'Coming Up for Air' at the Close of 2024

Written a decade before "1984," Orwell's darkly comic novel speaks to today's claustrophobic environment of commercialism, propaganda, and war.

Dear TFP Readers,

In the waning days of 2024, I’m lifting the paywall on this piece first published in April 2022 when TFP was just getting started and had far fewer subscribers. Cheers, and a happy New Year to each and every one of you. Here’s hoping you can, if only for a few days, do as Orwell writes in Coming Up for Air and “Stop chasing whatever you’re chasing! Calm down, get your breath back, let a bit of peace seep into your bones.”

—MJ

By Michael Judge

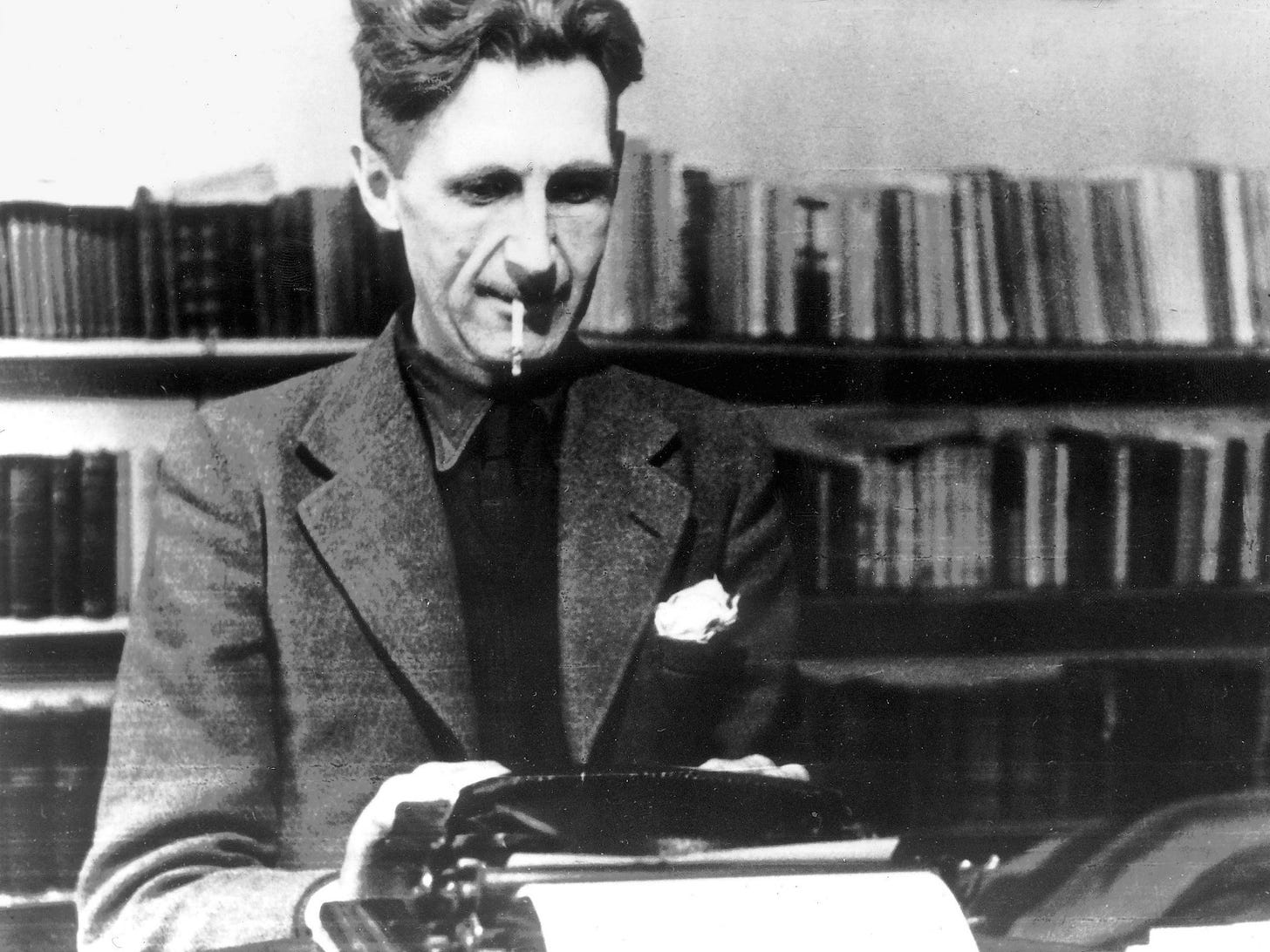

The past years have furnished many depraved moments to remind us of George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language,” none more so than Vladimir Putin’s murderous assault on Ukraine and truth. “Political language,” wrote Orwell, “—and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists—is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

Putin has been trying to make murder respectable for some time now. But his statements that his war on Ukraine is being waged to “protect people who have been abused by the genocide of the Kyiv regime for eight years” and that his goal is “the demilitarization and de-Nazification of Ukraine” are as grotesque and absurd as anything Orwell invented for his fictional totalitarians.

Most are familiar with Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, published in 1949, in which Winston Smith questions the Party’s official slogan: “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.” But what the current environment in the U.S. and Europe most reminds me of is a lesser-known Orwell novel, Coming Up for Air, published in June 1939, a few months before Hitler invaded Poland.

The book isn’t set in some nightmarish future but in interwar England, and centers on one George Bowling, an insurance salesman who describes himself as “a fat man of forty-five” with a “red face and boiled blue eyes.” The shallow commercialism of suburban England is closing in on Bowling, as is talk of war and the ever-present propaganda of the time.

Having just been fitted with new false teeth, he decides to escape it all and return to the fishing hole of his youth in Lower Binfield, a rural village, forgotten by most, west of London. Before departing, Bowling attends a lecture by a “well-known anti-Fascist” a “little chap of about forty, in a dark suit, with a bald head which he’d tried rather unsuccessfully to cover up with wisps of hair.” Like so much of Orwell’s work, it seems to capture the ugly tone of today:

