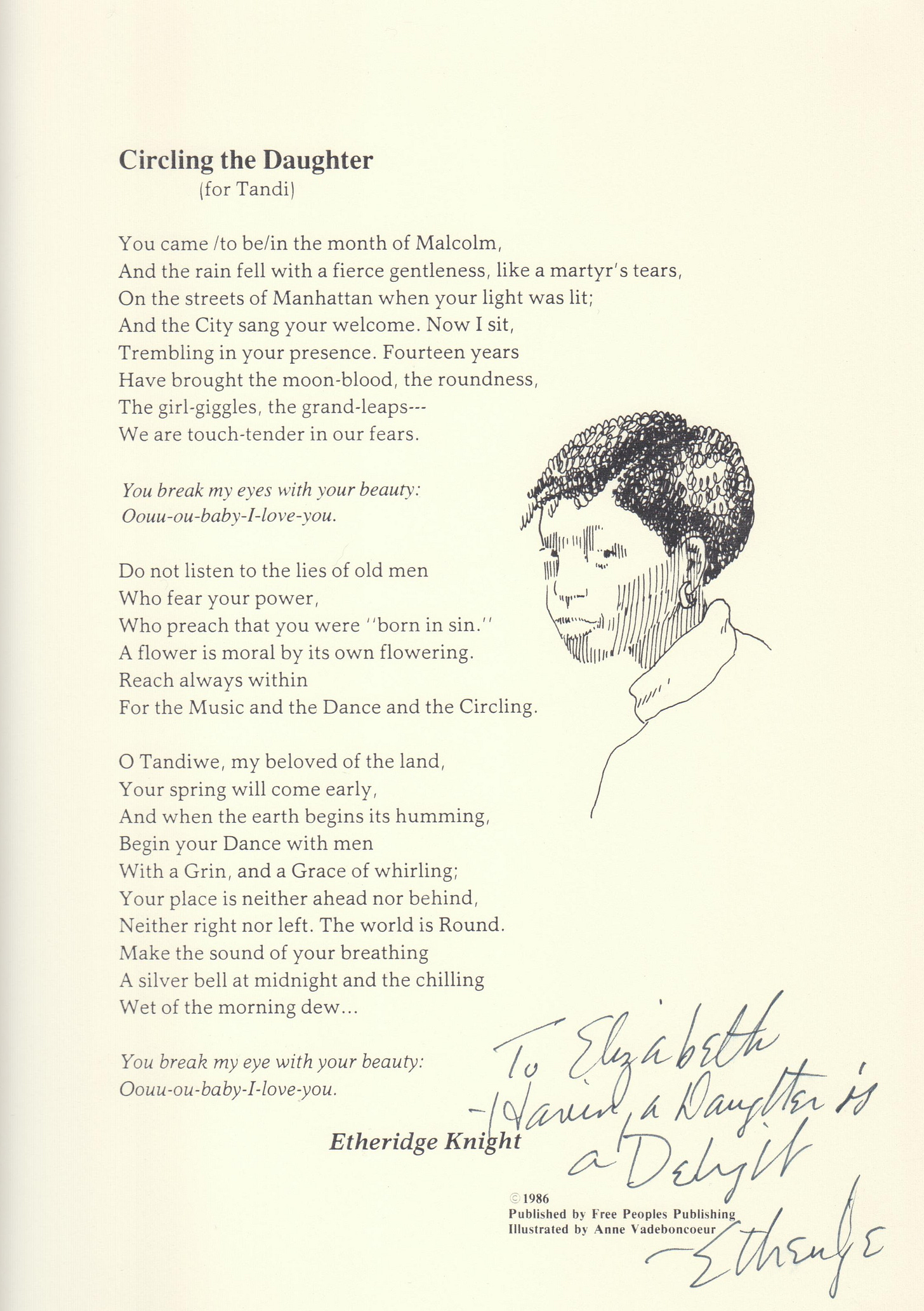

The last poem you read was a late one called “Circling the Daughter (for Tandi).” In your introduction, you explained “That’s my daughter. She’s 22 now. I made up this poem when she was 14. When I separated from her mother she was 10. And I didn’t see her from the time she was 10 until she was 14. And when we met she was hostile at me. She thought I had abandoned her. And when we met we both wanted to embrace each other, but we both were scared. So we started circling like two little boys fighting, you know, going round and round. So I titled the poem ‘Circling the Daughter (for Tandi)’.”

When you got to the lines—A flower is moral by its own flowering. / Reach always within / For the Music and the Dance and the Circling—you broke down, your baritone cracking further, breaking.

But you continued—you read with the strength and tenderness of a father reading to his child, soothing her nightmares, giving her hope. I remember the poet Jorie Graham, usually a picture of composure, in the front row, tears flowing.

