The Writer Across the Table

Acting like a potted plant versus making foolish remarks around one's literary hero.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“It’s Borges, of course,” she said, as though Borges always came into the Runcible Spoon. Indeed, Borges was walking slowly up the path to the coffeehouse, led carefully by a young woman.

I sat near the front window of a coffeehouse I frequented called the Runcible Spoon, reading a book by my favorite author, the Argentinean Jorge Luis Borges. Labyrinths. Perhaps this was my third time through the book. The story I was currently rereading, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” involved an author whose life project was to write a book that had already been written, Don Quixote. The story, like so many of Borges’s, involved conundrums and puzzles, and was loosely based on the paradox of an infinite number of monkeys banging away on an infinite number of typewriters for an infinite number of hours. Eventually, the idea went, the monkeys would write all the great works of literature. Pierre Menard, monkey-like, wanted to write Don Quixote. Not rewrite it or copy it but write it as Pierre Menard. But in his lifetime, he was only able to write one chapter of the classic. The narrator of the story, a friend of Menard’s, compares in a perfect deadpan two paragraphs from the original Quixote and Menard’s Quixote. Of course, they’re identical, but at the same time they’re not because one was written by a seventeenth-century Spaniard and the other was written by someone from the vantage point of the twentieth century. In other words, the intervening four hundred years of history colors the writers’ perceptions, creates an ironic distance, grants knowledge of the world and its peoples and its literatures that the original author never could have imagined. Your Quixote will be different from my Quixote, though they might have the exact words in the same order. Like so many of Borges’s stories, it was brilliant—not only was it clever and funny, but it showed how every act of writing is at once both imitation and wholly original, and how imperfect the act of communication is between reader and writer.

As I read and savored the story, I became vaguely aware of a commotion near me. A small crowd had gathered near the window and door of the coffeehouse, and they were buzzing about something. I looked up at the server near me as she craned her head to get a peek out the window closest to me.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“It’s Borges, of course,” she said, as though Borges always came into the Runcible Spoon. Indeed, Borges was walking slowly up the path to the coffeehouse, led carefully by a young woman.

This meeting was not quite the heavy-handed coincidence it might seem at first glance. Yes, I was reading Borges’s work, and yes, he was now walking up the path of the very coffeehouse in which I sat. In itself, this was about as Borgesian a moment as a mere mortal such as myself could ever have, and for that reason, I might think to title this memory, “Borges and I,” except that Borges had already written a story called “Borges and I,” about an older Borges meeting a younger Borges. And I’m not trying to be imitative here, or cute, though I should add that at the time, I was trying to be imitative, if not cute. At the time, I thought of myself as Borges Jr. I wrote stories full of significance, stories in which bizarre things happened. I had no idea why they happened, and no one understood my stories, least of all me, and so in my creative writing classes, students and teachers alike were in awe of me. Thank God, I thought, that writers were never required to explain themselves. Thank God for the subconscious. Even if something seemed utterly without meaning, it might still have significance thanks largely to the subconscious and its gentle but insistent way of conning the conscious.

I could hardly bring myself to breathe. I wondered what I should say to Borges. I should say something, shouldn’t I? But I had no idea what that something should be. I wore a garland of mediocre thoughts.

I knew Borges was coming to Bloomington, Indiana. I had simply forgotten when, and so I was taken by surprise. I’ve always been a bit absent-minded and disorganized, so even though Borges was my literary hero, I had managed to forget the dates of Borges’s visit. My professor, Willis Barnstone, had invited Borges to Indiana University. Borges and Willis were great friends, and Willis a translator of Borges’s poetry. One of the great ironies of Borges’s life was that a man who loved books so much should lose his ability to read them. Over the years, his eyesight worsened to the point of blindness. In 1955, after being appointed the Director of the National Library of Argentina, Borges remarked, “I speak of God’s splendid irony in granting me at once 800,000 books and darkness.” One of the great literary injustices of the twentieth century was the fact that Borges never won the Nobel Prize. Over the years, Borges had offended the Swedish judges with his remarks about politics, especially his support of rightist regimes in South America. Under the leftist Peron regime, he and his family had been persecuted, his sister thrown in jail, an attempt made to bomb his family home, and he had been appointed poultry inspector for the Buenos Aires municipal market.

Borges himself was always sanguine about being overlooked for the Nobel. “Not granting me the Nobel Prize has become a Scandinavian tradition,” Borges remarked once. “Since I was born they have not been granting it to me.” The day after Márquez won the Nobel in 1982, the Boston Globe quoted novelist A. G. Mojtabai at Harvard, “Every year I look in vain for Borges.” She wasn’t the only one. But in a way, it’s a good thing that Borges never won the Nobel Prize. This oversight simply diminishes the Nobel and reminds us that human judgment is fallible and that the only judgment that matters is that of each individual reader judging each individual writer and what the work on the page means at the moment of contact between reader and writer.