It’s a ghastly thing, really, to have a sort of human barrel-organ shooting propaganda at you by the hour. The same thing over and over again. Hate, hate, hate. Let’s all get together and have a good hate. Over and over. It gives you the feeling that something has got inside your skull and is hammering down on your brain . . . I saw the vision that he was seeing. And it wasn’t at all the kind of vision that can be talked about. What he’s saying is merely that Hitler’s after us and we must all get together and have a good hate. Doesn’t go into details. Leaves it all respectable. But what he’s seeing is something quite different. It’s a picture of himself smashing people’s faces in with a spanner. Fascist faces, of course. I know that’s what he was seeing. It was what I saw myself for the second or two that I was inside him. Smash! Right in the middle! The bones cave in like an eggshell and what was a face a minute ago is just a great big blob of strawberry jam. Smash! There goes another!

This is what so many of us are today so aware of and trying desperately to escape, or drown out. As in Bowling’s world, the rise of nationalism and xenophobia—fueled by mass migration, propaganda, poverty, war, famine, and the mind-splitting pace of technological and social change—have encouraged many of us, whether in person or online, to “get together and have a good hate.”

When Orwell wrote Coming Up for Air, Europe was hurtling toward the war that came two decades after “the war to end all wars.” He, unlike his protagonist, was too young to fight in World War I, being just 15 when the war ended on Nov. 11, 1918. But Orwell had seen a preview of the next great war when, in 1936, at the age of 33, he moved to Franco’s Spain “to join the militia to fight against Fascism.”

Unlike the “little lecturer,” Orwell had witnessed firsthand the corruption of the Spanish Republican movement by Stalinist ideology and brutality. As he wrote in Homage to Catalonia, a masterful memoir of his time at the Spanish front: “All the war-propaganda, all the screaming and lies and hatred, comes invariably from people who are not fighting.” Bowling, like Orwell, had not just studied but engaged in war and understands, unlike the “little lecturer,” the unspeakable ugliness of the endeavor.