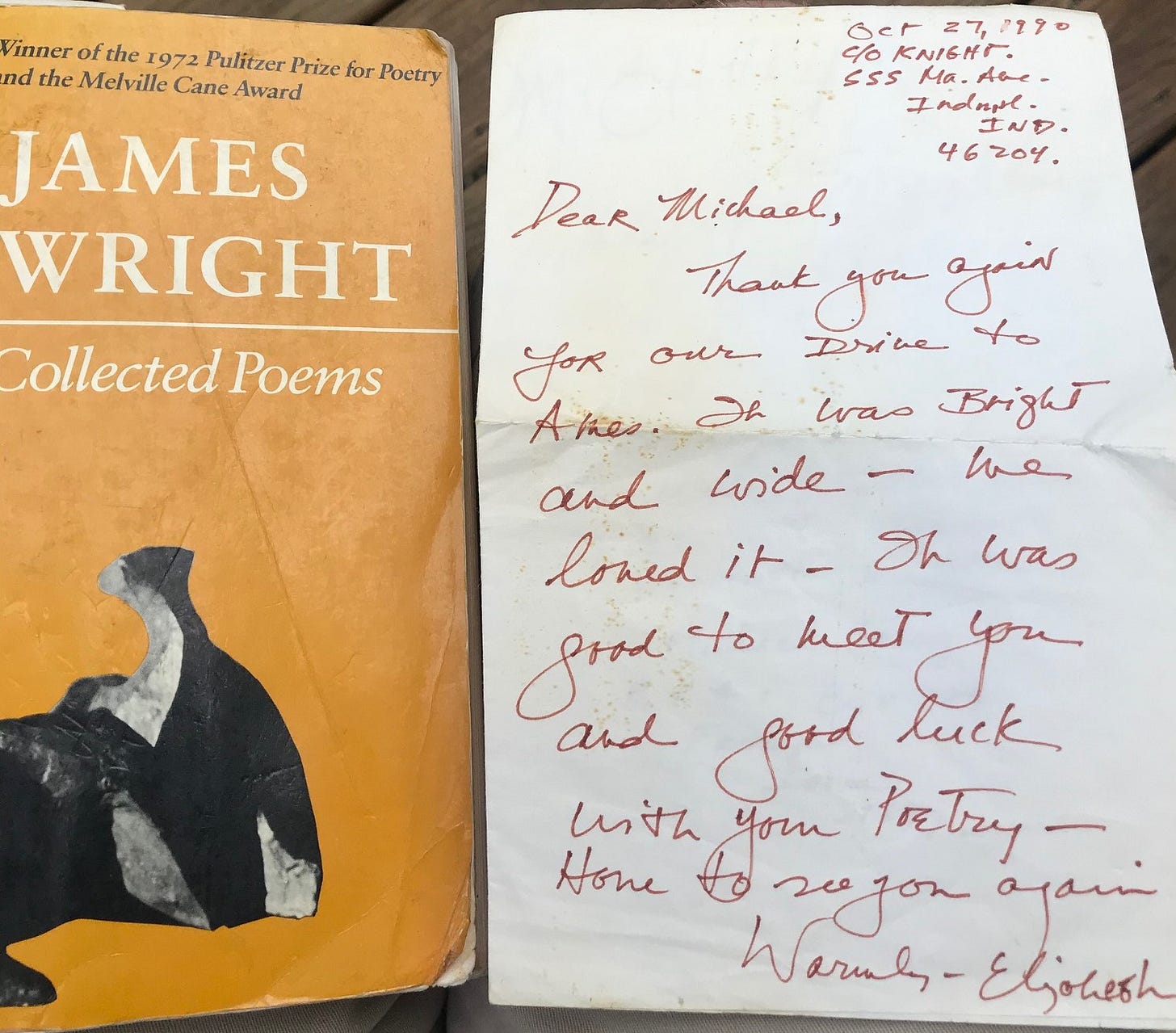

Gerald introduced me to you and Elizabeth immediately after the reading. In a workshop a few days before, he’d asked the class if anyone had a car and would drive you to your next reading in Ames, Iowa, about 130 miles away. I volunteered and was thrilled to meet you both that evening.

You were tired, you said, and had to get some rest. “See you tomorrow,” you said. “10 a.m. Don’t be late—or early.” It was overcast the next morning but the sky turned blue as the day warmed. You insisted on Elizabeth taking the front seat next to me in my tiny, beat-up Nissan Sentra, and squeezed into the back, one foot behind each chair, your knees nearly touching the ceiling.