The Runcible Spoon was one of those places where strangers sit with one another at the various tables. My table that day was closest to the door, and that’s where Borges and his guide chose to sit, Borges directly across from me. The distance between me and him was perhaps four times (at most) the distance between you and the page you’re reading at this moment. You understand that this was my literary hero, that I was not expecting Borges (of course) to wander into the Runcible Spoon that day, nor did I expect that he would sit across from me. When I saw they were heading my way, I quickly threw my copy of Labyrinths on the floor beside my chair. I don’t know why, but it seemed the thing to do. I felt vaguely embarrassed that I was reading the author who had joined me at the table. And it would have been ridiculous for me to continue reading Borges while Borges sat across from me.

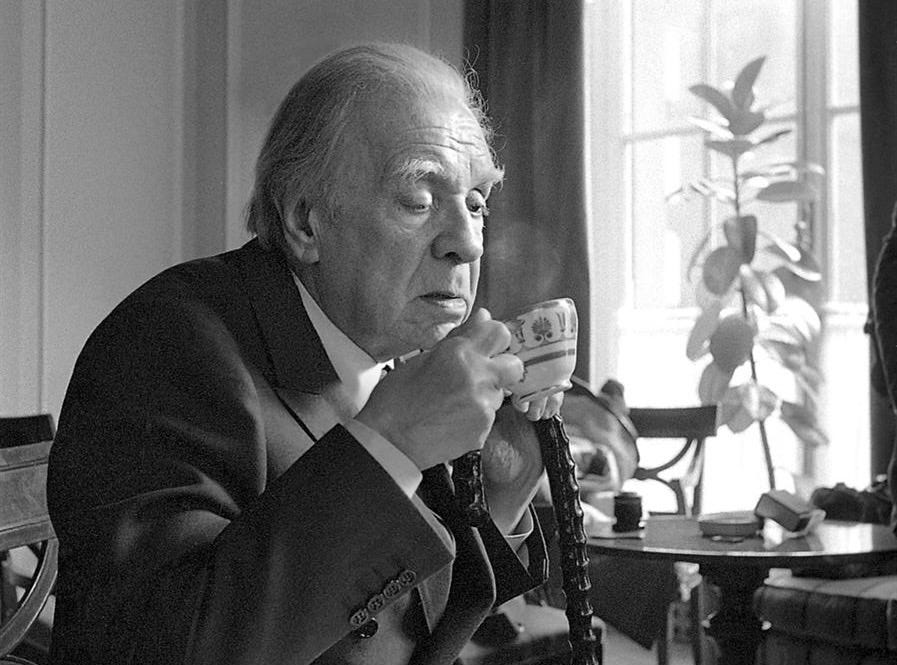

The server took Borges’s order quicker than I’d ever seen her move before, and for the next half hour Borges and his guide chatted amiably over a double espresso with lemon rind (Borges) and a Café au lait (guide). My own coffee cup was empty and remained so, only a cold froth at the bottom and around the rim of the cup. I couldn’t bring myself to order. I could hardly bring myself to breathe. I wondered what I should say to Borges. I should say something, shouldn’t I? But I had no idea what that something should be. I wore a garland of mediocre thoughts. Banal expressions of hero worship tape-looped through my mind. But here was my chance. I could say anything I wanted to Borges if I could only think of what to say, and he would have to acknowledge me. Of course, Borges couldn’t see me, or if he did, I only appeared as a vague dark shape, perhaps a potted plant between the table and the window. If he had seen me, he might have said something, some small polite thing to acknowledge that we were sharing the same table. His companion certainly had no intention of acknowledging me. She was with Borges and he was her Borges and I could see from her posture alone, fiercely straight, that she meant to keep him to herself.

What happened happened. I can’t alter it now, though at the moment, I wished with all my heart that I could rewind the previous thirty minutes and make something different happen. What happened was this: exactly nothing. The graduate student paid the bill and the two of them got up and left and I looked after them as though I were a ghost watching the living live. Should I say how I felt? Should I spell it out? All I can say is that I knew I would never, not in my wildest imaginings, ever have a chance like this again.

As soon as Borges left, the Runcible Spoon returned to normal—that is, the server resumed her aloof stance between the kitchen and the main floor of the coffeehouse, patrons resumed their studies and conversations, and I retrieved Labyrinths off the floor, placed it in my backpack, and drove my moped home.

I know this much. What happened was what should have happened because I’ve come to understand that this is exactly the relationship of the reader to the writer. The writer vaguely perceives the shape of the reader out there. The reader, barely breathing, wishes there was something to say, anything that would decrease the distance between them. And each is there, directly across the table from the other.