War! I started thinking about it again. It’s coming soon, that’s certain. But who’s afraid of war? That’s to say, who’s afraid of the bombs and the machine-guns? ‘You are’, you say. Yes, I am, and so’s anybody who’s ever seen them. But it isn’t the war that matters, it’s the after-war. The world we’re going down into, the kind of hate-world, slogan-world.

It is for these reasons that Bowling longs to return to the hometown of his youth, to the one thing that he can remember that gave him true happiness—fishing. This is not merely nostalgia, but a desire to return to a kind of quietness—a simpler time and place, a sought-after solitude where nature can be reflected upon and the soul nourished.

Seeing a patch of primroses on the side of the road, he pulls over to have a look and perhaps even pick a few for his wife, Hilda:

I was looking at the field, and the field was looking at me. I felt — I wonder whether you’ll understand. What I felt was something that’s so unusual nowadays that to say it sounds like foolishness. I felt HAPPY. I felt that though I shan’t live for ever, I’d be quite ready to . . . I know it’s a good feeling to have. What’s more, so does everybody else, or nearly everybody. It’s just round the corner all the time, and we all know it’s there. Stop firing that machine-gun! Stop chasing whatever you’re chasing! Calm down, get your breath back, let a bit of peace seep into your bones. No use. We don’t do it. Just keep on with the same bloody fooleries. And the next war coming over the horizon, 1941, they say. Three more circles of the sun, and then we whizz straight into it.

As Bowling is experiencing happiness with the primroses, a car comes up the road, and a wave of self-consciousness crashes over him. His embarrassment at being caught appreciating solitude, the beauty of nature, or, as Bowling puts it, “a bit of peace,” is the true tragedy of Coming Up for Air, and, I believe, of our time as well:

I suddenly realized what I was doing — wandering round picking primroses when I ought to have been going through the inventory at that ironmonger’s shop in Pudley. What was more, it suddenly struck me what I’d look like if those people in the car saw me. A fat man in a bowler hat holding a bunch of primroses! It wouldn’t look right at all. Fat men mustn’t pick primroses, at any rate in public. I just had time to chuck them over the hedge before the car came in sight. It was a good job I’d done so. The car was full of young fools of about twenty. How they’d have sniggered if they’d seen me! They were all looking at me — you know how people look at you when they’re in a car coming towards you — and the thought struck me that even now they might somehow guess what I’d been doing. Better let ’em think it was something else. Why should a chap get out of his car at the side of a country road? Obvious! As the car went past I pretended to be doing up a fly-button.

To prefer being thought of as pissing on primroses rather than appreciating them is very, very sad. And not just because it’s masculine foolishness at its worst, revealing of an insecurity that a fat, middle-aged insurance salesman might possess in spades. It’s tragic because it contributes to the opposite of “peace,” a willful denial and debasement of the connections that nourish our inner sense of self, making us human.

Bowling experiences an epiphany only—quite literally—to piss all over it. Why? Shame? Pride? Stupidity? I think Orwell would call it cowardice; the kind of cowardice that ends with one pulling a trigger or firing a missile because one was “just following orders.” In other words, it’s not just truth-denying propagandists and nationalist appeals that feed a frenzy for war. Our broken promises to ourselves and the primroses on the side of the road are just as damaging.

No doubt, like many of you, reports of Russian soldiers boasting about a “safari” hunt for children in Mariupol, and shooting a little Ukrainian girl in the legs—“just for fun,” to watch her suffer—turned my stomach. How do people arrive at such a depraved state? Yes, as Hitler and his henchmen showed the world, racism, propaganda and a hideous union of church and state can reduce children to vermin in the eyes of even the most “upstanding” citizens.

What Orwell tells us in Coming Up for Air is that our epiphanies are our true guides in a world gone mad. Each betrayal of “the most delicate and evanescent of moments” is another building block for brutality, fascism and totalitarianism. Orwell, who had fought fascists (indeed, was shot in the neck by one in Spain) understood how willful detachment and political propaganda designed to desensitize us from the suffering of others lead to collective murder, otherwise known as smashed faces, strawberry jam—war.

Posted just in time for my lunch break. Perfect food for thought. Thanks.