You asked who I was listening to on my Sony cassette player. “The Clash,” I replied. “Michael-Man,” you said, “do me a favor, if you could. Pop this tape in there, it’s Coltrane—ever heard of John Coltrane?—it’s live, a bootleg.” As Coltrane’s music poured out and became my favorite on earth, we talked about the cold of the Midwest, how we hated it, the gray and brown and yellow of the plowed fields, how we loved our fathers but lived too far from them most of our lives.

I remember an image from your memory—is it yours or mine?—of your father at the top of the stairs, and you far below, before you faked his signature and went to war in Korea, where you were “blown up, then shot up with morphine” and sent home in 1951 with a habit that lasted a lifetime.

I brought a James Wright book of poems and you read “Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio.” You told me how Wright, one of my heroes, was your friend, and how you visited him in the hospital in New York City in 1980 before he died of tongue cancer and he asked you to move closer so he could whisper in your ear, “I’m dying . . . I’m dying . . . for some ice cream.”

I don’t think I told you, but back then I was struggling to survive the loss of my older brother John to suicide and my oldest brother Steve to schizophrenia. Both had suffered terribly—as had my entire family—and the only thing that eased the suffering, or at least helped me endure it, was poetry.

Sometimes the wounds are so deep you have to sing yourself alive.

That’s a truth you knew in your bones. To paraphrase Auden, “Mad America hurt you into poetry.” I was lucky. I came from a white Midwestern family and—after a few run-ins with the law that got me thrown out of high school—attended a state university where I was lucky to stumble into a classroom that not only taught poetry, but where I was surrounded by living, breathing writers.

You weren’t as lucky. Born in Corinth, Miss., your father struggled as a farmer before moving his family to Paducah to work as a laborer on the Kentucky Dam. You had six siblings and the family struggled to make ends meet. You ran away from home often, and dropped out of school early, hanging in juke joints and poolhalls and eventually joining the Army at 17. You served as a medic in Korea, where you sustained shrapnel wounds and got shot up with morphine.

After an honorable discharge, you moved to Indiana where you struggled to support yourself and your addiction. In 1960, you were convicted of robbery and began serving a 10- 25-year sentence at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City. The trauma of being incarcerated was so great, you said, that you hardly remembered your first weeks and months behind bars. Later, you famously said, “I died in Korea from a shrapnel wound, and narcotics resurrected me. I died in 1960 from a prison sentence and poetry brought me back to life.”

Sometimes the wounds are so deep you have to sing yourself alive.

When we all arrived in Ames, I pulled over to ask a college kid how to get to the student union where you and Elizabeth were to have a Q&A later that afternoon. The kid—white, with an army jacket on—looked in the back of the car and said to you, excitedly, “You’re Etheridge Knight, aren’t you? The poet!” You didn’t miss a beat: “You’re a poet. I’m a poet. We’re all poets, man.”

The Q&A was held in a lounge-like area where you could drink and smoke. You and Elizabeth sat on a stage surrounded by small tables and students nursing beers and cokes. When it started, you asked me to get you a beer and to light a Camel I had given you earlier.

Once you lit up, you called on a student waving his hand in the air. “Why do you write poetry?” he asked. Your response: “P-U-S-S-Y,” enunciating each letter with care and precision. “Why do I write poetry? P-U-S-S-Y,” you said again with a grin. “Pussy.”

The audience dropped their jaws, and pens and pencils. Elizabeth laughed and put her arm around you, knowing you were, above all else, a troubadour, a poet of passion and love. Political correctness wasn’t an option. For you, the muses whispered in your ear, and you whispered, sang, and hollered back:

Fuck Coltrane and music and clouds drifting in the sky fuck the sea and trees and the sky and birds and alligators and all the animals that roam the earth fuck marx and mao fuck fidel and nkrumah and democracy and communism fuck smack and pot and red ripe tomatoes fuck joseph fuck mary fuck god jesus and all the disciples fuck fanon Nixon and malcolm fuck the revolution fuck freedom fuck the whole muthafucking thing all i want now is my woman back so my soul can sing

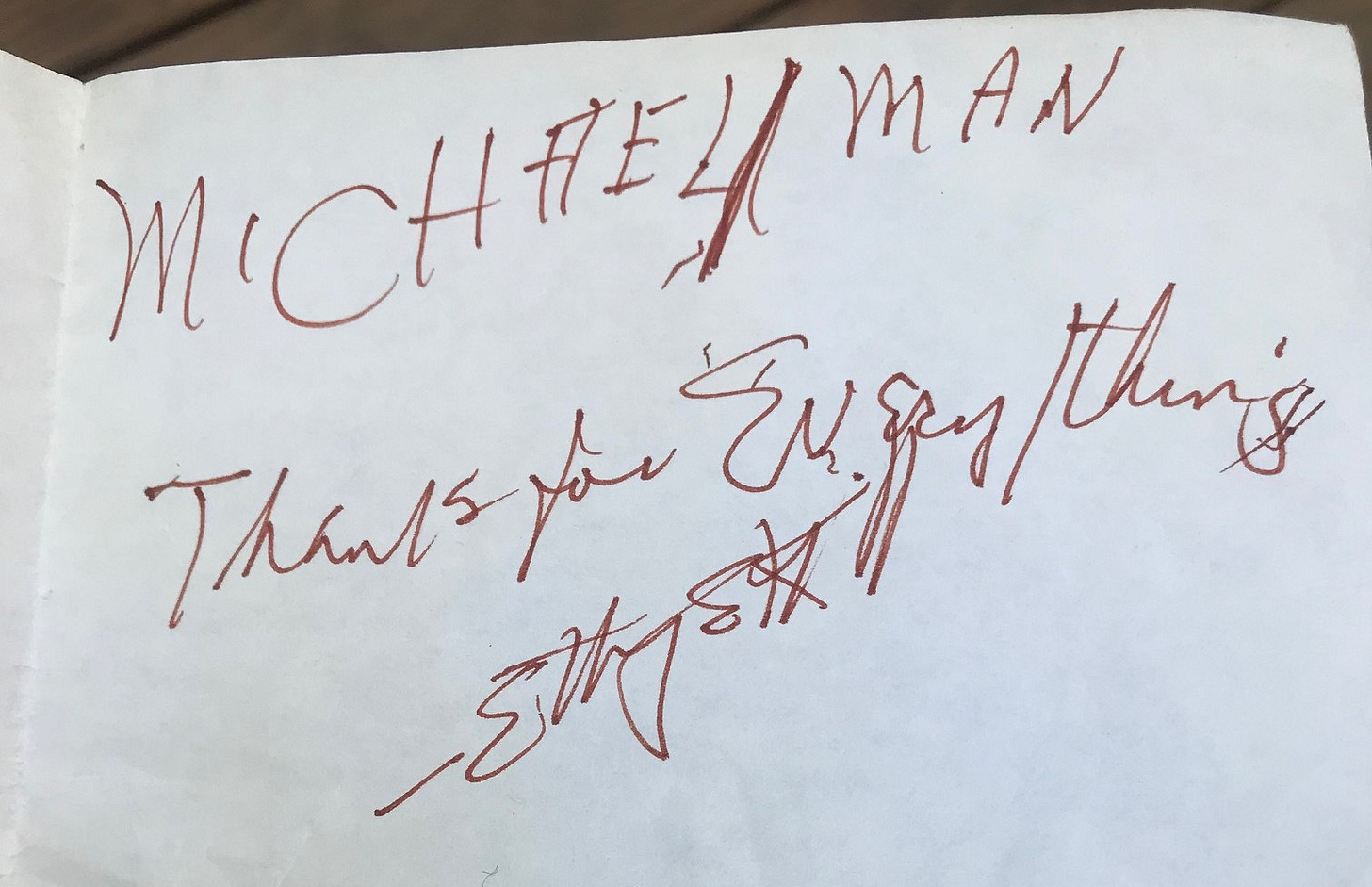

That night, at a Black church in Ames, you and Elizabeth killed it again, as I watched and listened and cried from the audience. When the reading was over, you were swarmed by fans and worshippers. Still, you made your way to me to say goodbye. When one of the parishioners asked, “Etheridge, what you doing with some white boy?” You smiled and said, “That’s not some white boy. That’s Michael-Man.” And then you put your hand on my arm, leaned in close, and whispered, “You still got that little bottle of whiskey in your jacket?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Give it to me.”

“Right now?”

“Yeah, Michael-Man. Right now.”

I reached into my pocket and handed you the flask I’d been sipping from all day. It was about half gone. You untwisted the cap, tilted your head back, and downed most of what was left.

The folks in that church let out a gasp, some laughing, others tsk-tsking. You didn’t care. “Thanks for everything, Michael-Man,” you said, handing me back the bottle. “You take care.”

And before I could put it back in my pocket, you gave me a hug—a great embrace of love and sorrow and farewell, like you were saying goodbye to the world.

Good god Michael, this is extraordinary. It feels like the world moved through you in it’s making. A tribute to the man and the tenderness he showed a young you, a meditation on the coming back, the empathy for the near impossibility but modeled possibility of that, a tribute to why keeping your humor matters as principle, an incantation to building a world and a bridge to growing further rather than up. I love how you call back the one line, the writing as healing, throughout. I will read this again and again. Thankful for you and this space.

Raw and not “my cup of tea” but honest and hard hitting. I respect that.